The Mystery of Ellen Ternan

Explore Charles Dickens' relationship with the young actress

Forget who killed Edwin Drood, Dickens scholars and amateur enthusiasts have been trying to solve Dickens' last and greatest mystery since his death in 1870. Namely, what exactly was his relationship with Ellen Lawless Ternan?

In the 1850s Dickens had become increasingly dissatisfied with his wife, Catherine. Catherine had borne ten children and had grown quite stout and lethargic. Peter Ackroyd, in his 1990 biography, Dickens, describes Charles' dissatisfaction with Catherine in one word: "Lassitude. In other words, want of ardour. Want of enthusiasm and quickness. Want of all the qualities on which Dickens prided himself" (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 687). A defining event in the deterioration of the Dickens marriage occurred in February 1855 when Dickens received a letter from an old flame, the former Maria Beadnell, now Maria Winter, and a married woman. Dickens and Winter exchanged passionate letters, Dickens apparently laboring under the delusion that, although he had visibly aged, Maria had remained the youthful beauty of old. Dickens finally set up a face-to-face meeting and found that the former beauty had grown old, fat, and ugly. Dickens quickly cooled on Mrs Winter, whom he lampooned as Flora Finching in Little Dorrit (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 724-729).

Dickens met the Ternans, Maria, Fanny, Ellen, and their widowed mother, Frances, during rehearsals for Wilkie Collins' play The Frozen Deep in August 1857. Dickens and his amateur troupe had been performing the play using his daughters in the female roles but when the decision was made to take the play on the road, to Manchester, he decided to hire professional actresses (Tomalin, 1990, p. 72-73).

The forty-five-year-old Dickens became enamored with the youngest of the sisters, eighteen-year-old Ellen, called Nelly. Soon rumors of Dickens’ indiscretions were rampant and he battled them by severing friendships and business relationships with anyone who didn’t see things his way. He also finally separated from Catherine, who was installed in a house in Gloucester Crescent, near Regent's Park, with the oldest son Charley and £600 a year. The rest of the children remained with their father. Catherine's younger sister, Georgina, also remained with Dickens as housekeeper. This situation was soon the cause of additional rumors that Dickens was having an affair with his sister-in-law, considered incest in Victorian times (Slater, 2009, p. 451-453).

In an effort to deflect blame from himself, Dickens gave his tour manager, Arthur Smith, a statement which would later become known as "the violated letter." He instructed Smith to "show it to anyone who wishes to do me right, or to anyone who may have been misled into doing me wrong". Smith apparently showed the letter around and it was published, without Smith's knowledge, in the New York Tribune on August 16, 1858 and then reported throughout England (Johnson, 1952, p. 923-925).

On June 7, 1858 Dickens published a personal statement in The Times which was repeated on the front page of Dickens' weekly magazine Household Words on June 12. Dickens biographer Ralph Strauss called it "the stupidest thing Dickens ever did in his life" (Straus, 1928, p. 250).

Many others agree. How could Dickens, a man of genius so adept at describing, in beautiful language, the human heart in his novels, fail to foresee the flame-fanning results of these ill-conceived epistles? Anyone who had not heard the rumors certainly did now!

On June 9, 1865 Dickens was returning from a vacation in France with Nelly and her mother when they were involved in a serious railway accident at Staplehurst in Kent. Dickens managed to get Nelly and her mother out of the railway carriage as it hung precipitously over the edge of a bridge. Afraid of being discovered, he hustled them off to London on one of the first trains to arrive with medical aid. Ten people were killed and more than 40 injured, Dickens stayed and provided what help and comfort he could (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 958-961). In a letter to his friend Thomas Mitton four days after the accident Dickens would only say that his travelling companions were two ladies; an old one, and a young one (Letters, 1999, v. 11, p. 56-57).

Dickens remained attached to Ellen until his death in 1870. When Dickens' will was published in the press it revealed that he had left Nelly £1000, spurring more controversy. In the years following Dickens’ death damage control was taken up by Georgina, and Dickens’ son Sir Henry Dickens. By 1933 Georgina, Nelly, and all of Dickens’ children were dead and the floodgates seemed to open once more on Dickens' relationship with Nelly.

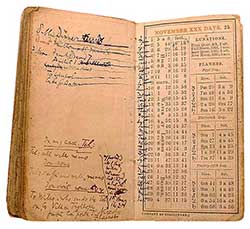

Sleuthing among amateur and professional scholars was aided by the discovery of Dickens’ stolen or lost diary of 1867, which surfaced in 1943, and in which coded entries were examined to disclose information about Nelly. Information was also gleaned through the examination of letters, sometimes with the use of infra-red photography to restore obliterated passages, and the examination of rate books disclosing residences Dickens was paying rents for in and around London, under assumed names. There was speculation about a child (or children) Dickens may have fathered with Nelly (Tomalin, 1990, p. 167-182). Many felt that Dickens' infatuation with Nelly was unrequited and caused him to be unhappy the rest of his life. Many also believe that Dickens' female characters in the later novels were based on Nelly: Lucie Manette from A Tale of Two Cities, Estella from Great Expectations, Bella Wilfer from Our Mutual Friend, and Rosa Bud from The Mystery of Edwin Drood (Slater, 2009, p. 471).

So far, evidence showing that Dickens' relationship with Nelly was anything but platonic remains circumstantial. However, most recent biographers firmly believe that Dickens and Nelly were lovers.

Dickens' legacy of representing family, hearth, and home, remains intact lacking any real proof to the contrary. If any legitimate primary source ever comes to light it would, as Michael Slater notes, quoting Professor Kathryn Hughes, "be like finding out that Father Christmas has been to a brothel" (Slater, 2012, p. 191).

For the fascinating complete story see these books:

The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens by Claire Tomalin (1990)

The Great Charles Dickens Scandal by Michael Slater (2012)

Trailer for the 2013 film version of The Invisible Woman starring Ralph Fiennes and Felicity Jones