Charles Dickens'

A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities - A Story of the French Revolution

A Tale of Two Cities - Published in weekly parts Apr 1859 - Nov 1859

Charles Dickens' twelfth novel was published in his new weekly journal, All the Year Round, without illustrations. Simultaneously with the weekly parts, the novel was also published in monthly parts with illustrations by Hablot Browne. An American edition was also published, in slightly later weekly parts (May to December 1859), in Harper's Weekly (Patten, 1978, p. 276).

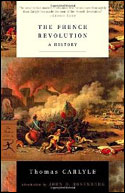

The novel, which begins It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, is set against the backdrop of the French Revolution and Dickens researched the historical background meticulously, using his friend Thomas Carlyle's History of the French Revolution as a reference (Goldberg, 1972, p. 101). This historical accuracy, with less reliance on character development and humor, led to the rather un-Dickensian feel of the book (Watts, 1991, p. 115).

Plot

(contains spoilers)

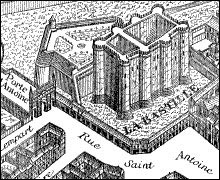

The year is 1775 and Dr Alexandre Manette, imprisoned unjustly 18 years ago, has been released from the Bastille prison in Paris. His daughter, Lucie, who had thought he was dead, and Jarvis Lorry, an agent for Tellson's Bank, which has offices in London and Paris, bring him to England.

Skip ahead 5 years to 1780. Frenchman Charles Darnay is on trial for treason, accused of passing English secrets to the French and Americans during the American Revolution. He is represented by Stryver and is acquitted when eyewitnesses prove unreliable partly because of Darnay's resemblance to barrister Sydney Carton.

In the years leading up to the fall of the Bastille in 1789 Darnay, Carton, and Stryver all fall in love with Lucie Manette. Carton, an irresponsible and unambitious character who drinks too much, tells Lucie that she has inspired him to think how his life could have been better and that he would make any sacrifice for her. Stryver, Carton's barrister friend, is persuaded against asking for Lucie's hand by Mr Lorry, now a close friend to the Manettes. Lucie marries Darnay and they have a daughter.

Meanwhile, in France, Darnay's uncle the Marquis St. Evremonde is murdered in his bed for crimes committed against the people. Charles has told Dr. Manette of his relationship to the French aristocracy, but no one else.

By 1792 the revolution has escalated in France. Mr Lorry receives a letter at Tellson's Bank addressed to the Marquis St. Evremonde whom no one seems to know. Darnay sees the letter and tells Lorry that he knows the Marquis and will deliver it. The letter is from a friend, Gabelle, wrongfully imprisoned in Paris and asked the Marquis (Darnay) for help. Knowing that the trip will be dangerous, Charles feels compelled to go and help his friend. He leaves for France without telling anyone the real reason.

On the road to Paris, Darnay (St Evremonde) is recognized by the mob and taken to prison in Paris. Mr Lorry, in Paris on business, is joined by Dr. Manette, Lucie, Miss Pross, and later, Sydney Carton.

Dr. Manette has influence over the citizens due to his imprisonment in the Bastille and is able to have Darnay released but he is retaken the next day on a charge by the Defarges and is sentenced to death within 24 hours.

Sydney Carton has influence on one of the jailers and is able to enter the cell, drug Darnay, exchange clothes, and have the jailer remove Darnay, leaving Carton to die in his stead.

On the guillotine Carton peacefully declares "It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known" (A Tale of Two Cities, 1859, p. 358).

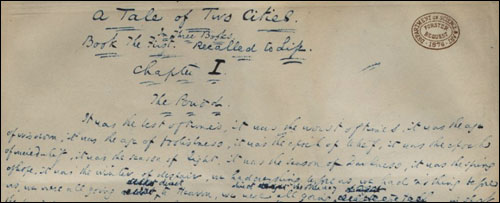

The original manuscript of A Tale of Two Cities at the Victoria and Albert Museum

Complete List of Characters:

Character descriptions contain spoilers

La Guillotine

Although a mechanical device used for beheadings had been in use for centuries, the guillotine is best known for its use during the Reign of Terror in France during the French Revolution where the device, which takes its name from Dr. Guillotin, was used for thousands of "humane" beheadings. The guillotine was still in use well into the 20th century (Wikipedia).

Dickens witnessed a beheading by guillotine in Rome in 1845 which he described in Pictures from Italy:

"[The prisoner] immediately kneeled down, below the knife. His neck fitting into a hole, made for the purpose, in a cross plank, was shut down, by another plank above; exactly like the pillory. Immediately below him was a leathern bag. And into it his head rolled instantly.

