Three Actors: An Examination of Charles Dickens' Love of Theatre

Mr Macready, Mr Crummles, and Mr Dickens

Being an overview of the theatrical life of Mr Charles Dickens, his Theatrical Friends and his Theatrical Characters.

By Herb Moskovitz

Reprinted with kind permission of the author

Published on this site July 9, 2015

A Boy's Love of Theatre

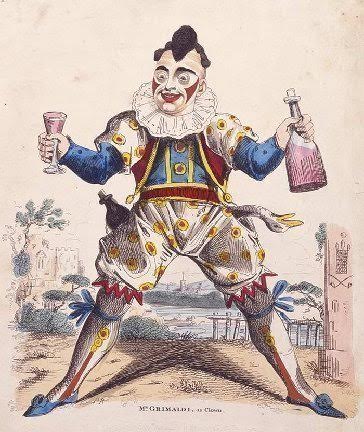

John Dickens loved the theatre. He introduced his children to the wonders of the stage when they were very young. In the years the children were growing up, live theatre could be seen all over England. Probably the first live performance John's son, Charles, saw was a pantomime.

Young Charles saw the great clown Grimaldi when he was about eight years old.

In Rochester, he and his family would see shows at the Theatre Royal. He saw Shakespeare's Richard III and reported that the witches in Macbeth made his heart "leap with terror." Comedies by Goldsmith "brought tears of laughter to his eyes." Goldsmith and Shakespeare remained his favorite playwrights when he was an adult.

These theatres weren’t very good. They were small, dark and dirty, but they brought the magic of theatre into his life forever.

Young Charles had an expressive mobile face and he quickly learned that he could please his family and his father's friends by entertaining them. He would happily perform songs while standing on a chair or table, eager to hear the applause it would bring. He grew up loving the sound of applause.

At home, young Charles would put on a variety of theatrical ventures in the living room: pantomimes, comedies, melodramas, magic-lantern shows, and charades. Charles was an actor, producer, director and a playwright.

He would sing songs such as "The Cat's Meat Man" a comic song that was part of his repertoire for years.

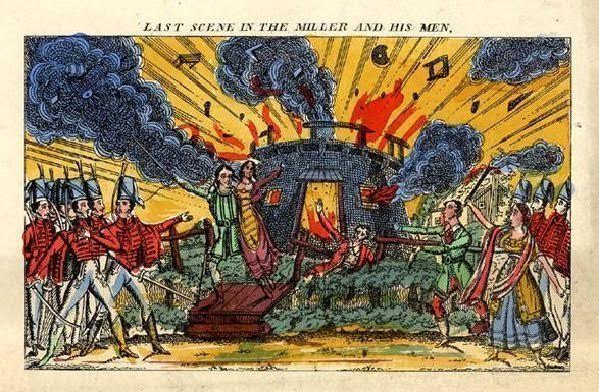

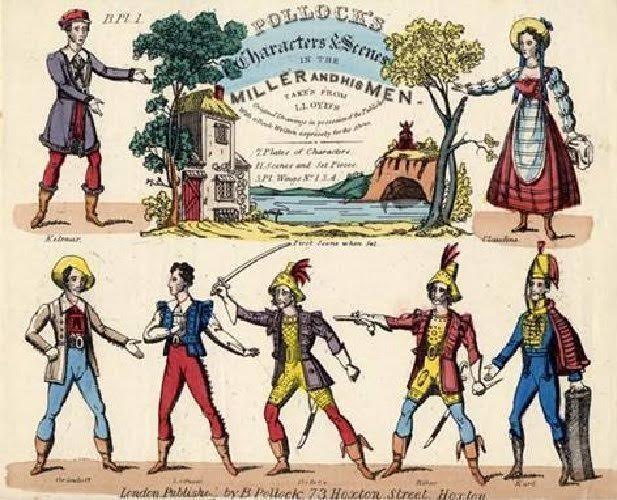

Charles also participated in school theatricals; in such favorites as the melodrama, The Miller and His Men.

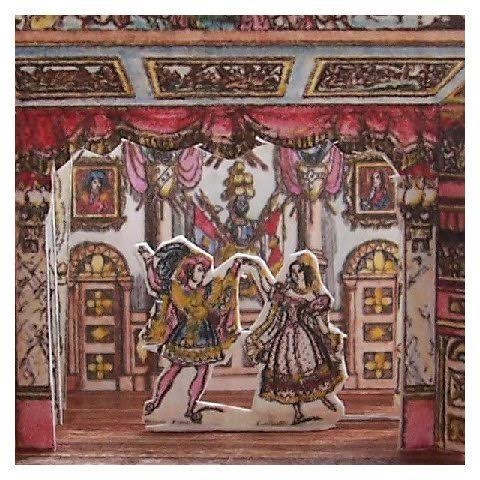

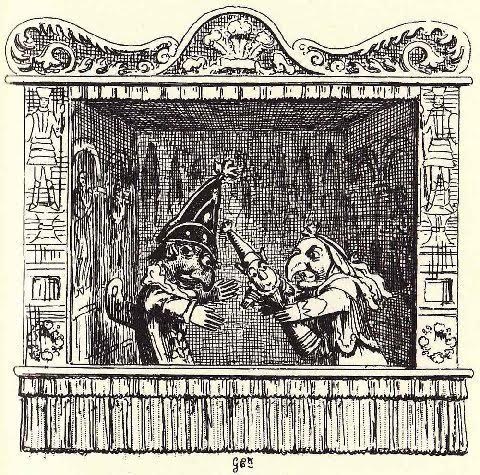

One of his relatives made him a toy theatre. This toy would have allowed him to develop a talent of portraying many characters in the same scene.

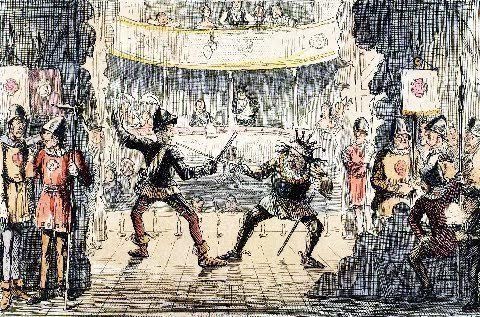

And here we see toy theatre characters ... from The Miller and his Men.

He later wrote about toy theatres in his story, A Christmas Tree.

As he grew up he developed his talents for acting and mimicry. At Wellington House Academy he entertained his fellow clerks, as one of them reported, with imitations of "the low population of the streets of London in all their varieties" and "the popular singers…whether comic or patriotic…He could give us Shakespeare by the ten minutes, and imitate all the leading actors of that time."

In March of 1832, when he was twenty, he recognized his own talents and wrote to George Bartley, the manager of the Covent Garden Theatre, requesting an audition. He gave his age and "exactly what I thought I could do; and that I believed I had a strong perception of character and oddity, and a natural power of reproducing in my own person what I observed in others." Bartley set an appointment for April, and young Charles practiced his repertoire of songs and comic skits. But on the appointed day, he had "a terrible bad cold and an inflammation of the face."

