Special Guests > Gidding: Nicholas Nickleby Review

Nicholas Nickleby Film Review [1]

Nicholas Nickleby, written and directed by Douglas McGrath

Review by Robert Giddings

School of Media Arts and Communication, Bournemouth UniversityReprinted with the kind permission of the author

Published on this site April 15, 2004

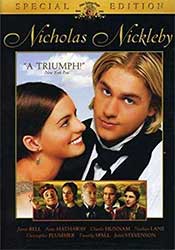

Nicholas Nickleby (2002) Starring Charlie Hunnam, Anne Hathaway, Jamie Bell, and Christopher Plummer

…All that

had given 'Pickwick' its vast popularity, the overflowing mirth, hearty

exuberance of humour, and genial kindliness of satire, had here the advantage

of a better laid design, more connected incidents, and greater precision of

character. Everybody seemed immediately to know the Nickleby family as well as

his own. Dotheboys…became a household word. Successive groups of Mantalinis,

Kenwigses, Crummles, introduced each its little world of reality, lighted up

everywhere with truth and life…From first to last they were never for a moment

alien to either the sympathies or the understanding of any class; and there

were crowds of people at this time that could not have told you what imagination

meant, who were not adding month by month to their limited stores the boundless

gains of imagination”. [2]

Now a major motion picture”. Ah yes. So it is.

There was a ticket offer in the Radio Times. In the UK, the Pastimes

retail chain ran a lavish promotion. Then came the film tie-in paperback with

top-hated young Charlie Hunnam on the cover. Boz rides again. And again. In the

USA, (though not, as yet, in the UK) readers can enjoy the new Penguin

American edition” of Nicholas Nickleby edited by Douglas MacGrath

who (by a coincidence into which it would be just too, too tedious to explore)

also directed the film. They seem to be making quite a splash with this film.

It was a very important book, too, in its day.

Nicholas Nickleby 1839 was a very popular novel, regularly

selling 50,000 copies of its monthly installments and bringing a profit of

£14,000.[3]

The

serialization of Pickwick Papers over eighteen months from March 1836

was a triumph previously unknown in literature, with sales topping 40,00 a month

at its height. Serialization, with advertisements in the parts, was rapidly to

become standard. Pickwick Papers showed what could be done. Advertising

as an element of the mass media was well on the way. Chapman and Hall decided

to publish the book cloth bound in volume form after its serial run in 1837.

This conferred the status of literature on Pickwick Papers and set it

apart from ephemeral periodic journalism.

This was a landmark in the history of attractive, quality book

publishing. Its success at home and abroad was previously unknown in

literature. Dickens commented, "My

friends told me it was a low, cheap form of publication, by which I should ruin

all my rising hopes, and how right my friends turned out to be, everybody

knows".

Publishers underwrote serial publishing costs with

advertising revenue. A good long story was needed to build up readership

loyalty. A successful author was

therefore a desirable commodity. Publishers wanted success repeated. We are not

far from the world of commercial TV and Harry Potter publishing. Dickens’s

genius lay in his capacity to combine commercial potential with artistic

integrity. He was gifted with invention that never

dried up. It’s hard to credit, yet he was writing Oliver Twist at the

same time as Pickwick Papers. He finished this in October 1837 and Oliver

Twist completed in March 1839. He then signed the contract for Nicholas

Nickleby 19 November 1837. The new novel was serialized in twenty monthly

parts from March 1838 to October 1839. Public appetite for Nicholas Nickleby was

aroused by skillful publicity and it sold an unprecedented 50,000 copies each

month when first serialized. As Sylvere Monod commented, Nicholas

Nickleby was the supreme and striking confirmation of the triumph of Pickwick

Papers[4].

Dickens played a major role in constructing the novel” in our culture.

And, by the way, in January 1839 he was already working on Barnaby Rudge.

It’s

often claimed that much of his work is rambling as a result of its being

written for serial publication with the printer’s boy waiting at his elbow as

he scribbles away. But he owes much to his deep immersion in 18th

century English fiction, especially Smollett and Fielding. The picaresque

life-and-adventures form suited Dickens’s imagination. He could have his hero

and a companion travel around, involved in various adventures -- Pickwick/Sam

Weller; Nicholas/Smike; Martin Chuzzlewit/MarkTapley -- and have the combining

narrative held loosely on a thread gathered together at the conclusion. This is

certainly the shape of Nicholas Nickleby.

The plot is fairly sprawling but rich in characters

and incidents, with plenty of those anticipated Dickensian ingredients –

melodrama, pathos and comedy. Nicholas and Kate are

thrown penniless into life on their father’s death. Scatter-brained Mrs

Nickleby seeks help from her late husband's brother, wicked uncle Ralph. Ralph

gets Nicholas a teaching job at the dreadful Dotheboys Hall, Yorkshire and is

apprentices Kate with Mrs Mantalini, a milliner. Nicholas is appalled at the

cruelties of Squeers and thrashes him when he beats Smike, a poor drudge of a

pupil, for running away. Nicholas then flees to London, taking the unfortunate

Smike with whom he has many colourful adventures. Kate suffers the insulting

advances of Mrs Mantalini's affected husband and Ralph’s aristocratic

associates.

After numerous

other adventures, it all works out well. He falls in love with Madeline Bray,

daughter of one of Ralph’s victims. Ralph plans to marry Madeline off to Arthur

Gride, who intends to diddle Madeline out of her property. Ralph villainies are

exposed, including the fact that he’s Smike’s father, who unfortunately dies,

telling Nicholas on his deathbed of his everlasting love for Kate Nickleby. Ralph hangs himself. Nicholas marries

Madeline. Kate marries the nephew of Nicholas’s philanthropic employers, the

Cheeryble brothers.

We are used to

radio, film and TV dramatizations of the classics, the media’s continuation of

literature (to recycle that phrase of General Klaus von Clausewitz), by other

means. And Dickens’s fiction, I dare say, has always yielded useful fodder for

stage and screen. It wasn’t just Dickens. The Victorians indeed were well used

to stage versions of novels of the day, not only East Lynne, (based on

the novel by Mrs Henry Wood, subsequently filmed seventeen times and twice

televised); Lily of Killarney (stunning melodrama by Dion Boucicault,

based on Gerald Griffin’s novel The Collegians, also provided libretto

of celebrated Victorian opera by Benedict) and Lady Audley’s Secret

(based on the novel by Mary Elizabeth Bradden, interestingly dramatized for

television two years ago) but more serious books as well. And this was not all.

There was a long

standing British tradition of dramatizing novels that in due course had

dutifully (and profitably) recycled Defoe, Fielding, Goldsmith, Smollett,

Richardson and Sir Walter Scott. (Who in due course provided almost as much

material for operatic libretti as Shakespeare). Even such a rambling work as

Pierce Egan’s Life in London made it to the boards. Ransacking Dickens

for suitable stuff has a very long tradition stretching right back to the

production at the Adelphi Theatre in October 1834 of A Bloomsbury

Christening in a version for the stage by the novelist’s friend, John

Baldwin Buckstone. Stage versions of Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist and Nicholas

Nickleby duly followed and writers such as Buckstone, W. T. Moncrieff and

Edward Stirling continued to dramatize his fiction. Not only did the novels

provide an abundance of comic and melodramatic incident, but rich parts for

actors to get their teeth into. W. J. Hammond was for a time the Sam

Weller, and Mrs Keeley delivered pathos in generous measure as Oliver, Smike,

Little Nell and Barnaby Rudge. Dickens was sometimes a willing collaborator.

The novelist’s feelings about all this were ambivalent. He was in part thrilled

that early staging bestowed instant popularity on his work, but on the other

hand as dramatizations frequently went on before serialization was completed,

there was the danger of giving the plots away.

By 1850, with his

reputation and fame well established, there had been an estimated 240 stage

versions of his fiction. Interestingly enough, 25% of these were versions of Nicholas

Nickleby.

