Charles Dickens, Henry Benge, and the Great Staplehurst Railway Crash

A good man, a great man, and a simple mistake.

Travel between London and Paris, a trip that would have taken days a generation before, was now, in the summer of 1865, accomplished in a matter of hours (southeasternandchathamrailway.org). This was because of coordination between the railways and the steamship companies crossing the English Channel. The railways ran special tidal trains timed to meet the ships coming in from the continent. These ships needed the assistance of high tide to make the crossing, thus the train schedules changed daily with the tides (Johnson, 1952, p. 1018).

Henry Benge

Henry Benge1, 33-year-old foreman of a work crew of platelayers2 and carpenters for the South Eastern Railway (SER), sat at his breakfast table on the morning of Friday, June 9, 1865, thumbing through a well-worn copy of the SER timetable he used to plan his crew’s work schedule each day (RA-Doc, 41).

Benge, a local man born in nearby Marden and living with his wife, Martha, and three children in Headcorn (EC), had been with the SER for 10 years. Two years earlier, in 1863, he had been promoted to foreman with a salary of a guinea a week, 3 shillings more than his crew’s salary of 18 shillings (MT, Gallimore).

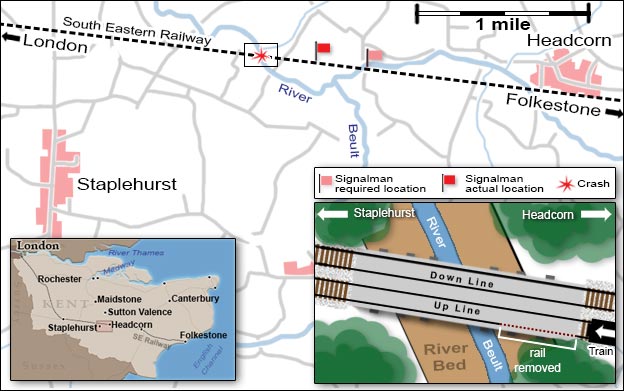

For much of the spring Benge and his crew had been working on the railway’s bridges between Headcorn and Staplehurst. Lately, the work was concentrated on the bridge over the river Beult closest to the town of Staplehurst (MT, Allen). The Beult, a raging river in wet weather was, on this fine June afternoon, nothing more than a muddy ditch. The 100-foot bridge that spanned this stream consisted of cast-iron girders resting on three-foot-thick brick piers. Nestled into the iron girders were wooden timbers to which the rails were fastened (RA). These wooden timbers, or baulks, rotted with time in the damp English weather and needed to be replaced. This involved removing the rails from atop the baulk, taking out the rotted timber, and replacing it with new timber fashioned by carpenters on the work site (MT, Coleman).

At 2:45 that afternoon Benge watched as an up train3 passed his worksite right on schedule. As the last of the carriages disappeared toward London, Benge ordered his crew to begin the task of removing the up rail on the Headcorn side of the bridge so they could replace the rotting timber below (MT, Allen). His morning check of the timetable showed that the next train, a tidal train from Folkestone, would not arrive at Staplehurst station, 1 mile up the track, until 5:24 pm, giving he and his crew plenty of time to complete the hour-long task (KG2, Aug 1).

As usual, Benge sent his signalman, John Wiles4, a 23-year veteran with the SER, down the line to warn any approaching trains of danger. Railway policy called for a signalman to be a minimum of 1,000 yards from a work site where rails had been removed (KG2, Aug 1). On this afternoon Wiles walked his usual distance of 10 telegraph poles down the line. This method of measuring distance was common among railway men despite being unreliable. The distance between poles was not standard and these poles were placed closer together than usual because of soft ground in the area. Later reports differ on Wiles’ distance from the worksite, but all were consistent in saying that the signalman was only about halfway to the 1,000-yard requirement. Wiles later reported that in the weeks that he had been acting as signalman at the Beult worksite, he had successfully stopped several other trains from this location (MT, Wiles). These were ballast trains which had all had been travelling at substantially less than the usual tidal train speed of 50 miles per hour (RA-Doc, 42).

Wiles carried with him a red flag and two fog signals. Fog signals were explosive devices that were attached to the rail and exploded with a loud bang when a train rolled over them, alerting the driver of danger ahead. Railway policy called for fog signals to be placed every 250 yards for 1,000 yards from a work site where rails had been removed. Wiles did not place the fog signals saying later that he had been told to use them only during foggy weather (RA-Doc, 42).

Back at the worksite, Benge and his crew had finished removing 42 feet of rail and 13 feet of timber below the rails on the Headcorn side of the bridge. Work had just begun on removing another stubborn section of timber when they heard the unmistakable blast of a train whistle (MT, Coleman).