He never again attempted a professional actor's life, but contented himself by becoming a voracious theatergoer.

When he was an office boy at Ellis and Blackmore’s he loved to go to the theatre. Much of it was second rate theatre but he wouldn’t have cared at the time.

But he knew enough to admire good acting. When he was a shorthand writer at Doctors' Commons he went to the theatre nearly every night for at least three years. To quote Dickens, "going to where there was the best acting: and always to see Mathews, whenever he played."

Charles Mathews the Elder

Charles Mathews the Elder was one of Dickens' favorite actors in his youth. Mathews gave solo performances in what he called "At Homes." He would start with a comic lecture; deliver varied monologues as different characters, and sing comic songs throughout the evening. For his finale he presented what he called a "monopolylogue", which was a one-act play in which, by using quick costume changes and exits and entrances, Mathews would play the entire cast of five or six parts. We will see how Dickens borrowed what he saw Mathews do, when he did his own amateur theatricals and public readings.

19th Century Theatre

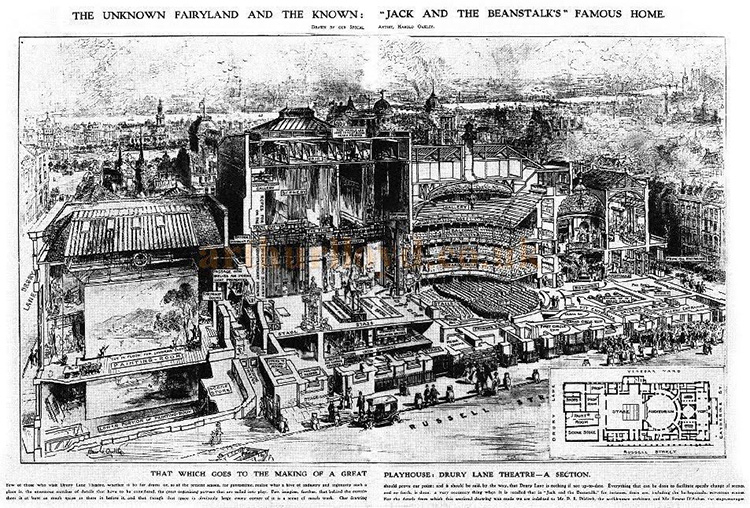

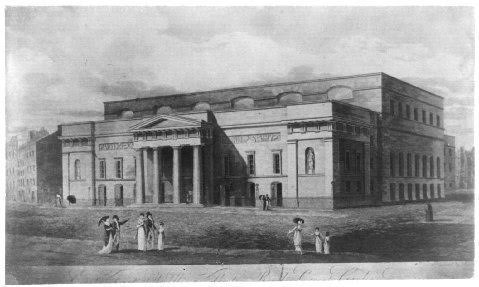

Now, to understand where Charles Dickens fit into the 19th Century theatrical world and vice versa, we will need to take a quick look at British Theatre during the early part of Victoria's reign. As you have seen by reading Nicholas Nickleby, that theatrical world had very little resemblance to our own - it was a "whirl of entertainments." Because of a rather stupid 1737 law called the Theatre Regulation Act, only two theatres were allowed to perform serious drama - The Covent Garden and the Drury Lane. They did what was called "Legitimate Theatre." This was the theatrical world of the most celebrated British actor of his day, William Charles Macready.

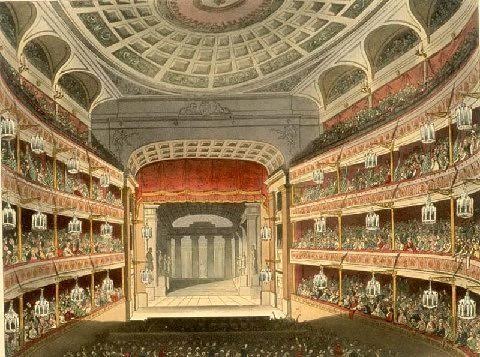

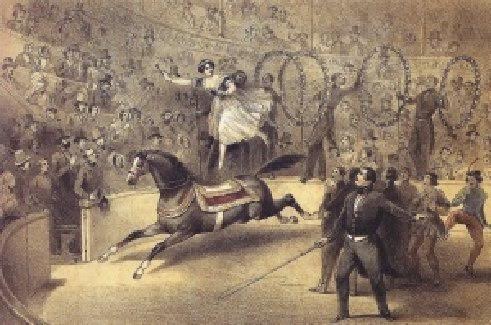

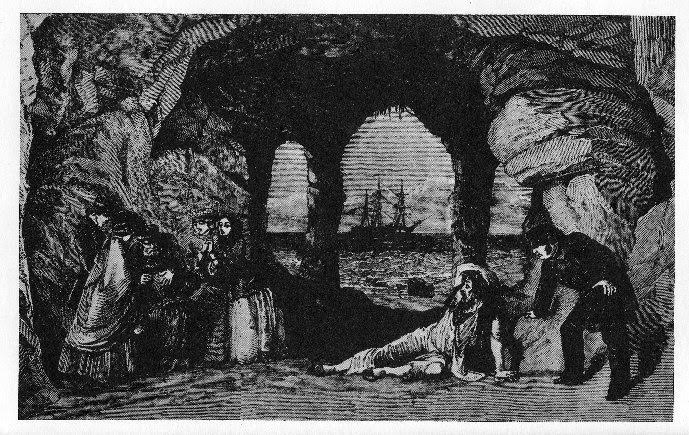

All of the other theatres could not put on plays that relied on spoken dialogue. So the lesser theatres developed alternate entertainments combining music, dance, scenic splendor, pageantry, costuming, acrobatics and equine performances. And they could put them all on in a single long evening.

Actors would put on a show with pantomime or they would be grouped in tableaux. In a tableaux, the actors would stand like waxworks, reproducing on the stage with accurate scenery and costumes, favorite paintings or even Dickens novels...imitating a series of Phiz's illustrations to tell the story.