Dickens attracted

filmmakers from the very beginning.

Dotheboys Hall was the first bit of Boz put on the silver screen in

1903.[5]

Nicholas Nickleby was filmed again in 1916.[6]

Alberto Cavalcanti made a brave attempt in 1947 and managed to retain quite a

lot of the novel’s ingredients, but somehow the vitality of the novel

evaporated in the process. [7]

A great deal of

nonsense has been written about the suitability, nay the inevitability of

Dickens and film. The fact that so many of his novels have been filmed proves

nothing. Arithmetic has but modest value in aesthetics. To argue that Dickens’s

suitability for film is demonstrated by the fact that so many of his fictions

have been filmed is like arguing Haydn is a greater symphonist than Beethoven

because he composed 104 symphonies against Beethoven’s humble nine.[8] I think Dickens provides several ingredients

basic to popular cinema -- striking characters, melodrama and a warm and human

moral vision. But a very considerable about is of the real Dickens gets lost in

translation from page to big screen. This version of Nicholas Nickleby

demonstrates this rather well.

The plot of Nicholas

Nickleby may seem a muddle but it’s packed with vitality and riotous

observation. It survives to excite generations of readers. Even though much of

its contemporary relevance is lost today, Nicholas Nickleby obviously tempted

film makers from the very beginning, has several times been serialized on

British television[9] and

brilliantly dramatized for the stage by David Edgar for the Royal Shakespeare

Company in 1982[10]. He was

already well-established playwright and had previously dramatized books for the

stage (Mary Barnes and The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs) when Trevor

Nunn, artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, asked him to make a

stage version of Dickens novel:

…and the

choice was already down to two: ‘Our Mutual Friend’ and ‘Nickleby’…The extent

of my Dickensian scholarship can be judged from the fact that my first question

was ‘Is ‘Nicholas Nickleby’ the one with Mrs Gamp in it”.[11]

This version of Nickleby

is nevertheless one of the most vigorous and convincingly Dickensian”

versions of a Dickens novel ever made.

The playwright has

described how this extraordinary production was collectively worked up with the

whole company in research, discussion, experiment, exercises and workshops.

This process led to their increased awareness of the organic wholeness of Nicholas

Nickleby despite its apparent rambling structure. No element could be

deleted without damaging the work’s intentions. They realized that even the

Kenwigs could be sacrificed as this plot encapsulated, in comic form, the

obsession of the whole”.[12] They realized that beneath the Dickensian”

surface level was a rich portrait of a society very like our own, in which

rapid technical and economic change had created considerable economic

opportunity for some along with social upheaval, considerable hardship,

insecurity and doubt. In the process David Edgar’s team realized that to do

justice to the novel, they would need the space of a two evening production. [13] And once again a major filmmaker has been

drawn to this novel.

Douglas McGrath,

who was responsible for the excessively pretty version of Jane Austen’s Emma,

has now written and directed Nicholas Nickleby. Emma contained

little evidence that he might have a sure touch for early Dickens. And indeed

he hasn’t.

Dickens’s fiction

offers splendid opportunities to the film industry. His work has a universal

appeal and consequently a certain attraction to potential audiences on both

sides of the Atlantic as well as elsewhere. His novels are not just classics”

and therefore educationally OK, but they’re seen as wholesome” and

improving and consequently good for family viewing. Plenty of action. Plenty of

parts for character actors. And in casting, it will certainly be possible to

use American stars as well as British thespians. The heritage industry makes

Dickens films easy to market. In this respect, it was interesting to note the

special promotion of Nicholas Nickleby in the British retail chain Pastimes.

There are opportunities for video, DVD, book tie-in as well as additional

merchandize. And yet there are severe problems to be met and dealt with. The

two most obvious concern the long, complex and elaborated nature of Dickens’s

novels and the question of style.

Plot and

Story.

Filming or

televising Dickens imposes considerable time restrictions. Dickens’s fiction

was serialized over weeks or months. Most of the major novels in monthly

episodes over eighteen months. The results are novels of considerable length,

and the story often elaborated with various interlocking plot lines. Even

serializing such novels for broadcasting will only result in five hours or so

of radio or television drama. A film for cinema release may last two or more

hours at the most. Consequently pruning cannot be avoided. But what can be cut?

There has to be a firm understanding of necessary story outline (how can we

make this story coherently work within the time we have?) and a firm grasp of

the plot, i.e. what the novel is about, its leading themes and preoccupations,

what Dickens is trying to tell you. Can whole and entire episodes be omitted

without damage to the effect of the whole? Can we, without too much of a sense

of loss, cut out whole characters? Or merely cut down the part they play?[14]

To accommodate Nicholas

Nickleby to the big screen Douglas McGrath has quite ruthlessly dealt with

the novel and mangled the plot quite seriously. Only the barest outline of the

classic Smollett picaresque storyline remains. Uncle Ralph’s willingness to

prostitute his niece by sending her to milliner Mrs Mantalini goes for nothing

(we do not even have Mr or Mrs Mantalini, so the pair of ‘em must have gone ‘to

the damnation wows-wows’). There’s no Kenwigs. No Mr Lillyvick, so no

romance with Miss Petowker. Mrs Nickleby’s admiring lunatic vegetable-throwing

neighbour has been erased. There’s no Tim Linkinwater, the Cheerybles fat and

loyal clerk, an obvious analogy to Ralph Nickleby/Newman Noggs. There’s no use

of Squeers using Peg Sliderskew (A short, thin, weasen, blear-eyed old

woman, palsy stricken and hideously ugly”) to spy on Gride, so we lose the

magnificent operation by Frank Cheeryble and Noggs, who intercept these

machination. The plot to marry off

Nicholas’s love, Madeline Bray, has been butchered. This I think is a serious

loss as it considerably adds to our knowledge of Ralph Nickleby’s villainies.

Her father, Walter Bray, who is a selfish, misanthropic and bankrupt widower,

treats Madeline as a slave. Walter Bray is seriously indebted to Arthur Gride

and Ralph Nickleby. Ralph’s plot is that Madeline should marry Gride (who is

about seventy) and that this should cancel Walter Bray’s debt. Peg Sliderskew

discovers various documents that detail Gride’s control over various people. By

marrying Madeline he had hoped to come into a fortune from Bray. In the novel,

Walter Bray dies and Madeline is thus saved from having to marry Gride. Arthur

Gride is later murdered by burglars. All this falls disappears in the film

version. And so on[15].

Well, what have we left? The omission of quite

considerable sections of the plot is not the only loss in this film. The

characterisation in this novel is probably not all that rich, deep, subtle or

convincing. This was subject to early comment. An

anonymous contemporary review expresses this well:

.... The hero

himself has no character at all, being but the walking thread-paper to convey

the various threads of the story. Kate is no better; and the best-drawn

characters in the book, Mr Mantalini and Mrs Nickleby, have only caricature

parts to play; and in preserving them, thee is no great difficulty... Squeers

and Ralph Nickleby become worse and worse as the story proceeds... Squeers at

first is nothing more than an ignorant and wretched hound, making a livelihood

for himself and his family by starving a miserable group of boys. The man has

not the intellect for any thing better or worse; and yet we find at last an

adept in disguising himself, in ferreting out hidden documents, in carrying

through a difficult and entangled scheme of villainy. Ralph Nickleby makes his

appearance as a shrewd, selfish, hard-hearted usurer, intention nothing but

making and hoarding money; in the end we find him actuated by some silly

feelings of spite or revenge, by which he cannot.... make a farthing.... His

committing suicide, and that out of remorse too, is perfectly out of

character... (he) has not done anything that could expose him to legal

inconvenience..." [16]

This might not have an insurmountable problem in

filming this novel. In fact, vivid caricature works well in film. In what might

have been the leading roles of Nicholas (Charlie Hunnam) and Kate (Romola

Garai) are adequate. Charlie Hunnam is rather too young for this role

(Dickens’s Nicholas is manly and well-formed”) and does not mature as

the story unfolds. He looks uncomfortable to find himself top hated and in the

19th century when he would clearly be more at home on a beach in

California. I could not believe this pop star looking young fellow had it in

him to take it upon himself to thrash the tyrannical Squeers. We are not given

much to go on in the novel as we are told little more than that Kate is a

slight but very beautiful girl of about seventeen” but even so, I felt she was

a bit more of a mature young miss.

