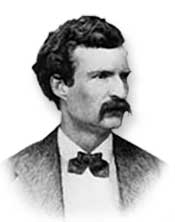

Mark Twain Reviews Charles Dickens

Mark Twain Review of Dickens' Public Reading in New York

I only heard him read once. It was in New York, last week. I had a seat about the middle of Steinway Hall, and that was rather further away from the speaker than was pleasant or profitable.

Mark Twain

Promptly at 8 P.M., unannounced, and without waiting for any stamping or clapping of hands to call him out, a tall, "spry," (if I may say it,) thin-legged old gentleman, gotten up regardless of expense, especially as to shirt-front and diamonds, with a bright red flower in his button-hole, gray beard and moustache, bald head, and with side hair brushed fiercely and tempestuously forward, as if its owner were sweeping down before a gale of wind, the very Dickens came! He did not emerge upon the stage -- that is rather too deliberate a word -- he strode. He strode -- in the most English way and exhibiting the most English general style and appearance -- straight across the broad stage, heedless of everything, unconscious of everybody, turning neither to the right nor the left -- but striding eagerly straight ahead, as if he had seen a girl he knew turn the next corner. He brought up handsomely in the centre and faced the opera glasses. His pictures are hardly handsome, and he, like everybody else, is less handsome than his pictures. That fashion he has of brushing his hair and goatee so resolutely forward gives him a comical Scotch-terrier look about the face, which is rather heightened than otherwise by his portentous dignity and gravity. But that queer old head took on a sort of beauty, bye and bye, and a fascinating interest, as I thought of the wonderful mechanism within it, the complex but exquisitely adjusted machinery that could create men and women, and put the breath of life into them and alter all their ways and actions, elevate them, degrade them, murder them, marry them, conduct them through good and evil, through joy and sorrow, on their long march from the cradle to the grave, and never lose its godship over them, never make a mistake! I almost imagined I could see the wheels and pulleys work. This was Dickens -- Dickens. There was no question about that, and yet it was not right easy to realize it. Somehow this puissant god seemed to be only a man, after all. How the great do tumble from their high pedestals when we see them in common human flesh, and know that they eat pork and cabbage and act like other men.

Mr Dickens had a table to put his book on, and on it he had also a tumbler, a fancy decanter and a small bouquet. Behind him he had a huge red screen -- a bulkhead -- a sounding-board, I took it to be -- and overhead in front was suspended a long board with reflecting lights attached to it, which threw down a glory upon the gentleman, after the fashion in use in the picture-galleries for bringing out the best effects of great paintings. Style! -- There is style about Dickens, and style about all his surroundings.

He read David Copperfield. He is a bad reader, in one sense -- because he does not enunciate his words sharply and distinctly -- he does not cut the syllables cleanly, and therefore many and many of them fell dead before they reached our part of the house. [I say "our" because I am proud to observe that there was a beautiful young lady with me -- a highly respectable young white woman.] I was a good deal disappointed in Mr Dickens' reading -- I will go further and say, a great deal disappointed. The Herald and Tribune critics must have been carried away by their imaginations when they wrote their extravagant praises of it. Mr Dickens' reading is rather monotonous, as a general thing; his voice is husky; his pathos is only the beautiful pathos of his language -- there is no heart, no feeling in it -- it is glittering frostwork; his rich humor cannot fail to tickle an audience into ecstasies save when he reads to himself. And what a bright, intelligent audience he had! He ought to have made them laugh, or cry, or shout, at his own good will or pleasure -- but he did not. They were very much tamer than they should have been.

He pronounced Steerforth "St'yaw-futh." This will suggest to you that he is a little Englishy in his speech. One does not notice it much, however. I took two or three notes on a card; by reference to them I find that Pegotty's anger when he learned the circumstance of Little Emly's disappearance, was "excellent acting -- full of spirit;" also, that Pegotty's account of his search for Emly was "bad;" and that Mrs Micawber's inspired suggestions as to the negotiation of her husband's bills, was "good;" (I mean, of course, that the reading was;) and that Dora the child-wife, and the storm at Yarmouth, where Steerforth perished, were not as good as they might have been. Every passage Mr D. read, with the exception of those I have noted, was rendered with a degree of ability far below what his reading reputation led us to expect. I have given "first impressions." Possibly if I could hear Mr Dickens read a few more times I might find a different style of impressions taking possession of me. But not knowing anything about that, I cannot testify (twainquotes.com).