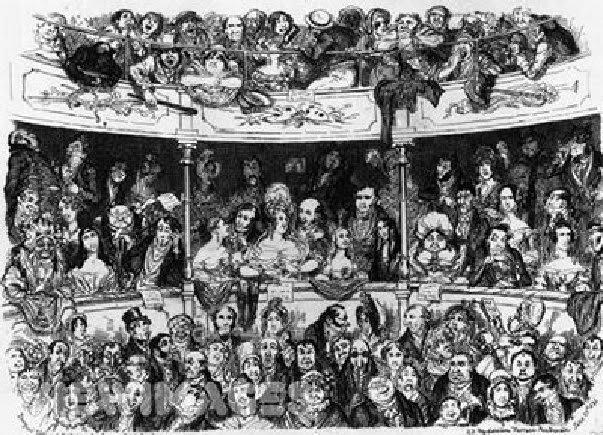

Melodrama was acceptable for the minor illegitimate theatres, since tragedy could only be done by the legitimate. But the dialogue would be a hodgepodge of verse, prose and blank verse. The theatres themselves were usually small and smoky from the flaring limelights. (The limelights also made the theatres dangerous fire hazards)

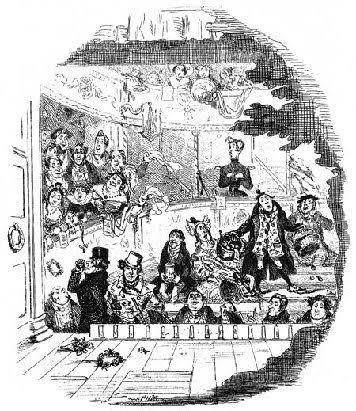

Audiences were rowdy and would throw orange peels at the stage if the acting displeased them. They would also throw pennies…which were quite larger than our own…they would throw pennies at the actors…but with the intention of injuring them, not rewarding them.

This was the theatrical world of Vincent Crummles.

Influence of theatre in Dickens work

Dickens used what he knew of the theatre in much of his works. He wrote several Sketches by Boz that have interesting descriptions of the Victorian theatres that he knew.

There is an extended section on "Astley’s" and another one on "Private Theatres," that offer an interesting view of the theatre of Dickens's youth. One could actually buy a part in a production. The sketch, "Private Theatres" starts out with a price list of parts that could be purchased in Richard III. The larger roles had a higher price: "Richard the Third. - Duke of Glo'ster 2ls.; Earl of Richmond, 1l; Duke of Buckingham, 15s.; Catesby, 12s." And so forth.

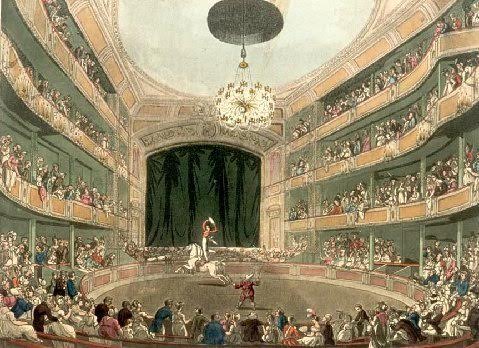

Astley’s Amphitheatre, which was a rather remarkable combination of theatre and circus, was talked about at length in the Sketches. Dickens revisits Astley's in his novels when Mr George goes there in Bleak House and Kit Nubbles and his family attend in Old Curiosity Shop.

Also in Sketches by Boz, Dickens has a hilarious description of amateur theatricals in the sketch, "Mrs Joseph Porter." One of the audience members knows his Shakespeare better than the actors, and has no problem with telling them their mistakes as the show progresses.

Dickens would draw upon the theatre for characters in his novels and stories as well. His first novel, The Pickwick Papers, introduces us to

Alfred Jingle, an itinerant actor who continually embarrasses Pickwick and friends.

Mr Wopsle performs in amateur plays in Great Expectations and other writings bring us an assortment of actors,

Punch and Judy men,

and circus performers. But the most theatrical of all of Dickens's work is Nicholas Nickleby.

Mr Crummles and his troupe of actors are among the most memorable characters introduced in the novel. The novel itself reads like a melodramatic stage play, and indeed is very suitable to being adapted as a play;

as proven by the Royal Shakespeare Company.

The novel was dedicated to the most illustrious actor of Dickens’s time: William Charles Macready.

William Charles Macready

William Charles Macready was the most eminent tragedian of the early nineteenth century after the great romantic actor Edmund Kean died in 1833. Macready was a widely read and cultivated man, but actors of the period were looked down upon, and he loathed his own profession.

He sought to raise the professional style of acting and carefully thought out every action he would take on the stage. He was attempting to uphold the standards of fine drama in a period of decline, and in fact, he pointed the way toward the drawing-room realism of the 19th century.

Macready felt (and Dickens agreed with and defended him) that an actor had a right to challenge an audience's preconceptions.

Because the cultivation of theatrical art was uppermost in his mind, his rehearsal practice was extensive. But nineteenth century actors considered rehearsals a waste of time.

Actress Fanny Kemble recalled, "He was unpopular in the profession, his temper was irritable and his want of consideration of the persons working with him strange in a man of so many fine qualities. His artistic vanity and selfishness were unworthy of a gentleman, and rendered him an object of both dislike and dread to those who were compelled to encounter them."

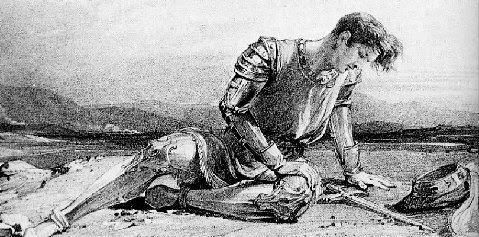

Macready’s greatest success on stage was as Macbeth, but even here other actors shunned him. But with good reason. He would get so wrapped up in his character that it was actually physically dangerous to duel opposite him. His Macbeth may really have been trying to kill Macduff.

If an actor bumped into him onstage, Macready would let out a torrent of oaths. Once when he was lying on stage playing a dead character, another actor accidentally stepped on his hand. The corpse sat up, said, "Beast! Beast of Hell!" then realized where he was and promptly dropped dead again.

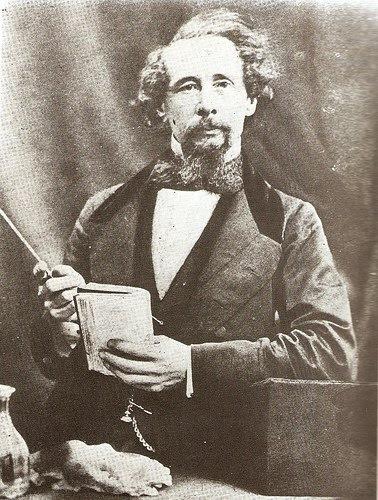

Dickens's lifelong friend, John Forster introduced Macready to Dickens on June 16, 1837, and they became close friends very quickly. Within days of being introduced, they were frequently walking, dining and consulting together.

Dickens told Macready that, as "a mere boy, I was one of your faithful and devoted adherents in the pit," becoming 'more earnest' in his study as he grew older. He wrote enthusiastically about many of Macready's performances, including his 'fresh, distinct, vigorous and enjoyable' Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing.

When Macready was devastated by the loss of his three-year-old daughter in 1840 he noted in his diary, "Received a dear and most affectionate note from Dickens which comforted me as much as I can be comforted."

A few months after that, Macready wrote to Dickens and pleaded with him to spare Little Nell's life. Although Dickens still killed Little Nell off, he enclosed a personal note to Macready along with his copy of Master Humphrey's Clock that contained the death of Nell.

In 1841, Macready may have performed his most critical act of friendship to Dickens. He patched up a serious quarrel between Dickens and Forster. After an escalating argument Dickens ordered Forster out of his house. Macready "spoke to both of them and observed that for an angry instant they were about to destroy a friendship valuable to them both."