Mrs Nickleby (Stella Gonet) is not given much to go

on. The original’s rhapsodic dottiness has gone: ” I had a cold once...I think it was in the year eighteen hundred and

seventeen; let me see, four and five are nine, and -- yes, eighteen hundred and

seventeen, that I thought I never should get rid of ... I was only cured at

last by a remedy that I don't know whether you ever happened to hear of.... You

have a gallon of water as hot as you can possibly bear it, with a pound of salt

and sixpenn'orth of the finest bran, and sit with your head in it for twenty

minutes every night just before going to bed; at least, I don't mean your head

-- your feet. It's a most extraordinary cure. I used it for the first time, I

recollect, the day after Christmas Day, and by the middle of April following

the cold was gone. It seems quite a miracle when you come to think of it, for I

had it ever since the beginning of September...”

Ralph (Christopher

Plummer) is really the central character, who holds all the elaborated threads

together. He is the star of the show rather than the eponymous hero. Plummer

manages to suggest that something in the wrinkles of his face and his cold

restless eye, which seemed to tell of cunning that would announce itself in

spite of him”. McGrath occasionally works into Ralph’s dialogue parts of

Dickens’s authorial comment to good effect: Speculation is a round game;

the players see little or nothing of their cards at first starting; gains may be

great – and so may losses. The run of the luck went against Mr Nickleby; a

mania prevailed, a bubble burst, four stockbrokers took villa residences at

Florence, four hundred nobodies were ruined….” For reasons never explained

in the film, Ralph seems to live and work in a natural history museum. Never

mind, he is old fossil, well suited to the company of dehydrated reptiles. It

is great performance and the silky, sinister voice is a masterstroke.

Newman Noggs’s

role suffers considerable reduction in this version, but Tom Courtenay manages

the best he can with what he has left. He strives to look the part. He’s

slightly dotty, but by no means the raving ex-alcoholic eccentric that Dickens

painted him: A tall man of middle age, with two goggle eyes, were of one

was one was a fixture, a rubicund nose, a cadaverous face, and a suit of

clothes…. Much the worse for wear, very much too small, and placed upon such a

short allowance of buttons that it was marvellous how he contrived to keep them

on”.

We get the sense

that Noggs is very well aware of what Ralph is up to and comically raises his

fists to him from a position of safety, but much of this vital character has

been surgically removed, not without considerable loss. He has an interesting

back story as a former well-to-do gentleman who was almost certainly ruined by

Ralph, who himself offers this biographical explanation to Mr Bonney, a fellow

swindler:

…Newman Noggs

kept his horses and hounds once…and not many years ago either; but he

squandered his money, invested it anyhow, borrowed at interest, and in short

made first a thorough fool of himself, and then a beggar. He took to drinking,

and had a touch of paralysis, and then came here to borrow a pound, as in his

better days I had – had…done business with him. I couldn’t lend it, you

know…But as I wanted a clerk just then, to open the door and so forth, I took

him out of charity, and he has remained with me ever since. He is a little mad,

I think…but he is useful enough, poor creature – useful enough”.

This is obviously

a highly sanitized account of the businesslike manner in which Ralph had

fleeced Noggs in days gone by, and it would explain Noggs’s motivation for

patiently working on Ralph Nickleby’s downfall.[17]

Yet there are genuinely warm and benevolent aspects to Newman Noggs. It’s Noggs

who finds Nicholas employment with as tutor to the Kenwigs family when he comes

back to London after his adventures in Yorkshire alienate him from Ralph. It is

Noggs who warns Nicholas about the danger Kate Nickleby faces from Sir Mulberry

Hawk, while Ralph fails to protect her and Mrs Nickleby is so silly as to

flattered by Hawk’s attentions. When Ralph uses Squeers to spy on Gride and to

recover documents that may reveal dark and damaging secrets, it is Newman Noggs

(helped by Frank Cheeryble) who scupper these proceedings. In the novel we are

given the impression that Noggs’s opposition gradually mounts towards its final

climax, and does not come as a bolt from the blue, as Noggs picks up a very

deal of what transpires between Ralph and Squeers before Ralph dispatches him

about other duties. In fact, Noggs’s interference is violent and direct, as he

fells Squeers to the floor with a pair of bellows at the moment of the

schoolmaster’s supposed triumph in securing the papers he was instructed to

find. (Nicholas Nickleby, Chapters 58). At the moment of the unmasking

of Ralph, Noggs reveals the extent of his association with him:

When did I

ever cringe and fawn to you – eh? Tell me that1 I served you faithfully. I did

more work because I was poor … I served you because I was proud … and there

were no other drudges to see my degradation, and because nobody knew better

than you that I was a ruined man, and that I hadn’t always been what I am, and

that I might have been better off if I hadn’t been a fool and fallen into the

hands of you and others who were knaves…” (Nicholas Nickleby,

Chapter 59).

Squeers plays a

big part in this novel and his role is boldly tackled by Jim Broadbent. He very

nearly brings it off. Broadbent’s great strengths lie in realizing the enormous

comic potential in every day, humdrum characters, rather than larger-than-life

melodramatic villains and grotesques. He certainly does well with the comic

grotesquery of the role but fails to dig into the fiendish barbarity of the

man. However, when on stage (as it were) with his wife, Juliet Stevenson, a

wonderful enchantment takes over. They are superb together. Hilariously,

outrageously funny (Where’s my Squeery!” and their marriage

relationship is a very interesting and, as I’d guess, a fairly fulfilling one.

Smike is one of

the most difficult roles in Dickens successfully to realize in stage or screen.

There are two major difficulties to surmount. One is convincingly to portray

the terrible physical and emotional damage inflicted upon him by his parentage

and the treatment he has endured from Squeers without resorting to an

assortment of psychological and physical symptoms. The second is resisting the

tendency simply to over play the pathos of the role. Smike must remain, beneath

all the clinical apparatus, real, genuine human being, with a brave and

generous heart.

This highlights a

considerable problem in handling Dickens’s work. We know so much about him, and

have been so influenced by the not-altogether beneficial application of

off-the-peg Freudianism that critics all too frequently deploy, that our

perceptions of the character are distorted by bringing in far too much of

Dickens’s own history. It’s all very well to recall ad nauseam that the

young Dickens endured the ordeal of the blacking factory and felt his parents

had abandoned him[18]

but we have to concentrate in recreating Smike so that the character achieves

the right impact and effect upon the audience. Smike is about eighteen or

nineteen years old, and tall for his age, wearing clothes that are too small

for him, that nevertheless fit his attenuated frame. His appearance is so

strange, freakish and bizarre that when Nicholas first notices him he could

hardly bear to watch him”. Jamie Bell brings off a very difficult task here

in combining the right amount of pathos and awkwardness while yet making Smike

believable and indeed likable. It is well-graded performance, too, as much is

held in reserve for the final horrific revelation about the way Ralph treated

him as a child. The friendship between Nicholas and Smike is well established

and seems quite understandable.

