Charles Dickens - Gads Hill Place

Learn more about Charles Dickens' 'little Kentish freehold'

The Queer Small Boy

I took him up in a moment, and we went on. Presently, the very queer small boy says, 'This is Gads-hill we are coming to, where Falstaff went out to rob those travellers, and ran away.'

'You know something about Falstaff, eh?' said I.

'All about him,' said the very queer small boy. 'I am old (I am nine), and I read all sorts of books. But DO let us stop at the top of the hill, and look at the house there, if you please!'

'You admire that house?' said I.

'Bless you, sir,' said the very queer small boy, 'when I was not more than half as old as nine, it used to be a treat for me to be brought to look at it. And now, I am nine, I come by myself to look at it. And ever since I can recollect, my father, seeing me so fond of it, has often said to me, "If you were to be very persevering and were to work hard, you might some day come to live in it." Though that's impossible!' said the very queer small boy, drawing a low breath, and now staring at the house out of window with all his might.

I was rather amazed to be told this by the very queer small boy; for that house happens to be MY house, and I have reason to believe that what he said was true (Uncommercial Traveller, p. 61-62).

The Shakespeare Connection

Gads Hill was the location of the robbery of wealthy travellers by Sir John Falstaff and Prince Hal, the Prince of Wales and future Henry V, in William Shakespeare's play Henry IV. Charles Dickens loved the Shakespeare association with the place (Hughes, 1891, p. 98-99). The Sir John Falstaff Inn, across the Gravesend Road from Gads Hill Place, was described by Dickens as "a delightfully old-fashioned roadside inn of the coaching days...which no man possessed of a penny was ever able to pass in warm weather." Dickens was a frequent customer at the inn, using it to supply rooms for visitors when Gads Hill was overflowing, and to supply refreshment for events he hosted (Watts, 1989, p. 15-16).

Charles Dickens at Gads Hill

Charles Dickens' purchase of Gads Hill

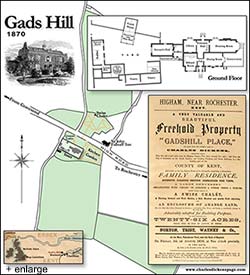

Gads Hill Place was built in 1780 by Thomas Stephens, a former mayor of Rochester (Watts, 1989, p. 16). Dickens learned that the stately mansion he had been fascinated with in his youth, was for sale during a conversation with his friend and associate William Henry Wills (1810-1880) at the offices of his weekly magazine Household Words. The present owner, Eliza Lynn Linton (1822-1898), had inherited the house from her father, Reverend James Lynn, who purchased the property when he was curate of nearby Strood. Eliza Lynn Linton was a celebrity in her own right being the first salaried female journalist in Britain and a regular contributor to Household Words.

Dickens began a protracted negotiation for the purchase in late 1855 and finally bought the house for £1790 in March of 1856 (Johnson, 1952, p. 869-870). Initially, Dickens planned the purchase as an investment but after the separation from his wife, Catherine, and the sale of the London residence, Tavistock House, he moved to Gads Hill permanently. He immediately set about making changes and improvements (Johnson, 1952, p. 961-962).

Bonfire at Gads Hill

Dickens felt that the personal correspondence of public men was being misused in the press to slander and defame. He was going through a particularly ugly separation from his wife, Catherine, at the time and the privacy of his correspondence was particularly important. So on September 3, 1860, shortly after moving into Gads Hill, he built a fire in the field behind the house and incinerated basket after basket of letters he had received over the last 20 years commenting, "Would to God that every letter I had ever written was on that pile." He continued to destroy all correspondence for the rest of his life (Watts, 1989, p. 72-74). Recipients of his letters tended to keep them and over 14,000 such letters exist today (Hartley, 2012, p. viii); however, letters written to Dickens that are still in existence (2019) number little more than 250 (Wikipedia).

Dickens Describes Gads Hill

In July 1858 Charles Dickens, in a letter to M de Cerjat, a friend Dickens had met in Lausanne, Switzerland, wrote: At this present moment I am on my little Kentish freehold (not in topboots, and not particularly prejudiced that I know of), looking on as pretty a view out of my study window as you will find in a long day's English ride. My little place is a grave red brick house (time of George the First, I suppose), which I have added to and stuck bits upon in all manner of ways, so that it is as pleasantly irregular, and as violently opposed to all architectural ideas, as the most hopeful man could possibly desire. It is on the summit of Gads Hill. The robbery was committed before the door, on the man with the treasure, and Falstaff ran away from the identical spot of ground now covered by the room in which I write. A little rustic alehouse, called The Sir John Falstaff, is over the way—has been over the way, ever since, in honour of the event. Cobham woods and Park are behind the house; the distant Thames in front; the Medway, with Rochester, and its old castle and cathedral, on one side (Shore, 1909, p. 265).

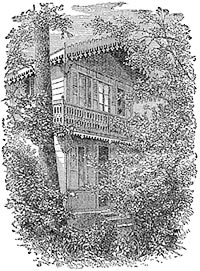

The Swiss Chalet

For Christmas, 1864, Dickens received a gift by rail at the Higham railway station from his friend Charles Fechter, the French actor; a miniature Swiss châlet in 94 pieces, packed into 58 boxes that Forster described as "fitting like the joints of a puzzle" (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 262). At first family and friends gathered for the holidays tried to assemble it, but the construction proved more than they could handle so carpenters were brought in. The property Dickens owned included a wooded area across the Gravesend Road from Gads Hill that he referred to as "The Wilderness" (Watts, 1989, p. 32). Here, on a brick foundation, Dickens had the châlet erected. A tunnel was dug under the road from his front lawn to the wooded area for easy access to the châlet (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 955-956).

During the summer months Dickens used the châlet to write. In a letter to a friend he described this treetop study: "I have put five mirrors in the châlet where I write, and they reflect and refract, in all kinds of ways, the leaves that are quivering at the windows, and the great fields of waving corn, and the sail-dotted river. My room is up among the branches of the trees; and the birds and the butterflies fly in and out, and the green branches shoot in at the open windows, and the lights and shadows of the clouds come and go with the rest of the company. The scent of the flowers, and indeed of everything that is growing for miles and miles, is most delicious" (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 262-264)

The Death of Charles Dickens

Gads Hill from the Auctioneer's Catalogue 1870

Dickens rose early, as was his custom, on a glorious morning on June 8, 1870, at Gads Hill. He spent the morning in the châlet working on The Mystery of Edwin Drood. The story had taken possession of him and the writing came easily, so much so that after lunch he went back to the châlet to write, which was unusual for him. He came back to the house for dinner, and while waiting for the dinner hour, wrote some letters. During dinner, attended only by Georgina, his devoted sister-in-law, she noted that his expression was odd and his face gray. He told her he had been ill for the last hour but that he wanted dinner to continue. A few minutes later he slumped to the floor unconscious. A doctor from Rochester was called, telegrams were sent, and friends and family gathered to watch and wait, but Dickens never regained consciousness. His breathing stopped the next evening, June 9, 1870 (Johnson, 1952, p. 1153-1154).

Charles Dickens had written some of the best of his works, including A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations, at Gads Hill. He was laid to rest at Westminster Abbey in a private ceremony on June 14. The grave was left open for several days while thousands came to pay their respects to England's greatest novelist (Johnson, 1952, p. 1156-1157).