When Dickens and his wife, Catherine toured the United States in 1842, it was Macready who watched over the Dickens children. Though it has been reported that the children really didn’t care for the chilly severity of the Macready household.

In 1842 Macready wrote in his diary, that Dickens was "a friend who really loves me." Dickens quarreled with all of his friends but not once, it seems, did he quarrel with Macready. Yet, as we have seen, Macready was a morose egotist with a violent temper. In an ode, Tennyson called him "moral, grave, sublime."

Macready always attended the celebratory dinners that marked the completion of Dickens' novels and he was deeply moved by the high compliment when Dickens dedicated Nicholas Nickleby to him. It may have been more fitting if Dickens had a great actor in the novel instead of Vincent Crummles...but we will let that pass.

Macready was a manager of the Covent Garden Theatre in 1837 to 1839, and it was hoped that he would halt what was perceived as a decline in dramatic art. He mounted new works by contemporary playwrights and staged thirteen major revivals of Shakespeare.

Dickens was a tireless artistic advisor to Macready during this period. Although Macready was most noted for his portrayal of Macbeth it was his production of King Lear that most influenced Dickens' writing. It was Macready's conception of King Lear (in what we would perceive as being more melodramatic than tragic) that helped Dickens in his portrayal of Little Nell and her grandfather in The Old Curiosity Shop.

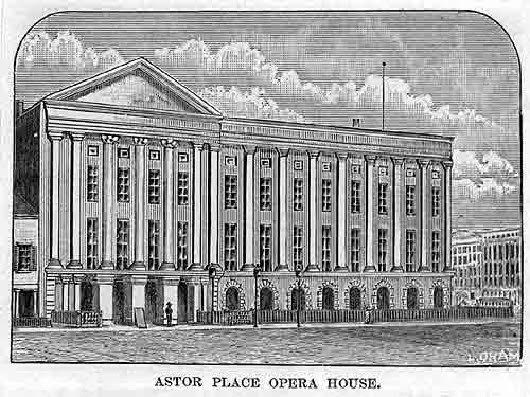

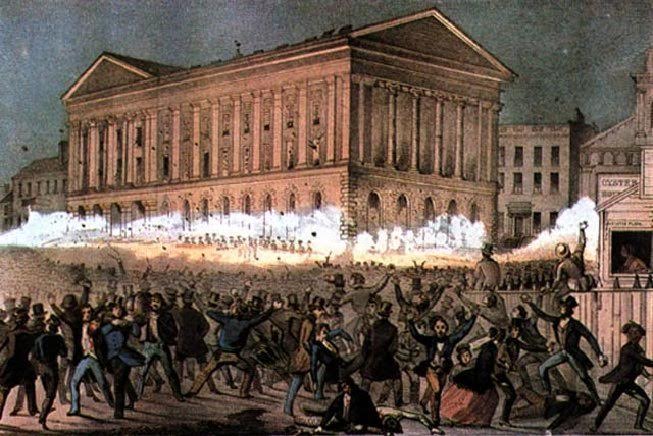

In 1849, Macready was a central figure in a tragic event that illustrates how important theatre was to 19th century audiences. He was appearing as Macbeth at New York’s Astor Place Opera House.

The famous Philadelphian actor, Edwin Forrest, who had a dislike of Macready, mounted a competing production at the Broadway Theatre. Forrest attracted a following of mostly middle class Americans, who thought he championed American values. The upper class members of New York Society were supporting Macready. The animosity between the fans of the two actors would be akin to rival football team fanatics today.

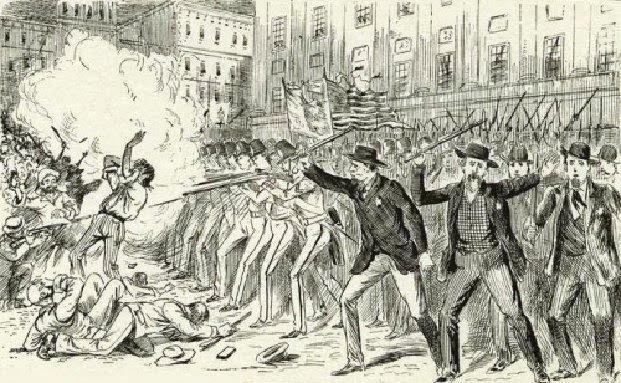

On May 7th the Astor Place Opera House was full of Forrest supporters who ruined Macready's performance by throwing fruits and pennies onto the stage. Things escalated. On May 10, 1849, a crowd of about 10,000 to 15,000 gathered outside the Astor Place Opera House and a few members of the crowd threw paving stones and brickbats through the windows, injuring members of the audience. The police arrived, but when they proved to be ineffective, the state militia was called in. When the crowd attacked the front doors of the theatre, the militia formed a barricade in front of the doors. The mob continued to attack.

A volley of bullets was fired over the head of crowd. They continued the assault. The militia fired into the crowd. Twenty-two people were killed.

Newspapers observed that twice as many Americans had lost their lives in the Astor Place Riot as at the Battle of New Orleans; five times more than died in the Boston Massacre. It was the first time that American troops had ever fired on Americans. New York City, and the nation, were torn apart.

A number of years ago, the Philadelphia Inquirer listed some of the worst moments of the last millennium. The Astor Place Riots made the list.

The friendship lasted until Dickens's death in 1870. At Christmas of 1869 Dickens wrote to Macready, "It needs not Christmas time to bring the thought of you and of our loving and close friendship round to my heart, for it is always there."

Dickens as Playwright

Did you know that Dickens was also a playwright? His first attempt was at age 9 when he wrote Misnar, The Sultan Of India, based on Tales of the Genii.

In 1833 he wrote an operatic Shakespearean satire of Othello which was performed by members of his family.

Dickens loved Shakespeare and there are hundreds of references to the Bard's works in all of his novels, stories, and letters.

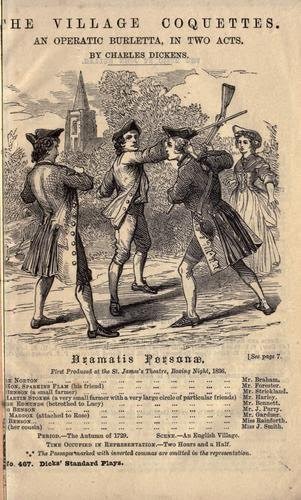

A farce, The Strange Gentleman, was the first Dickens play to be produced on the public stage. It was an afterpiece at the St. James Theatre for an entire season and was published by Chapman and Hall.