Vincent Crummles

(Nathan Lane) is very well played for all he is worth. At first sight I

thought, no, this is just not going to be right. Crummles needs biggish man,

somebody on the lines of Francis de Wolff, Francis L. Sullivan or Donald

Wolfitt. But such was his sense of the histrionic that after a moment his

stature seemed to grow. Nor did this performance descend to mannerism, that so

easily could have been the case: …the face of Mr Crummles was quite

proportionate in size to his body … he had a very full under-lip, a hoarse

voice, as though he were in the habit of shouting very much, and very short

black hair, shaved off nearly to the crown of his head … to admit … of his more

easily wearing character wigs of any shape or pattern … He was very talkative

and communicative, stimulated perhaps, not only by his natural disposition, but

by the spirits and water he sipped very plentifully, or the snuff he took in

large quantities from a piece of whitey-brown paper in his waistcoat pocket”.

(Nicholas Nickleby, Chapter 22).

Mrs Crummles

(Barry Humphries) has a minor part in proceedings, but here makes a

considerable meal of it in a manner likely to give ham a bad name. Far too much

time and space is given to Highland Fling dancing Mr Folair (Alan Cumming)

who, far from remaining the shabby gentleman in an old pair of buff

slippers” is allowed to become the star of the show and far to indulge his

tartan choreographical dexterities even unto tedium.

Sir Mulberry Hawk

(Edward Fox) is here a somewhat older man-about-town than might have been

expected. This makes his all-too-obvious intentions on teenager Kate Nickleby

even sleazier. He appears an old roué, rather than a Byronic scoundrel. There’s

more of Don Pasquale here than Don Giovanni. Dickens describes Hawk as the head

of his profession in ruining young gentlemen and maintaining his ascendancy

over them: …and to exercise his vivacity upon them, openly, and without

reserve. Thus, he made them butts, in a double sense, and while he emptied them

with great address, caused them to ring with sundry well-administered taps, for

the diversion of society”. This aspect of Hawk is finely done and the

tensions between Hawk and Lord Verisopht (Nicholas Rowe) mount to quite a

crescendo.

The Cheeryble

twins (Timothy Spall and Gerard Horan) are quite magnificent. And more to the

point, they are actually convincing. This is quite an achievement, as they seem

an unlikely pair of generous philanthropists. Nevertheless, Dickens based them

on real people, whom he met through his friendship with Harrison Ainsworth.[19]

Charles Cheeryble is described as: A sturdy old fellow in a broad-skirted

blue coat, made pretty large, to fit easily, and with no particular waist; his

bulky legs clothed in drab breeches and high gaiters, and his head protected by

a low-crowned broad-brimmed white hat, such as wealthy grazier might wear…”

And Edwin, his twin brother was: Something stouter than his brother; this,

and a slight additional shade of clumsiness in his gait and stature, formed the

only perceptible difference between them”. Thus the novelist immortalised

William and Daniel Grant, who were, by the time Dickens met them, very rich

merchants, though they were formerly graziers, from Elchies, in Scotland. (Note

the grazier’s hat worn by Charles). They’d failed as shopkeepers, but went on

to deal in wool and linen in Manchester, where they thrived. A Liverpool merchant

came to them for help during a crisis and was unconditionally given £10,000. [20]They

were in real life as staggeringly generous as Dickens recounts. It would be

insidious to praise one performance above the other, as these two twins are a

delightful turn, but it seems to me Timothy Spall has a natural touch in

playing Dickens.

The loss of Alfred

Mantalini partnership is a shame. Mr Mantalini, wastrel, womaniser and

pretentious layabout, is one of Dickens’s most frolicsome naughty characters.

His name was really Muntle but it was considered an Italian name over the door

would do the business good and Mantalini he duly became. Much else besides was

false: He had married on his whiskers; upon which property he had previously

subsisted, in a genteel manner, for some years; and which he had recently

improved, after patient cultivation, by the addition of a moustache, which

promised to secure him an easy independence: his share in the labours of the

business being at present confined to spending the money”. He labours to

considerable success, eventually bankrupting his wife. The loss of the splendid

Mantalini dialogue is to be lamented. Think what a pair of quality actors would

have done with it! Take the scene at breakfast time where Alfred, having been caught

philandering, is enduring his wife’s understandable displeasure. If you will be odiously, demnebly

outrageously jealous, my soul, you will be very miserable – horrid miserable –

demnition miserable”. There is then

the sound as if he was sipping his coffee. I am miserable,” she answers. Then you are an ungrateful, unworthy, demnd

unthankful little fairy” Mantalini answers. This she denies. Do not put yourself out of humour” he

says, breaking the top of his egg, It is

a pretty, bewitching little demnd countenance, and it should not be out of

humour, for it spoils its loveliness, and makes it cross and gloomy like a

frightful, naughty, demnd hobgoblin”. Mrs Mantalini here says that she is

not to be brought round in that way. It

shall be brought round in any way it likes best, and not brought at all if it

likes that better”, retorts Mr Mantalini, with his egg-spoon in his mouth.

It’s very easy to talk”, said Mrs

Mantalini. Not so easy when one is

eating a demnition egg”, replies Alfred, for the yolk runs down the waistcoat, and yolk of egg does not match

any waistcoat but a yellow waistcoat, demmit”. (Nicholas Nickleby, Chapter 17). And while we’re on the subject, the

loss of Mrs Nickleby’s mad admirer who expresses his love for her in random

gifts of vegetables and by climbing down her chimney to declare himself is an

additional loss. He has, I think, one of the truly immortal chat-up lines: I

have estates, ma’am, jewels, light-houses, fish-ponds, a whalery of my own in

the North Sea, and several oyster-beds of great profit in the Pacific Ocean. If

you will have the kindness to step down to the Royal Exchange and to take the

cocked hat off the stoutest beadle’s head, you will find my card in the lining

of the crown, wrapped in piece of blue paper. My walkin- stick is also to be

seen on application to the chaplain of the House of Commons, who is strictly

forbidden to take any money for showing it…” (Nicholas Nickleby,

Chapter 41).

We still have,

then, a feast characters in this version of Nicholas Nickleby, despite

one or two imbalances (too much Folair, not enough Noggs). But I suppose, you

can’t have everything. For that, you have to read the book.

Problem of Style

What this new

version of Nicholas Nickleby lacks is a pervasive sense of stylistic

cohesion. It tends uncomfortably to move in and out of various styles as it

goes along. Translating Dickens from page to screen confronts filmmakers with

the problem of Dickens’s style.

We seem to have

some pretty firm idea as to the graphic qualities of this Dickensian style,

drawn very largely, I suspect, from our impressions of the original

illustrations. Examination of the evidence reveals how impossible it is

effectively to recreate this style” in terms of cinematography. Through his

first publisher, John Macrone, Dickens met George Cruikshank (1791-1878) in

1835, who did illustrations for Sketches by Boz and Oliver Twist. Cruikshank

was an experienced political cartoonist with experience of illustrating classic

novels (such as those by Fielding and Smollett) with a particular flair for the

comic.[21]

This style would be difficult to translate to screen. But the artist we tend

immediately to think of is Phiz”, Hablot Knight Browne (1815-1882). He

undertook most of the illustrations up to and including A Tale of Two Cities,

and usually worked closely and fairly harmoniously with the novelist. Brown also illustrated novels by Surtees,

Sedley, Lever and Ainsworth. Browne was inclined to caricature and grotesque

and tended to draw people either fat or thin. This would be difficult to

reproduce in film terms, working against modern film style.[22]

Dickens also used George Cattermole (1800-68) who was trained as an

architectural draughtsman and developed into a celebrated antiquarian painter.

Obviously his forte was architecture and he contributed notable illustrations

for various scenes in Barnaby Rudge, Master Humphrey’s Clock and The

Old Curiosity Shop. John Leech (1817-64) was an established illustrator of

Surtees and was employed in Punch, when he approached Dickens for a commission

after the novelist’s return from America in 1842. He notably illustrated A

Christmas Carol and the other Christmas stories. He had great strength in

homely humour and depicting terror. He used several other, rather more traditional

or academic artists for his later novels. Marcus Stone (1840-1921) was trained

as a portrait painter by his father, Frank Stone and illustrated Great

Expectations and Our Mutual Friend though he himself that he found

Dickens’s work immature. Luke Fildes (1844-1927) had studied at the Royal

Academy. He drew illustrations, in rather heavy and serious style, following

the style of Charles Collins who had already drawn the wrapper, for Edwin

Drood. [23] The problem

of coming up with a coherent and credible Dickensian style” for film based on

the original illustrations is thus extremely problematic.