Inside the train, 10-year veteran driver George Crombie5 had just passed Headcorn station travelling at approximately 50 miles per hour, when he saw a signalman waving a red flag ahead of the train. He immediately gave two blasts of the locomotive’s whistle that would alert the guards in the brake vans, both behind the tender and at the rear of the train, to apply their brakes (WM). He then shut off the steam to the Cudworth locomotive (RM) and reversed the engine (MT, Crumble). It was later estimated that it would take the train between 700 and 1,300 yards to come to a compete stop. Crombie, with his human freight of 110 souls, was less than 500 yards from the dismantled bridge (MT, Eborall).

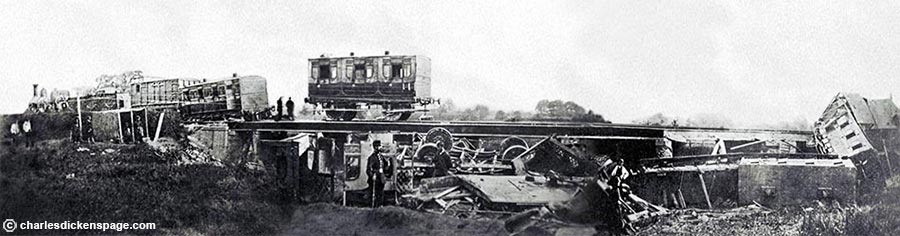

The first class carriage in which Charles Dickens and the Ternans were riding sits in the middle of the bridge in this photo montage taken in the aftermath of the accident. The carriage had been placed back on the rails.

Charles Dickens

Fifty-three-year-old Charles Dickens, with his travelling companions Ellen Ternan and her mother, left Paris at 7:00 am June 9, 1865 (Slater, 2009, p. 534), bound for Boulogne where they boarded a steamship for England. The short vacation in France had done Dickens a world of good as he had been ill most of the previous winter and spring. They crossed the Channel and left the Folkestone railway station on the 2:38 tidal train for London (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 959).

Dickens and Staplehurst by Gerald Dickens

At 3:11 the train passed Headcorn station, about two minutes late (RA-Doc, 43), and entered what was known to railway men as the "galloping ground," the straightest and fastest part of the run, travelling at speeds of close to 50 miles per hour (SM, 37).

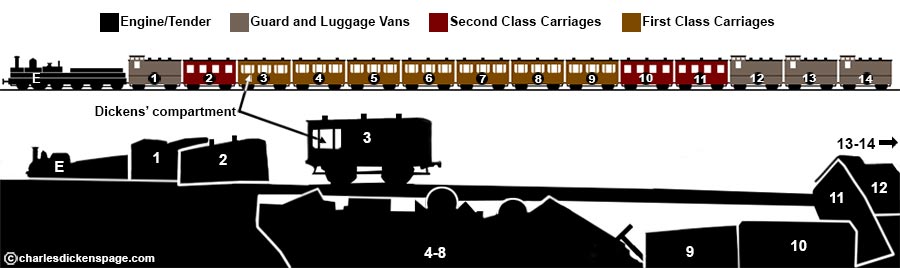

Dickens later described what happened next. "Suddenly we were off the rails and beating the ground as the car of a half-emptied balloon might do" (Letters, 1999, v. 11, p. 56). As the train, estimated at still traveling between 20 and 30 miles per hour, hit the bridge where the rail section was removed, the engine, tender, guard’s van, one second class carriage, and the first class carriage in which Dickens and the Ternans were riding, jumped the gap in the rails, because of momentum and just plain luck, and continued to the opposite bank of the river, off the rails but still in the roadbed. The rear coupling on Dickens’ carriage broke loose and the next six first class carriages plunged off the bridge and into the water and mud below (Slater, 2009, p. 535) (RA-Doc, 43).

The carriage containing Dickens and the Ternans was dragged partially off the bridge by the carriage behind before the coupling broke. The passengers in each of the three compartments were violently thrown to one end. Dickens, quickly regaining his composure, quieted Ellen and her mother and climbed out the window of the carriage, it being railway policy to keep the doors locked from the outside (Slater, 2009, p. 535).

Dickens was somehow able (he was, of course, reluctant later to discuss his fellow travelers.6) to get Ellen and her mother out of the carriage to safety. He then had the presence of mind to go back to the carriage and get a bottle of brandy and his top hat, which he used to carry water to the many injured passengers (Kaplan, 1988, p. 459). He later wrote "No imagination can conceive the ruin of the carriages, or the extraordinary weights under which the people were lying, or the complications into which they were twisted up among iron and wood, and mud and water" (Letters, 1999, v. 11, p. 56).

He worked among the injured, dead, and dying for hours before returning to his carriage one last time to retrieve the manuscript of the latest installment of his current novel, Our Mutual Friend 7. The crash scene well in hand, he finally took one of the trains that arrived to carry help to the crash site, back to London (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 961).