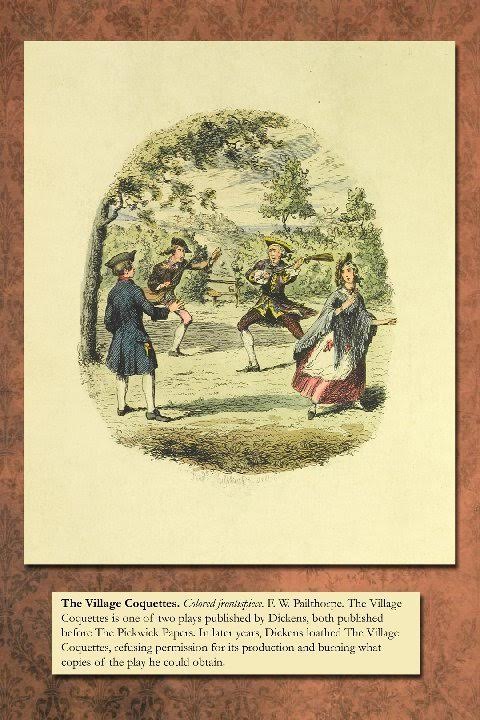

Three years later, he wrote The Village Coquettes, which he claimed would be "the first time that a drama has been united to music, or poetry to songs." However the public didn't like it and it closed with only 16 public performances.

In fact after he became famous, Dickens didn't like it and he wouldn't allow anyone to produce it and if he found a copy of the script he would destroy it.

In 1837, the night Mary Hogarth died, she had attended a farce that Dickens had written. As was typical of the period, there was a short curtain raiser, the main piece and a concluding farce. An evening at the theatre was literally for the entire evening.

One year later, in 1838, Dickens agreed to prepare a little play for Macready, then the manager of Drury Lane Theatre. It was called The Lamplighter, and when completed the author read aloud the "unfortunate little farce" (as he subsequently termed it) in the greenroom of the theatre. Although the play went through rehearsal, it was never presented before an audience, for the actors would not agree about it, and, at Macready's suggestion, Dickens consented to withdraw it, declaring that he had 'no other feeling of disappointment connected with this matter' but that which arose from the failure in attempting to serve his friend.

He had three plays produced and performed before he came to realize he was better as an author of novels.

Although many of his plays survive, they aren't very good and have fallen into obscurity.

But the characters created in his novels certainly did not. And he paints his theatrical characters with loving care and a familiarity that could only have been drawn from his own knowledge of the profession.

Vincent Crummles

Vincent Crummles, the head of the theatrical company in Nicholas Nickleby is referred to by his company as "old bricks and mortar" "because his acting is rather in the heavy and ponderous way."

Crummles is a composite of many actors that Dickens knew…a man dedicated to his profession, with an encyclopedic knowledge of the stage, but with a few human flaws so that he not a romanticized character. His acting company see his flaws but they stay with him since he is the benevolent head of their family.

Perhaps his most serious flaw is his excessive devotion to his daughter, the Infant Phenomenon. One actor-manager, Thomas Donald Davenport is thought to be a likely prototype for Crummles. His daughter, Jean Margaret Davenport, is a likely candidate for the model of the Infant Phenomenon.

The term "Infant Phenomenon" was used widely in the early 19th century to describe child performers. Dickens would no doubt have seen many of them during his days of seeing every show he could. Dickens may have seen Miss Davenport's debut at the Richmond Theatre in 1836. She was performing in Portsmouth (where Nicholas is with the Crummles troupe) shortly before Dickens wrote the chapters introducing the Crummles in Nicholas Nickleby.

Another theatrical character whom Dickens satirized in Nicholas Nickleby is the unscrupulous playwright who stole ideas from Dickens's own novels for theatrical presentation...often before the novel was completed. (This would be a normal occurrence for Dickens stories.) Of course, the playwright would have to guess what ending Dickens intended, and was usually wrong.

Nicholas Nickleby was published between April 1838 and October 1839, yet before 1838 ended, playwrights such as Edward Stirling, wrote and produced plays based on the novel. Not knowing what Dickens intended for his characters, the plays had Ralph trying desperately to kill Smike, or Smike inherits a fortune and lives happily ever after.

Not understanding Dickens's talents of creating believable characters, the evil characters in these plays were nothing but evil, and the good characters were impossibly good. Nicholas in the plays was impossibly sweet.

As a response Dickens created

"Mr Snittle Timberry...(who) was a literary gentleman…who had dramatised in his time two hundred and forty-seven novels as fast as they had come out - some of them faster than they had come out-"

Other dramatizations of his novels were done with Dickens's blessings. And, of course, many new theatrical and cinematic versions continue to be produced today.

Dickens as Actor-Manager

Acting

There is no documentation about young Dickens appearing on stage but as his own sketch about "Private Theatres" tells us, members of the public could pay to be on stage in the small private theatres of his youth. It is highly likely that he did this.

The first performance by Dickens, of which we have any knowledge, was in an amateur theatrical in Montreal in 1842. After that, he became heavily involved in more amateur theatricals. As he had in the past with his family, he now organized his friends, and once again took complete control. Dickens would act as the director, assigning parts and organizing the rehearsals; write the prologues, and supervise the scenery, costumes and lighting.

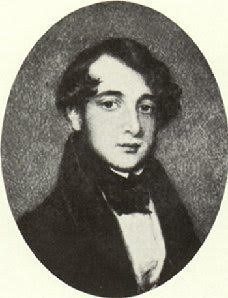

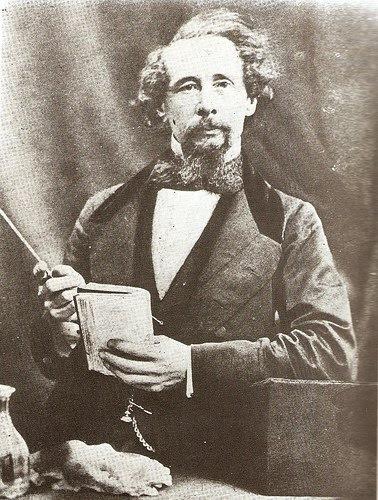

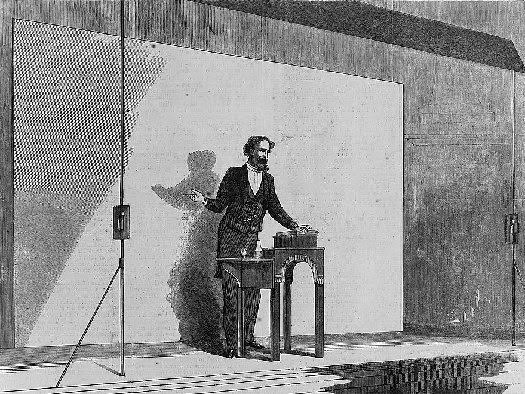

Above we see Dickens at age 35 in a role in a play, "Used Up" cowritten by Charles Mathews.

Macready coached Dickens in his amateur theatricals. He considered Dickens a worthy actor. In fact, though he was contemptuous of non-professional acting he said that Dickens was one of only two amateurs with any pretension to theatrical talent.

Directing

Dickens came close to emulating his professional friend when he put on his amateur theatricals. But he managed to keep his company’s respect and, no doubt, love.