Those who would

argue Dickens’ greatness” as a novelist is mainly justified by

demonstrating his greatness” as a social reformer, inevitably find

themselves having to assert that Dickens is a social realist. The novels do not

lend themselves easily to this categorization. It seems to me that Dickens is

unlike most of his contemporary writers insofar as his fiction seems much

closer to allegory, myth and dream and to have close affinities with the world

of mythological archetype. He has more

affinity with the phantasmagoric world of E. T. A. Hoffmann, Nerval, Aurevilly,

Strindberg, Dostoyevsky, Kafka and even Samuel Beckett than of early social

realist novelists such as Mrs Gaskell, Charles Kingsley, George Eliot, or

Thomas Hardy.[24]

In my view it is

ill advised to place Dickens in this context. [25]

He is a mythologist, a poet of the novel. The emphasis on socio-economic

literary exegesis, the dominance of Marxian critical theory has tended to over

estimated the realism” of Dickens, whereas his genius lies in his creation of

convincing, haunting, recognizable fantasy. Dickens draws upon and echoes

traditional sources such as the Arabian Nights, myths and British fairy

stories (note the craze for pantomime that was such a feature of the early

Victorian theatre) but this archetypal material powerfully affects readers.[26]

Although we readily think of something quaint, old fashioned, innocent, early

Victorian, Christmassy, jovial or grotesque when we hear something described as

"Dickensian" I would like to point to the quite different

qualities that really make Dickens what he is. It is no good thinking of him as

"Victorian" -- for his work is quite different from any other

Victorian novelist. It is the dream-like, otherworldly, almost mythical

quality, which makes his work, stand out, and which gives it that haunting

impact that’s uniquely his. Thomas Mann, writing of Freud, said that when a

writer has acquired:

"... the habit

of regarding life as mythical and typical there comes a curious heightening of

his artistic temper, a new refreshment to his perceiving and shaping powers,

which otherwise occurs much later in life; for while in the life of the human

race the mythical is an early and primitive stage, in the life of the

individual it is a late and mature one. What is gained is an insight into the

higher truth depicted in the actual; a smiling knowledge of the eternal, the

ever-being and authentic..." [27]

This brings us to the nub of the problem.

Moving film inherited much from its origins in photography and matured at a

period when realism was the dominant mode. When putting his fiction on screen

the temptation is seldom resisted to take Dickens out of his own world of dream,

fantasy and to recreate the Dickens world in terms of this historically much

later tradition of social realism. This is certainly the case with David Lean’s

Great Expectations 1946 and Oliver Twist 1947[28].

But a consideration of this argument illuminates some interesting tensions. The

fact is, that however fantastic, grotesque and dreamlike his fiction is, we

nevertheless sense that it is firmly rooted in the realities of the world we

all know and recognize. That is part of the mystery (and the power) of Dickens.[29]

(I think this might well be true of our dreams too). And indeed there are

sometimes clearly and definite historical connections. Nicholas Nickleby

is a particularly interesting case in this respect.

Uncle Ralph Nickleby is striking example.

Yes, on the surface there are obvious parallels with Scrooge and the pantomime

wicked uncle. Ralph is

selfish, miserly and materialistic. But he represents values that contemporary

readers would recognise. Uncle Ralph is a figure of the modern world. He does

not own land. He does not farm. He does not, apparently, actually work. He

makes nothing. Except money. He is a

dealer, a chancer, a speculator and a swindler. Money was in the air. Britain

was in the grip of vast social developments and chances probably not

comprehended at the time, but certainly felt. The traditional land owning,

aristocratic dominated social hierarchical system of social control was

apparently crumbling. The tidal wave of pressure for parliamentary reform that

was the climax in the passing of the Reform Act in 1832 (Dickens was a reporter

in the House during its passage) coupled with the changes in trade, commerce

and manufacture that gave us a new rising middle class, seemed to threaten the

very fabric of society. Money assumed a new significance and seemed likely to

eclipse social class. Mr Dombey, a rich merchant who has made his money

through trade, is described as a financial Duke of York”

And we note that

Uncle Ralph swindles his aristocratic friends. An awareness of these social

tensions informs David Edgar’s celebrated Royal Shakespeare version of Nicholas

Nickleby. As David Edgar commented on the sense of undefined loss that lay

behind the excitement and opportunities of the times:

The old

certainties…were dissolving. Hundreds of thousands were crowding into the

cities, where the old rules seemed no longer to apply. True, the out-moded

hierarchies and snobberies were swept away by the winds of change; but

something else had gone too: the idea of a social hierarchy which not only

granted immeasurable rights to the powerful, but imposed obligations on them

too…”[30]

And he went on to

quote Marx and Engels:

The

bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal,

patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley

feudal ties that bound man to his ‘natural superiors’ and has left remaining no

other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash

payment’… The bourgeoisie has torn away from the family its sentimental veil,

and has reduced the family relation to a mere money relation… All fixed,

fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and

opinions are swept away, all new formed ones become antiquated before they can

ossify. Al that is solid melts into air, all that is wholly is profaned, and

man is at last compelled to face, with sober senses, his real conditions of

life and his relations with his kind”. [31]

Uncle Ralph

Nickleby is very much a man of his moment, a man created in the shadow of the

Reform Act and its consequences.

The First

Reform Bill and Its Consequences

A series of

economic, social and political changes following the end of the Napoleonic wars

seem to reach a peak in the campaign for and the passing of the First Reform

Bill in 1832. Changes and disturbances in social stability had manifested

themselves in the British class system that had survived for so many centuries.

To many at the time, especially those in the top layers of the social

structure, it seemed as if social barriers that had protected their position

over the centuries were in danger of being breached by pushy middle classes and

even those below them. The traditional system based on the ownership of land

that had maintained the social hierarchy was yielding place to the new classes

who thrived economically from banking, manufacture, trade and commerce. Many

had been enriched in the profits made from recent the wars. Many were enriched

from overseas trade. Many thrived in the industrial revolution. David Ricardo

in Principles of Political Economy and Taxation 1817 characterizes the

tradition social system and its sense of order. The

aristocracy was rent takers; middle classes were profit takers and the working

class was wage earners. Class was related to market position, and therefore

involved privileges in education as well as property; class status involved

recognition by others in social status or social honour”. Throughout the early

19th century there is that sense of an old, traditional way of life

or society” in a state of disintegration and collapse, being replaced by an as

yet unformed but rapidly forming New Social Order. The engine of these changes

was industrial production that was replacing the traditional land based

economy. Ralph is one of the

bubbles of this economic activity and effervescence -- a speculator and

swindler of a kind that thrived in the particular economic context of the mid

1830s and early 1840s[32].

