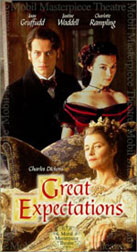

Great Expectations

Dramatized by Tony Marchant: BBC-2, 12-13 April 1999

Review by Robert Giddings

Used with permission from the author

Published on this site March 9, 2002

In translating classical novels into modern television, there are losses as well as gains. Some are understandable, others less so But Middlemarch notwithstanding, after BBC-2's recent attempts at high Victorians-Hard Times (wretched) and Vanity Fair (patchy) -- my expectations were modest. So it was nice to be surprised, if not actually by joy, at least with some pleasure.

In translating classical novels into modern television, there are losses as well as gains. Some are understandable, others less so But Middlemarch notwithstanding, after BBC-2's recent attempts at high Victorians-Hard Times (wretched) and Vanity Fair (patchy) -- my expectations were modest. So it was nice to be surprised, if not actually by joy, at least with some pleasure.

First person narrative was not used. We saw the story as events unfolded. What we lost was the fact that Pip's confusions are the result of the distortions through which he perceives the world. It's quite a trick to get viewers similarly confused. We have got to misunderstand the evidence, just as Pip does. Were we credibly led to believe the legacy was Miss Havisham's? We were really so insensitive as to think that having lost Estelle, we could pop Biddy the question? Were we so insensitive we wanted to chuck Magwitch out the minute he showed up again? Were we really so myopic that we couldn't see Joe's love for Pip had no bounds?

It looked good. The director of photography, David Odd, and production designer, Alice Normington, created a fine washed out quality for the rural Kent exteriors (actually Norfolk), and bustling sense of London and used well selected bits of Edinburgh for the more tenebrous aspects of the metropolis. The bleakness of the marsh country was further driven home by recurring images of circling flights of dreary ducks and melancholy Peter Grimesian music( by Peter Salem). Although Dickens located it earlier in the century, they went firmly for a mid-century look, and several names came to mind-Ford Madox Brown, William Holman Hunt, William Powell Frith among them. These elements were symptomatic of assumptions at the heart of this production. The cover of Radio Times proclaimed that BBC-2 was to deliver "a darkly different Dickens". Saying goodbye to the "tea time classics of yesteryear"-that sausage-factory production line of shallow schedule-fillers-in itself might be no bad thing. Their website made it clear that any version of this masterpiece inevitably emerged in the shadow of David Lean, yet, Lean was the product of a very different age "with very different attitudes". So the producer, (David Snodin) writer (Tony Marchant) and director (Julian Jarrold) sought to make this version for the close of the century "darker and much less sentimental, reflecting the huge changes in values and beliefs which have taken place since 1946...." Well, yes, this may sound desirable and certainly politically correct. But is it sensible? What would life be like devoid of sentiment, I wonder? Sentiment is one of the comforts of life, which frequently works to good purpose and keeps other less desirable, more competitive and destructive qualities in check. Art doesn't just reflect life. It is supposed to examine, evaluate, criticise and ridicule it, so we aspire to be better than we are.

The distortions of this production have strong roots elsewhere. The BBC also told us the Dickens was "almost as much a journalist as novelist" and consequently we should recognise that his works were not "all solely dreamed up" but "based firmly on real people, real events and real places". These assertions are Grandgrindian, but it meant the vitality of the larger than life was missing. Real life or real places or what -- it doesn't matter where these things come from. It is what Dickens creatively does with them that is important, and how he makes them work on our imaginations and our feelings. Remember, fact is stranger than fiction, but fiction is truer. The comic element was almost totally removed. (Wot, no larks?). So, no fun with bread and butter at the table, no Trabbs's Boy, no Joe in London, no Wopsle's Hamlet.

It was the ladies' show, really. Mrs Joe (Lesley Sharp) was magnificent, generous in her animosity, a simmering bomb ever ready to explode. And for once, we began to understand what a bum hand life had dealt her. Miss Havisham, (Charlotte Rampling) although resembling Dickens's description of her but slightly, was utterly convincing as a once beautiful young woman miraculously preserved, albeit fading fast, in a state of gradual senility. Estelle (Justine Waddell) projected in exactly the right proportions qualities of sexual magnetism and emotional paralysis, like one of those fearfully beautiful automata from Dr Coppelius's workshop. And as for Molly, Jagger's housekeeper (Laila Morse) -- what a pair of wrists! In some ways she was the most perfect translation from page to screen. Do you recall how Dickens describes her? "...with large faded eyes, and a quantity of streaming hair. I cannot say whether any diseased affection of the heart caused her lips to be parted as if she were panting and her face to bear a curious expression of sadness and flutter....as if it were all disturbed by fiery air.."

The men worked hard. Pip is a rich creation, very self aware for a Dickens hero, anxious to conceal his less attractive qualities, but in telling us his story he lets much slip. This is difficult to bring off in the third person narrative we had here, but this Pip (Ioan Gruffudd) came through as smart and pushy. Joe (though no attempt was made to render him fair-haired or blue-eyed) looked every inch a blacksmith, yet gentle withal (Clive Russell). Magwitch (Bernard Hill) was as rough a diamond as you could find. Jaggers I've always seen as more bristling and menacing than Ian McDiamid made him, but I suppose I'll always be a Francis L. Sullivan man. Wemmick (Nick Woodeson) was bang-on.

We lost Joe's wonderfully meaningful incoherence. And this was a considerable deprivation. The barely repressed outrage at Jaggers's offer of compensation for the loss of Pip's "services" tells us all we need to know of Joe's unconditional love for Pip. Jaggers cautions Joe, saying:

"Now, Joseph Gargery, I warn you, this is your last chance. No half measures with me. If toy mean to take a present that I have it in charge to make you, speak out, and you shall have it. If on the contrary you mean to say -"

And is assaulted by Joe's answer, which takes up and echoes to considerable rhetorical effect the cautionary tag "you mean to say":

"Which I meantersay….that if you come into my place bull-baiting and badgering me, come out! Which I meantersay as sech if you're a man, come on! Which I meantersay that what I say, I meantersay and stand or fall by!" The positive emotional power of the words represents the very essence of Joe. This is sacrificed and replaced by a mumbling affectionate reticence. We also lost Tickler. We lost aspects of Orlick and the connections between Compeyson, Magwitch and Miss Havisham and Jagger's motives in saving Estella. And all the fun of the Aged P's Castle. But when it came to it, they lacked the courage to use Dickens's original sad ending. What was that about being sentimental?

Robert Giddings Bournemouth University.Published in The Dickensian