Dickens wrote to Forster, "Everybody was told they would have to submit to the most iron despotism, and didn’t I come Macready over them? Oh no. By no means. Certainly not. The pains I have taken with them, and the perspiration I have expended, during the last ten days, exceed in amount anything you can imagine. I had regular plots of the scenery made out, and lists of the properties wanted; and had them nailed up by the prompter’s chair. Every letter that was to be delivered, was written, every piece of money that had to be given, provided; and not a single thing lost sight of. I prompted, myself, when I was not on...The bedroom scene in the interlude was well furnished … with a ‘practicable’ fireplace blazing away like mad, and everything in a con-cat-e-nation accordingly."

Queen Victoria herself saw Dickens perform six different characters in a charity performance of a farce he had written, "Mr Nightingale’s Diary." It was reported that he was "hilariously credible whether camouflaged as a crusty naval officer, a whining hypochondriac, an old peasant woman or whoever."

Dickens played Captain Bobadil in Ben Jonson's Every Man in His Humour to great acclaim in 1847. One reviewer wrote, "Dickens was glorious. He literally floated in brag-ga-do-ci-o. His air of supreme conceit and frothy pomp in the earlier scenes came out with prodigious force in contrast with the subsequent humiliation which I never saw so thoroughly expressed before. It was a capital conception and acted to its height."

The poet Leigh Hunt said of Dickens’s performance as Bobadil, that it had "a spirit of intelligent apprehension beyond everything the existing stage has known." John Forster noted that Dickens flung himself into that and every other role with the same "passionate fullness" he brought to his writing. Forster went on to say that Dickens continued behaving like Ben Jonson's swaggering loudmouth even when he was off the stage and out of his costume. Shades of Daniel Day Lewis.

Poets, playwrights, famous actors...all lauded Dickens’s acting, but my favorite recorded compliment was from the master carpenter at one amateur production: "Ah, sir, it’s a universal observation in the profession, sir, that it was a great loss to the public when you took to writing books."

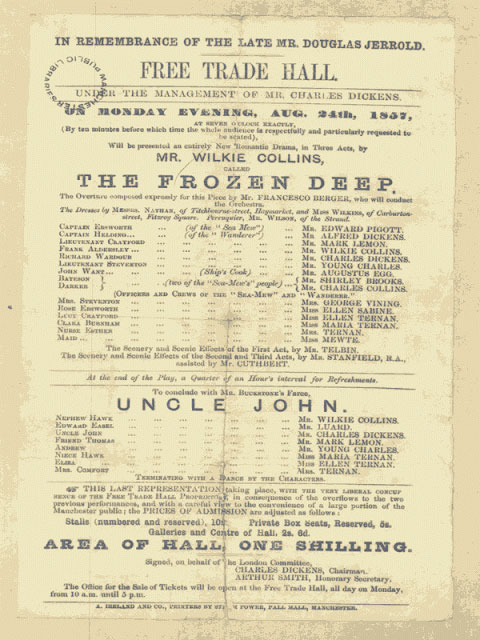

A role in Wilkie Collins's play The Frozen Deep led to two major events in Dickens's life.

Dickens played a man who gave up his own life so that the woman he loved could find true happiness – with another man – the man she loved. This plot twist gave Dickens the idea for his next book, A Tale of Two Cities.

The second important event was that Dickens fell in love with a young actress in the cast. Ellen Ternan, became "the invisible woman," in his life. Their love affair was the subject of a 2013 movie directed by Ralph Fiennes.

His amateur theatrical acting led eventually to Dickens' professional acting career – the public readings.

Public Readings

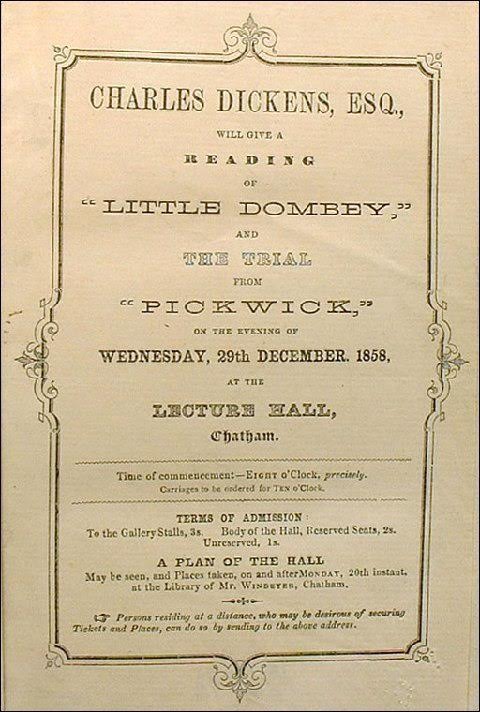

Dickens supported many charities, and in 1853 was asked to give public readings of A Christmas Carol and Cricket on the Hearth on behalf of the Working Men's Institute.

On December 30, 1853 he read at the Birmingham Town Hall. He had ordered the tickets to be priced low so that poor people could afford them. Over 2,000 "working people" gave him a standing ovation when he appeared. He said, "My good friends..."

They stood and applauded again. "I have always wished to have the great pleasure of meeting face to face at this Christmastime."

The readings went very well and for the next few years he would frequently read selections from his novels to an audience for the benefit of various charities. With a large family to support, and the purchase of Gad’s Hill Place to consider, he came up with a groundbreaking idea.

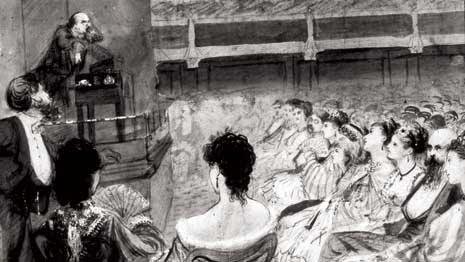

Dickens was the first author to go on the public stage reading his works for money. Even the idea of a public appearance as a marketing strategy was unknown at the time. After one of the first readings, the London Illustrated Times said, "Mr Dickens has invented a new medium for amusing an English audience, and merits the gratitude of an intelligent public."

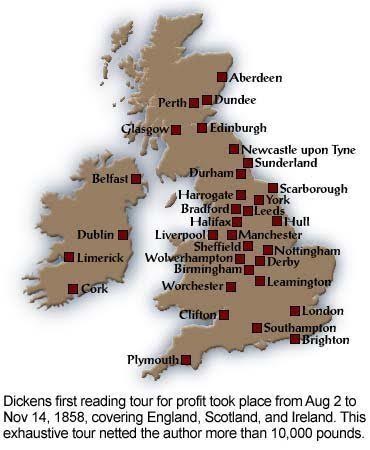

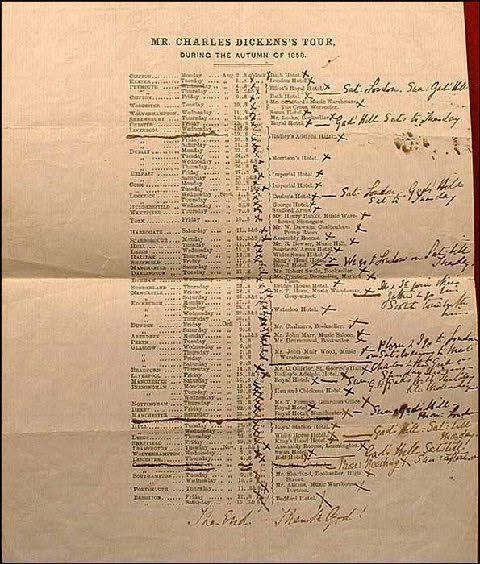

In 1858 he started a reading tour that took him all over England, as well as Scotland and Ireland.