This was a period of short-term fluctuations with peaks of business activity in

1836 and 1839-40. [33]

Some economic historians see the years 1838-2 as totally depressive years, [34]

there had been a boom in trade in 1825, which in turn was followed by a

financial crisis. There were then seven years of dull trade figures, although

in 1828 and the first part of 1831 there were signs of a revival in trade. The

signs quickened and this strong upward trend brought a boom in 1836. This was a

year of speculative mania. The President of the Board of Trade, J. Poulett

Thomson, in as speech in the Commons in May 1836 said that it was impossible

not to be struck with the spirit of speculation which then existed in the

country: I felt it my duty to direct a registry to be kept…of the different

joint stock companies and the nominal capital it was proposed to embark in

them. The nominal capital to be raised by subscription amounts to £200,000,000

and the number of companies in between 300 and 400. I am just now reminded of

the speculation for making beet sugar, but that is a sound speculation compared

with some on my list. The first is the British Agricultural Loan Company with a

capital of £2,00,000… Another is proposed for supplying pure spring water,

capital ££30,000… The Safety Cabriolet Company, capital £100,000; the British

and American Intercourse Company, capital £2,000,000… I fear that the place I

represent (Manchester) can furnish instances of schemes … that can never be

beneficial to anyone. The fact is speculators for the purpose of selling their

shares get up the greater part of these companies. They bring up their shares

to a premium, and then sell them, leaving the unfortunate purchasers … to shift

for themselves”.[35]

This immediately

brings Ralph Nickleby and the United Metropolitan Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking

Company to mind to mind. Mr And Mrs Nickleby discussed how to repair their

capital after its decline following the education of Nicholas and Kate. Mrs

Nickleby’s advice to her husband is Speculate with it…. Think of your

brother; would be what he is, if he hadn’t speculated?” Dickens’s comment is obviously made with the

immediate economic context in mind: Speculation is a round game; the

players see little or nothing of their cards at first starting; gains maybe

great – and so may losses. The run of luck went against Mr Nickleby; a mania

prevailed; a bubble burst, four stockbrokers took villas in residences at

Florence, four hundred nobodies were ruined, and among them Mr Nickleby”.

(Nicholas Nickleby, Chapter 1).

In McGrath’s

screenplay, the main thrust of these sentiments appears in the dialogue when

Uncle Ralph receives Mrs Nickleby, Nicholas and Kate, to discuss what might be

done to help them. But its superb accuracy is inevitably muffled. The relevance

is driven home in the scene immediately preceding Ralph’s interview with his

impoverished country relatives.

Ralph is in his

office and receives a visit from one of his fellow speculators, Mr Bonney. He

comes to tell him that their latest scam is about to be launched:

…. there’s not

a moment to lose; I have a cab at the door. Sir Matthew Pupker takes the chair,

and three members of Parliament are positively coming…. It’s the finest idea

that was ever started. ‘United Metropolitan Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking and

Punctual Delivery Company. Capital, five millions, in five hundred thousand

shares of ten pounds each’. Why, the very name will get the shares up to a

premium in ten days”. (Nicholas Nickleby, Chapter 2).

In the

conspiratorial badinage that follows we learn that Ralph is recognised an

experienced manipulator who gets the investments to peak and knows the right

time to sell and back away. Recourse to the historical evidence shows that this

was characteristic of the times. The damaging effects of this speculative mania

frightened investors and led to a period of gloom until 1842. Company law was

at this time underdeveloped.

The Select

Committee on Joint Stock Companies, investing corruption in the markets,

reporting in 1844, found that there were three basic kinds of company:

(a)

Bona fide

companies, which were commercially foolish.

(b)

Bona fide

companies which were badly managed, and therefore open to twisters and frauds.

(c)

Totally

fraudulent companies.[36]

We are doing more

than translating it from one language to another We are also trying to fashion

it into a product that be enjoyed by the modern public who may well not be

aware of this historical context. The results are interesting, for Uncle Ralph

as played by Christopher Plummer becomes a more mythical, archetypal, indeed

almost the pantomime Wicked Uncle, swindler and skinflint. The transformation

works well, due in much part to Christopher Plummer’s subtle but menacing

creation of the role.

Then there’s the

way in which Ralph tries to help” Kate Nickleby. In the novel he suggests that

Kate seeks employment with Mrs Mantelini, the milliner. The real meaning of

this, that Dickens’s readers would understand immediately, is probably lost to

modern readers. Milliners shops were notoriously where gentlemen picked up

prostitutes. Milliner’s apprentices frequently supplemented their modest income

with this additional trade.

Prostitution,

endemic in London, Dickens had found deeply shocking since he got to know the

ins and outs of this great, sprawling city. The Commissioner of Police deposed

to the Society for the Suppression of Vice that in London there were 7,000

prostitutes, 933 brothels and 848 other "disreputable houses" -- the

tone of his evidence was that his officers were doing a good job in suppressing

vice. Other sources suggest this was a conservative estimate, and that there

were more like 80,000, who entertained 2,000,000 clients a week (an estimated

twenty-five per girl). [37]Dickens’s

fiction is full of the terrors of the vice trade -- from Nancy in Oliver

Twist onwards -- not always obvious to modern readers, but the clues are

there. An awareness of this makes one realize the sinister import of what Ralph

says: Dress-makers in London, as I need not remind you, ma'am, who are so

well acquainted with all matters in the ordinary routine of life, make large

fortunes, keep equipages, and become persons of great wealth and fortune...”.

Mrs Nickleby is

too unworldly to realize that "milliner" was more or less a

euphemism for prostitute. Readers of Nicholas

Nickleby in the late 1830's would comprehend the hints from the

descriptions of Madame Mantalini's premises, and the behaviour of Sir Mulberry

Hawk. [38]

An audience today may not specifically apprehend the real villainy in Uncle

Ralph’s proposals for his young fourteen year-old niece, but they will respond

with disgust at Sir Mulberry Hawk’s vile and suggestive behaviour.

Then there is

the case of Wackford Squeers. This refers to the Yorkshire Schools”

scandal of Dickens’s day, and to the notorious case of William Shaw, headmaster

of Bowes Academy in Greta Bridge, whom Dickens met when he travelled with his

illustrator Hablot Brown (Phiz”) to Yorkshire in January 1838 while

researching Yorkshire Schools for this novel.[39]

The novelist claimed that as a child he’d learned about these institutions

that, in coaching days, were safely remote from the metropolis and had the

added advantage of charging no extras and having no vacations. [40]

Social indiscretions and unwanted children could be safely stowed away, out of

sight and in most cases out of mind. (Conversation between Squeers and Snawley

in Nicholas Nickleby, Chapter 4).

A Yorkshireman

Dickens warned him to have nothing to do with Shaw. This was the original of

John Browdie.[41] Shaw had

been prosecuted in 1823 by the parents of two children who went blind while in

his care at Bowes Academy. Dickens hoped to infiltrate Bowes Academy by posing

as the friend of a widow who had a son she could not look after. Shaw was

suspicious and reluctant to show Dickens round. But they looked around the

village. Between 1810 and 1834 twenty-five boys from the school between the

ages of seven to eighteen had been buried in the local graveyard. Dickens also

inspected schools at Barnard Castle and Startforth.[42]

The novelist used evidence from the court proceedings when writing the terrible

sections on Dotheboys Hall. Boys testified that there were nearly hundred boys

at the school, that they had meat” three times a week that was crawling

with maggots and bread and cheese the rest of the time. They had no supper

except warm water and milk and dry bread for tea. They all had to wash in a

trough. The boys slept on straw with one sheet to each flea-infested bed, in

which four or five boys slept together. Boys were frequently and brutally

trashed. It was revealed that ten children had gone blind at the school as a

result of malnutrition and ill treatment.

One of Shaw’s

pupils testified: ”On one occasion I felt a weakness in my eyes, and could

not write my copy; the defendant said he would beat me; next day, I could not

see at all, and told Mr Shaw, who sent me, with three others, to the

wash-house, as he had no doctor; those who were totally blind were sent into a

room; there were nine boys in this room who were totally blind…” The boy

who gave this evidence in court was totally blind. Another boy testified that

when anybody came to visit the school, Shaw used to order the boys who had no

trousers or jackets to get under the desks”. Soap and towels were rare.

William Shaw was fined £500 but continued to run his school.