Aftermath

The crash resulted in 10 dead and dozens injured (KG1, Jun 13). When asked at the scene how the accident had occurred, Henry Benge, foreman of the work crew that had removed the rail, replied "Why, to tell you the truth, sir, I mistook the time, and looked at the Saturday time instead of the Friday" (KG2, Aug 1). Benge was not expecting the tidal train until 5:20 when, in fact, it was due at Staplehurst at 3:19. As a result Benge, and his immediate supervisor Joseph Gallimore, were charged with manslaughter (MT, Moore).

At the trial Gallimore was acquitted and the judge, in passing sentence, told Benge, "you have been found guilty of culpable negligence in the performance of your duty, which resulted in death. The jury having expressed the opinion, with which I very much agree, that being in command over a body of men employed in taking up the rails ought not to be entrusted to a mere labourer who works with his pickaxe and shovel at the same employment". The judge went on to commend Benge for his excellent reputation for sobriety and steadiness before passing the relatively light sentence of 9 months in prison (KG2, Aug 1). The engine driver, George Crombie, was dismissed from service, it being alluded to during the trial that had he been more attentive, and seen the distress flag sooner, the accident may have been avoided (KG2, Aug 1).

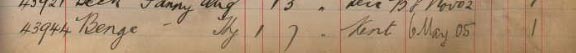

Henry Benge, after finishing his prison term, which was reduced to six months, did not return to railway work. He instead worked as a farm laborer for the rest of his life (EC). The remorse that he carried with him after his role in the death of 10 persons on that fateful day in 1865 stayed with him and he was eventually committed to the Kent County Lunatic Hospital in Maidstone where he died on May 6, 1905 (LP). He is buried in the St. Mary the Virgin churchyard in Sutton Valence, Kent, just 3 miles from the railway bridge over the River Beult (SM, 39) (BMB).

Hospital record showing Benge's death on May 6, 1905

Charles Dickens reported that while he kept a cool head during the accident, and in giving assistance afterwards, that he was "quite shattered and broken up" upon his return to London (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 961). Indeed, he continued to experience what today would be termed post-traumatic stress disorder for the rest of his life. Although he did, by necessity, return to railway travel after a time, the anxiety of doing so stayed with him. Three years after the accident he wrote, "to this hour, I have sudden vague rushes of terror, even when riding in a hansom cab, which are perfectly unreasonable but quite insurmountable. I used to think nothing of driving a pair of horses habitually through the most crowded parts of London. I cannot now drive, with comfort to myself, on the country roads here; and I doubt if I could ride at all in the saddle" (Hogarth, 1903, p. 697).

Dickens died on June 9, 1870, 5 years to the day after the Staplehurst railway crash, the trauma of the accident an attributing factor to his early death (Slater, 2009, p. 613).

Footnotes

1 - Some later reports erroneously referred to Henry Benge as John Benge or Genge. (back)

2 - Railway employees responsible for the maintenance of the rails. (back)

3 - So called because it was headed toward London, or up the line. (back)

4 - Alternately referred to as Whiles, White, or Wills in later reports. (back)

5 - Alternately referred to as Crumbre and Crumble in later reports. (back)

6 - See The Mystery of Ellen Ternan (back)

7 - In the Postscript for Our Mutual Friend Dickens writes: "On Friday the Ninth of June in the present year, Mr. and Mrs. Boffin (in their manuscript dress of receiving Mr. and Mrs. Lammle at breakfast) were on the South Eastern Railway with me, in a terribly destructive accident. When I had done what I could to help others, I climbed back into my carriage–nearly turned over a viaduct, and caught aslant upon the turn–to extricate the worthy couple. They were much soiled, but otherwise unhurt. The same happy result attended Miss Bella Wilfer on her wedding day, and Mr. Riderhood inspecting Bradley Headstone’s red neckerchief as he lay asleep. I remember with devout thankfulness that I can never be much nearer parting company with my readers for ever, than I was then, until there shall be written against my life, the two words with which I have this day closed this book:–THE END." 2 September 1865 (back)

Sources

RA - Railways Archive (via Internet Archive)

RA Doc - Railways Archive Document (via Internet Archive)

RM - Railway Magazine - July to December 1907

KG1 - The Kentish Gazette - 13 June 1865 (subscription service)

KG2 - The Kentish Gazette - 1 August 1865 (subscription service)

MT - Maidstone Telegraph - 24 June 1865 (subscription service)

WM - The Western Morning News - 14 June 1865 (subscription service)

SM - The Strand Magazine - July-December 1906

EC - England Census 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901 (subscription service)

BMB - Church of England Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials 1538-1914 (subscription service)

LP - UK Lunacy Patients Admission Registers 1846-1912 (subscription service)