...The eyes were turned upward, as if he had avoided the sight of the leathern bag, and looked to the crucifix. Every tinge and hue of life had left it in that instant. It was dull, cold, livid, wax. The body also.

There was a great deal of blood... A strange appearance was the apparent annihilation of the neck. The head was taken off so close, that it seemed as if the knife had narrowly escaped crushing the jaw, or shaving off the ear; and the body looked as if there were nothing left above the shoulder" (American Notes-Pictures from Italy, p. 391).

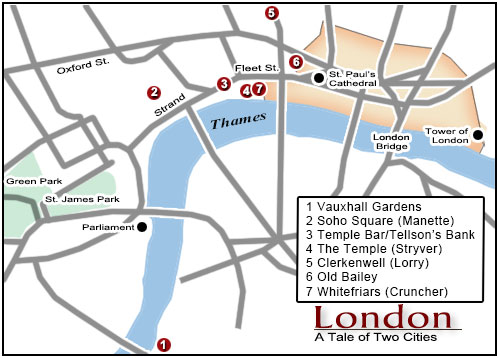

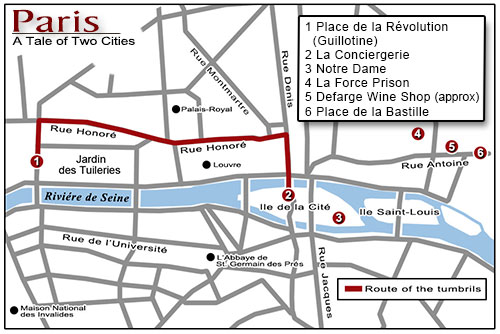

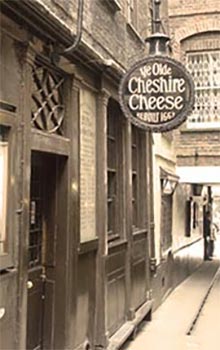

The Two Cities

Places in the novel

Resurrection Men

Dickens has Jerry Cruncher, "an honest tradesman" by day, spend his evenings as a resurrection man, or body-snatcher.

By the eighteenth century the demand for fresh corpses for use in medical training had outstripped the supply, which could only legally be obtained from executed murderers. The dread of dissection after execution being considered an additional deterrent for would-be murderers.

To supply this demand for fresh corpses surgeons and anatomists turned to resurrection men or body snatchers. Strange bedfellows indeed!

Ruth Richardson, in her book Death, Dissection, and the Destitute described a common method these men used to obtain fresh corpses:

"Bodysnatchers invariably worked in small gangs, to allow at least one person to be on the look-out for potential danger. Freshly-filled graves meant that in general the digging was easy, as the earth was still loose, and not yet compacted by settling. Canvas would sometimes be laid by the grave to receive the displaced earth, so as to leave none on surrounding turf. A hole would be dug at the head of the grave, down to the coffin, and hooks or a crow-bar inserted under the lid. The weight of earth on the rest of the lid acted as a counter-weight, so that when pressure was exerted the lid invariably snapped across and the body could be hoisted out of the grave with ropes. Sacking would be heaped over the lid beforehand to deaden the sound of cracking wood. At this stage in the proceedings, the corpse should in principle have been stripped and the grave-clothes thrown back, before the earth was shoved back into place, and the body trussed up neck and heels in a sack" (Richardson, 1987, p. 59).

It is interesting to note that a corpse was not considered to be property thus the stealing of a corpse was only a misdemeanor. That was the reason that the grave-clothes, and any other articles about the corpse were thrown back in the grave, the taking of which would be considered a felony.

Cases arose in the early nineteenth century of surgeons buying fresh corpses whom they doubtless knew had been murdered for the purpose.

Parliament, seeking an end to this heinous practice, passed the Anatomy Act of 1832. Under this law the bodies of unclaimed dead from workhouses could be used for dissection. The reaction to this practice was widespread uprising in the workhouses as what was viewed as a punishment to murder was now considered a judgement on the poor (Richardson, 1987).

- Sketches by Boz |

- Pickwick |

- Oliver Twist |

- Nickleby |

- Old Curiosity Shop |

- Barnaby Rudge |

- Chuzzlewit |

- Christmas Carol |

- Christmas Books |

- American Notes |

- Pictures from Italy |

- Dombey and Son |

- Copperfield |

- Bleak House |

- Hard Times |

- Little Dorrit |

- Tale of Two Cities |

- Great Expectations |

- Our Mutual Friend |

- Edwin Drood |

- Minor Works |

- The Uncommercial Traveller |

- Short Stories

Royal Executioner of France

Royal Executioner of France