The similarities

are very close. Like his counterpart, Squeers, Shaw had only one eye. Shaw’s

cards stated his school was near Greta Bridge, just as Dotheboys Hall cards

did, and went on to claim the school to teach young gentlemen Latin,

English, arithmetic, geography and geometry, and to board and lodge them for

£20”. These, too, are Squeers’s terms. Shaw’s advertisements also said the

school party left from the Saracen’s Head, Snow Hill, just as in Nicholas

Nickleby. [43] And, by the

way, cinema goers will get the impression from this film that in those days

traveling by stage coach was rather like using a taxi today, as the coach takes

Squeers and the boys right to the very gates of Dotheboys Hall. A stagecoach

journey from London would have delivered passengers to the nearest city and

they’d have to make their own way from there. (In today’s Britain, we don’t

even have a decent bus service!)

Dickens’s

writing here was thus firmly rooted in realities. But those realities have now

gone. Such institutions have disappeared long ago, and yet the scenes at

Dotheboys Hall continue to make an impact upon the imagination because they

have passed beyond the factual reforming propaganda originally intended and

into the realms of the archetypal and mythological, symbolically representing

for all time the barbaric authoritarian treatment of the young and helpless. As

Edgar Johnson comments: …the propaganda novel…. gained tremendously in

vividness through being embodies in concrete details. The eye of the reporter

could sharply note the facts, the novelist’s imagination transform them from

statistics into a symbol dyed in emotion”. [44]

Take, for example, the scene where Smike, having been recaptured after his

escape from Dotheboys Hall, is brought back to be thrashed in front of the

school by Squeers. Dickens’s portrayal of this passes beyond melodrama and into

myth. We have all dreamed of seeing school teacher-tormenters being themselves

tormented.

There is a

dream-like sense in the scene. It seems as if an avenging angel symbolically

punishes Squeers. The boys moved not hand or foot” as Squeers’s son and

daughter do their best to inflict damage and Mrs Squeers tries to drag

Nicholas off the suffering tyrant as he beats the ruffian till he roared

for mercy”. Nicholas feels the blows as if they had been dealt with

feathers. Matters are dealt with here in much the same way as retribution is

visited upon villains in fairy stories. Nicholas himself feels transplanted

briefly into another world, beyond everyday realities. Dickens writes that having

brought affairs to this happy termination, and ascertained … that Squeers was

only stunned…” (Nicholas Nickleby, Chapter 13). He then reflects as

to what he should do next. This is not realism. Matters in our world are seldom

resolved in this satisfactory manner. [45]

Thus the treatment of several leading characters and

situations is usually convincing and successfully carries over Dickens’s

intentions.

The Sense

of Style

In the larger

understanding of the concept of style, the overall mis-en-scene, McGrath

does not go for realism. What you see on screen is frankly not convincing, not

credible, as a picture of English life in the 1830s. It looks like a film set.

There is no evidence of any apprehension of life at this period. Cinemagoers

will get the odd impression, for example, that the stagecoach was used much in

the same way as today’s taxi service. We see Squeers and his charges mount the

coach at the Saracen’s Head, and a few (hundred) miles later it deposits them

right at the very gate of Dotheboys Hall. Such a journey by stagecoach at this

period would take about four days, with stops at Huntingdon, Stamford and York.

Establishments such as Dotheboys Hall flourished because they were so

inaccessible, so remote from the south of England. They were destroyed not so

much by Dickens’s satire in Nicholas Nickleby as by the coming of the

railways[46]. The

travelers to Squeers’s academy would somehow have to make their own way from

York to the school. Landscape and rural scenes are characterized by

unconvincing greetings card prettiness very much in the style of populist

consumerism, looking as it does, much like supermarket food packaging. One

thinks particularly of dairy and bakery products.

Nicholas Nickleby

and London

The attempt to

recreate the sense of London” is singularly inadequate. This is hard to

forgive. If any writer had London coursing his veins, that writer was Charles

Dickens. And the novelist uses a particular sense of London to colour or

orchestrate Nicholas Nickleby.

When Dickens was

ten, John Dickens was transferred to London and the family lived at Bayham

Street Camden Town. In October 1823 the family moved to Gower Street North. The

boy took to wandering about the streets of Camden and Kentish Town, even

getting as far as Holborn and the City. He gained satisfaction simply from

wandering and observing the multiplicity of activities -- people, shops,

businesses, traffic, warehouses, counting-houses, dock-buildings, shipyards,

taverns, theatres, archways, sailors' homes, ship-breakers' yards, second-hand

clothes dealers', cook-shops, doss-houses, courts, alleys, little squares,

timber-sheds, pawnshops, chandlers -- which made up life in the metropolis.

This was a habit that was to remain with him for the rest of his life[47].

Dickens thus gained an extensive and peculiar knowledge of London that

powerfully informs and enlivens (or darkens) so much of his fiction. His

knowledge of London would certainly have equaled that of the immortal Micawber,

who assures the naïve David Copperfield that he can guide him to safety to his

lodging:

Under the

impression … that your peregrinations in this metropolis have not as yet been

extensive, and that you might have some difficulty in penetrating the arcane of

the Modern Babylon in the direction of the City Road – in short --- that you

might lose yourself – I shall be happy to call this evening and install you in

the knowledge of the nearest way”. (David Copperfield, Chapter 11).

He was clearly fascinated by the contrasts of busy

metropolitan life, where the riches of the world were displayed amid the

grimmest poverty:

.... Emporiums of splendid dresses, the

materials brought from every quarter of the world; tempting stores of

everything to stimulate and pamper the sated appetite and give new relish to

the oft-repeated feast; vessels of burnished gold and silver, wrought into

every exquisite form of vase and dish, and goblet; guns, swords, pistols, and

patent engines of destruction; screws and irons for the crooked, clothes for

the newly-born, drugs for the sick, coffins for the dead, churchyards for the

buried -- all these each jumbled with the other and flocking side by

side....The rags of the squalid ballad-singer fluttered in the rich light that

showed the goldsmith's treasures; pale and pinched-faces hovered about the

windows where was tempting food; hungry

eyes wandered over the profusion guarded by one thin sheet of brittle glass --

an iron wall to them; half-naked shivering figures stopped to gaze at Chinese

shawls and golden stuffs of India. There was a christening party at the largest

coffin-maker's, and a funeral hatchment had stopped some great improvements in

the bravest mansion. Life and death went hand in hand; wealth and poverty stood

side by side; repletion and starvation laid them down together. But it was

London..... (Nicholas Nickleby Chapter 32)

Dickens is of course the great poet of London. Whether

he adopted London, or London adopted him, is no matter. The dark, bright,

sleeping, animated, restful, bustling metropolis seemed to flow in his veins. I

believe that his ideas about London and city life we gradually coming together

at the time he was writing Nicholas Nickleby, and they were to develop

depth and complexity in his subsequent work. Dickens

was the first major novelist to take modern industrial city life as his basic

material. He doesn’t use the cityscape as a background for the narrative; it is

more to the point to say that his fiction is actually about the modern city. No

other classical novelist has so consistently portrayed modern city life like

him.

Early in his

career commented on the faceless, anonymous quality of city life that resulted

from the crowding together of masses of people together in cities more or less

required by the modern economy and particularly by the factory system. In 'Thoughts

About People' in Sketches by Boz the young Dickens wrote:

"'Tis

strange with how little notice, good, bad or indifferent, a man may live and

die in London. He awakens no sympathy in the breast of any single person; his

existence is a matter of interest to no one but himself, and he cannot be said

to be forgotten when he dies, for no one remembered him when he was

alive..."

When Mr

Pickwick gets up on the first morning of his immortal travels, he looks out of

his window:

"....upon

the world beneath. Goswell Street was at his feet, Goswell Street was on his

right hand, as far as the eye could reach, Goswell Street extended on his left;

and the opposite side of Goswell Street was over the way..."