But Dickens didn’t merely read from his works. He acted them!

With his considerable talent and acting experience he was a smashing success. Borrowing what he had seen of Charles Mathews the Elder, he was able to create theatrical scenes with many characters, but with himself as the only one actor.

He was a born actor. Contemporary accounts emphasize his expressive eyes and his gift for gesture. "He rubs and pats his hands," reported one observer, "he flourishes all his fingers, he shakes them, he points them, he makes them equal to a whole stage company in the performance of the parts."

Thomas Carlyle, after seeing Dickens in a performance in 1863 said, "Charley, you carry a whole company of actors under your hat."

His intense concentration in acting gave him a strong, almost a hypnotic power over his audiences when he gave public readings from his works.

What were these evenings like? By all accounts the readings were something to behold. Let us look at some comments by some of his contemporaries who were fortunate enough to see him. Mark Twain writes...

"Mr Dickens read scenes from his printed books. From my distance he was a small and slender figure, rather fancifully dressed, and striking and picturesque in appearance. He wore a black velvet coat with a large and glaring red flower in the buttonhole. He stood under a red upholstered shed behind whose slant was a row of strong lights -- just such an arrangement as artists use to concentrate a strong light upon a great picture. Dickens's audience sat in a pleasant twilight, while he performed in the powerful light cast upon him from the concealed lamps. He read with great force and animation, in the lively passages, and with stirring effect. It will be understood that he did not merely read but also acted. His reading of the storm scene in which Steerforth lost his life was so vivid and so full of energetic action that his house was carried off its feet, so to speak."

An other report tells us that "All his acting talents were brilliantly employed as he alone, in evening dress, standing at a reading table, peopled the stage with different characters, different voices, different mannerisms. His fingers drummed on the desk as he described dancers at a ball; his face contracted into the mean, pinched sneer of Scrooge, and expanded again into the complacent beaming moon of a London alderman; his voice wheezed the ginny snuffle of Mrs Gamp or rose to a convincing falsetto for little Paul Dombey."

Dickens came to the United States in 1868 for a reading tour. He gave 82 readings in the states and earned 20,000 pounds.

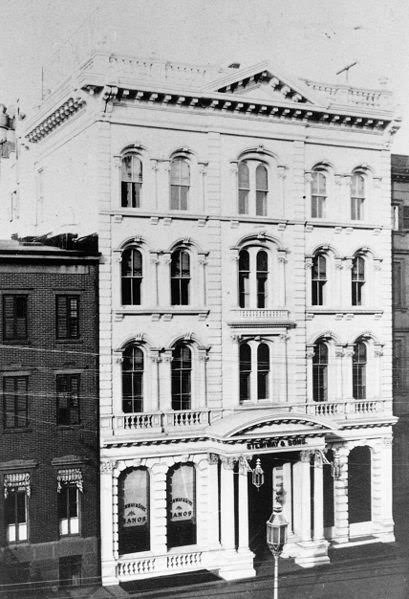

Between December 9, 1867 and April 20, 1868, he gave 22 readings at New York City's first Steinway Hall at 71 East 14th and four readings between January 16, 1868 and January 21 at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn.

In January and February he appeared in Philadelphia at The Concert Hall at 1217 Chestnut Street. This building was fifty feet wide, had a stone block facing and three high arched windows in the front.

Tickets were $2 each. Philadelphia acted much the same way that it acts today when tickets for an important rock concert go on sale. The night before the tickets were to be sold, 50 people were camped out on the sidewalk in the 18-degree cold, securely established with mattresses, blankets and whisky.

The first six readings were sold out in four hours. Hundreds of people were disappointed and scalpers, who managed to get their hands on tickets, resold them at exorbitant prices. The Concert Hall could only hold 1,400. (I wonder why they didn’t use the Academy of Music, which has twice as many (2,897) seats.)

During all his Philadelphia readings Dickens had what he called an "intolerable cold." But his audiences did not suspect anything was amiss. Indeed, The Evening Bulletin of February 14 noted that "Mr Dickens was evidently in the best of humors." Little did they know that Dickens worked his pulse up to 124 most nights, so intense were his readings.

The stage setting was simple and had been designed by Dickens himself. A maroon screen ran along the back extending to the wings. A carpet was on the floor to assist with the acoustics. Above Dickens's head was a row of gas jets which illuminated him and his books, but which were screened so that they threw no glare into the audience's eyes.

A reading desk, about two feet by three feet and three feet high held his books, a pitcher of water and a glass.

Illuminated by the bright lights, framed and thrown into relief by the dark backdrop, and obstructed little by the table and its appointments, he could register on the audience every movement in all his body. The Inquirer of January 14 called the arrangement, "a model of convenience and a gem of invention."

At 8:00 sharp, Dickens would walk onto the stage, without any announcement. He carried the books quickly to his reading desk, put the books down, bowed, smiled and waited for the applause to stop. It was a long wait. He wanted to begin, but the normally reserved Philadelphians lauded him with cheer after cheer and roar after roar. When at last the audience had shown their approval, he would pick up a book, open it, look at the audience and say, "Ladies and gentlemen, I am happy to have the honor of reading to you tonight," name the work and begin reading.

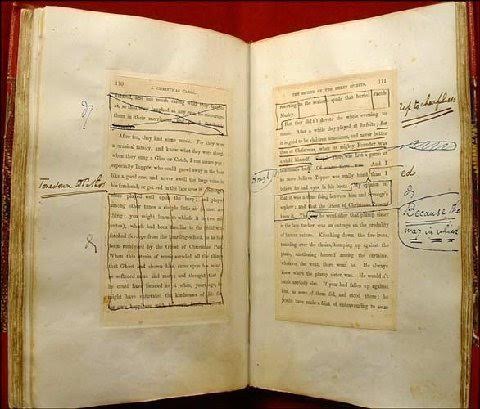

The books were printed copies of his own works, adapted with pen and pencil markings and heavily annotated. This is his reading copy of A Christmas Carol, now in the New York Public Library.

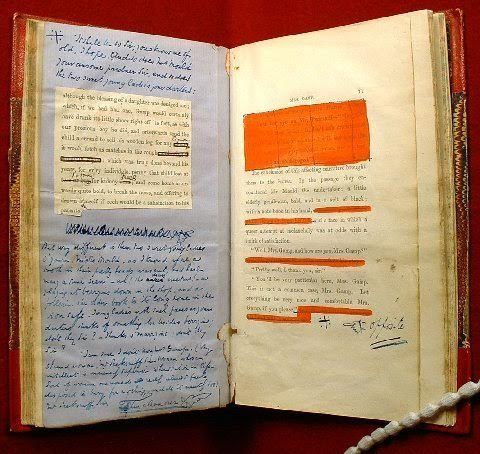

And a copy of Martin Chuzzlewit.

The audiences, expecting a lengthy introduction, overtures and pomp and flourishes were at first taken aback, but very quickly Dickens vanished from the stage and his characters took his place. One moment he would be gruff old Scrooge, and the next he would be timid Bob Cratchit, then hearty, good-natured Fred. His years of theatrical training, from the toy theatre of his childhood, through the amateur theatricals, were paying off.

Most expressive were his eyes and his hands. Especially his eyes. The Press of January 24 admired "his eyes, wonderful eyes they are," that – as the story and the character demand-droop, gleam, shine, blaze, and glare. Performing mostly from memory, Dickens seldom referred to his text and his eloquent eyes were continually on the audience.

When reading A Christmas Carol, he used his hands and his eyes to describe the dancing at Fezziwig’s ball, and put his whole self into the mashing of the potatoes, the sweetening of the apple sauce, and the dusting of the plates-as if he were there and taking part.

The Evening Telegraph reported that when Buzfuz cried, "Call Sam Weller" that Dickens had to stop "for some minutes, so deafening was the welcome."

For his reading from Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens did not enlist that worthy actor, Vincent Crummles, but instead chose the high-spirited encounter with John Browdie, the pathos of Smike and the scene that ended with Nicholas thrashing Squeers, with, as one reviewer commented, "startling reality."

At the end of the evening, Dickens did not take a curtain call.

In the summer of 1868, Dickens's son, Charley, was in the library at Gad’s Hill when he heard what sounded like a tramp beating his wife outside. Charley rushed outside to save the poor woman from her husband, only to find his father creating a reading of the murder of Nancy by Bill Sikes. Dickens was crying out in the woman’s voice and responding with the murderer's. Dickens asked his son what he thought of it. Charley responded, "The finest thing I have ever heard, but don’t do it" Charley saw how much his father was throwing himself into the roles and feared he might further injure his health.

When Dickens added "The Murder" to his readings for the farewell tour of 1869, a critic for The Times wrote, "He has always trembled on the boundary line that separates the reader from the actor, now he clears it by a leap."

Dickens made far more money doing the readings (about 45,000 pounds), than all of his books combined. And of course, the readings made the public go out and buy more of the books. But I think what was even more important to Dickens than the money was the applause.

He once said of audiences: "There’s nothing in the world equal to seeing the house rise at you, one sea of delightful faces, one hurrah of applause!"

Dickens received lots of praise, standing ovations and good notices but the one that probably meant the most to him was in 1869, when Macready, who had just seen him do a public reading of Sikes and Nancy, said

"In my-er-best times-er-you remember them my dear boy-er-gone, gone…it comes to this –er-TWO MACBETHS!"

Dickens used all of his acting talents in the readings. But at a cost. After each Sikes and Nancy reading he would collapse onto a sofa, totally drained, and be unable to speak for some time. His son, Charley is not the only one who believed that the readings contributed heavily to his early death.

Finally admitting his failing health, Dickens scheduled a series of final readings.

The Final Performance

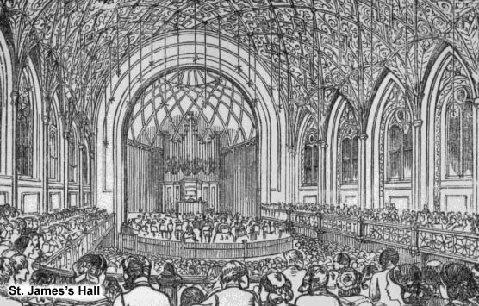

The last one was held on March 15, 1870, at St. James Hall. He read from Christmas Carol and the "Trial from Pickwick" and although he was tired and in pain, he read with verve and brilliance.

After Dickens finished his readings he addressed the audience, "I have enjoyed an amount of artistic delight and instruction which perhaps it is given few men to know; from these garish lights I vanish now for evermore, with a heartfelt, grateful, respectful, and affectionate farewell."

He walked off the stage very slowly. Thunderous applause brought him back. With tears streaming down his face, he kissed his hand to his friends, and then left the stage forever.

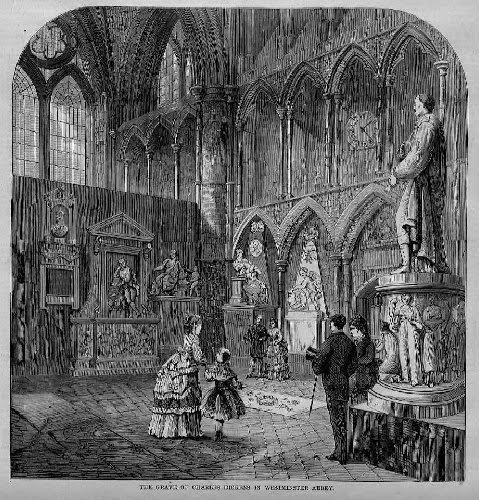

Three months later, the statement, "From these garish lights I vanish now for evermore." was inscribed on his funeral card distributed at Westminster Abbey.

A fitting final scene for a man who loved anything and everything about the theater.

Towards the end of his life, Dickens said to a friend that notion of an ideal existence would have been, not a novelist, but as the manager of a great theater, with a wonderful company and he should have absolute control of it, decide what would be put on and how it was staged and everything to do with sets, lights and costumes.

The theater genes have been passed down to his family. Many current members of the Dickens family act and do public readings.

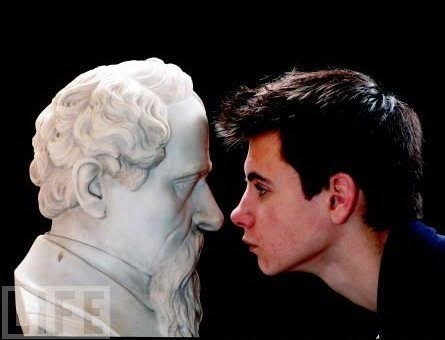

Most notable are great-great-grandson, Gerald Dickens, who often appears in the United States doing public readings, especially of A Christmas Carol...

And great-great-great-grandson Harry Lloyd is a professional actor who appeared recently in Robin Hood, Doctor Who, Game of Thrones, Iron Lady, The Hollow Crown, The Fear and Wolf Hall.

Harry has had two roles in television series adaptations of the Inimitable's works: twelve years ago as young Steerforth in David Copperfield

and a few years ago as Herbert Pocket in Great Expectations.

His great-great-great-grandfather would be so proud.