He knew this

area well as the Dickens family lodged at 4 Gower Street North, Bloomsbury,

1823-4. It was here that Dickens’s mother unsuccessfully attempted to open a

school for young ladies. When Oliver Twist is taken through London by Sikes

before the robbery, his impressions are of some place like hell on earth --

vacuous bustle, murk, anonymity, noise, smoke, a tumult of discordant sounds:

"It was

market-morning. The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire;

and a thick steam, perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle, and

mingling with the fog, which seemed to rest upon the chimney-tops, hung heavily

above. .... Countrymen, butchers, drovers, hawkers, boys, thieves, idlers, and

vagabonds of every low grade, were mingled together in a dense mass...."

The scene

confounds his senses because of the infernal mixture of:

"....the

whistling of drovers, the barking of dogs, the bellowing and plunging of oxen,

the bleating of sheep, the grunting and squeaking of pigs; the cries of

hawkers, the shouts, oaths, and quarreling on all sides; the ringing of bells

and roar of voices, that issued from every public house; the crowding, pushing,

driving, beating, whooping and yelling; the hideous and discordant din that

resounded from every corner of the market; and the unwashed, unshaven, squalid,

and dirty figures constantly running to and fro, and bursting in and out of the

throng...."

Little Nell and

her grandfather watch the crowded streets in the Midlands:

"The throng

of people hurried by, in two opposite streams, with no symptom of cessation or

exhaustion; intent upon their own affairs; and undisturbed in their business

speculations, by the roar of carts and wagons.... the two poor strangers,

stunned and bewildered by the hurry they beheld but had no part in, looked

mournfully on; feeling amidst the crowd a solitude which has no parallel but in

the thirst of the shipwrecked mariner, who, tossed to and fro upon the billows

of a mighty ocean, his red eyes blinded by looking on the water which hems in

on every side, has not one drop to cool his burning tongue".

Long before the

major satires of Bleak House and Little Dorrit, the idea of

loneliness in the midst of the crowded city, of human anonymity, had been a

leading theme in Dickens work. There are the stories 'Nobody's Story', 'Somerbody's

Luggage' in The Christmas Stories, and the original title of Little

Dorrit had been Nobody's Fault. Nobody's Story concludes:

"If you

were ever in the Belgian villages near the field of Waterloo, you will have

seen in some quiet little church, a monument erected by the faithful companions

in arms to the memory of Colonel A, Major B, Captains C, D and E, Lieutenants F

and G, Ensigns H, I and J, seven non-commissioned officers, and one hundred and

thirty who fell in the discharge of their duty... The story of Nobody is the

story of the rank and file of the earth. They bear their share of the battle;

they have their part in the victory; they fall; they leave no name but in the

mass...." ('Nobody's Story', Christmas

number of Household Words, 1853).

In discussing

the effects of the Crimean War on the British people, Dickens referred to:

"We, the

million, who have no individuality as a million, or as a corporation, or as a

regiment, though as Mr A, or my Lord B, or Alderman C, or Private D, we each

may suffer, and have our private griefs; we the Nobody Everybody, to whom

nothing is anything to speak of...." (Household

Words, volume ix 1854)

In his Life

of Charles Dickens 1872, John Forster refers to ideas the novelist recorded

in his notebook, which might make the basis for development. Among them he

recorded "a fancy that savours of the same mood of discontent political

and social" as John Forster commented. Charles Dickens wrote:

"How do I

know that I, a man, am to learn from insects -- unless it is to learn how

little my littlenesses are? All that botheration in the hive about the queen

bee, may be, in little, me and the Court Circular".

And another

idea:

"English

landscape. The beautiful prospect, trim fields, clipped hedges, everything so

neat and orderly, gardens, houses, roads. Where are the people who do all this?

There must be a great many of them, to do it. Where are they all? And are they,

too, so well kept and fair to see?" (Life of

Charles Dickens, Book IX, Chapter vii)

Dickens is

recording the same symptoms noted by Friedrich Engels. Modern industrial,

commercial, city life crowded the striving together into a battle of life and

death in which their common humanity was sacrificed as the strife was not only:

"...

between the different classes of society, but also between the individual

members of these classes. Each is in the way of the other, and each seeks to

crowd out all who are in his way. The workers are in constant competition among

themselves as the members of the bourgeois among themselves..."[48]

Figures to

support the Dickensian image of the crowded city as the centre of action in the

novels are impressive. Throughout the period of Dickens's life the population

not only increased, but also concentrated itself in towns. London grew from

1,117,000 in 1801 to 1,600,000 in 1821 and by 1841 (the year of The Old

Curiosity Shop) had reached 2,239,000 -- it had more than doubled. In the same

period Manchester grew from 75,000 to 252,000 (nearly trebled). Bradford grew

from 13,000 to 67,000. Birmingham from 71,000 to 202,00. Glasgow from 77,000 to

287,000, Liverpool 82,000 to 299,000. By 1861 Manchester reached 399,000 and

Birmingham 351,000.[49]

The marvel of the nation's economic greatness, Engels proposed in the 1840's

was really human sacrifice:

"After

roaming the streets of the capital for day or two, making headway with

difficulty through the human turmoil.... After visiting the slums of the

metropolis, one realizes for the first time that these Londoners have been

forced to sacrifice the best qualities of their human nature... The very

turmoil of the streets has something against which human nature rebels. The

hundreds of thousands of all classes...crowding past one another, are they not

all human beings.... with the same interest in being happy? And still they

crowd by one another as though they had nothing in common...." [50]

As Frederic

Schwarzbach argues (Dickens and the City 1979), Dickens's fiction plays

an important part in the way we perceive the cultural impact of the growth of

urban living. As Walter Bagehot remarked, Dickens described the city like

"a special correspondent for posterity". Dickens certainly

reflected consensus of enlightened public opinion, but had himself moved from

the country to the town at a time when it was a typical experience of the

British -- by 1851 only 49% of the population lived in the country -- and in

the notorious blacking factory experience he personally had childhood

experience of industry. He’d personally experienced the great change from life

in a mainly rural economy to industrial and commercial city squalor. Frederic

Schwarzbach argues that he created a myth of city life, still resonant

in our culture, by means of which to explore and evaluate this new experience.

This is strong in Nicholas Nickleby and I was disappointed that it has

been so feebly presented in this film. The rural scenes are just not

convincing. I was almost moved to laughter at the depiction of the country

landscape where we were to suppose the Nickleby family had lived before the

death of the head of the family threw them at the mercy of Uncle Ralph.

Even though we

have to admit Dickens's obvious love of the convivial and companionable

qualities of town life (he missed the streets of London, vital to the

stimulation of his imagination, when he was abroad) we may perceive a mythic

structure in the famous autobiographical fragment which he wrote for John

Forster -- childhood/country/paradise as against adult-life/city/hell. We are

looking at the myth of the fall from a lost rural paradise into the urban hell

of infernal city. The myth is fairly powerful in British ideology. Few have

escape the Leavisite doctrine along with its maypoles, mummery, corn dollies,

Cotswold cottages and all that Lark Rise to Candleford flummery that

constitutes the theory of the organic community. Dickens then, is writing in a tradition, which stretches back to

Hesiod and forward to Emmerdale Farm.

This is not a

theme developed in the later "serious" novels. It we find it

everywhere. In the chapter on the Hampton Races in Nicholas Nickleby he

describes the grubby but glowing and cheerful faces of the gipsy children at

the races, and underlines the contrast between these children of nature, and

the maimed children of modern industrialized society:

"It was one

of those scenes of life and animation, caught in its very brightest and

freshest moment, which scarcely fail to please; for if the eye be tired of show

and glare, or the ear be weary with a ceaseless round of noise, the one may

repose, turn almost where it will, on eager, happy, and expectant faces....

Even the sunburnt faces of gipsy children... suggest a drop of comfort. It is a

pleasing thing to see the sun has been there; to know that the air and light

are on them every day; to feel that they are children and lead children's

lives; that if their pillows be damp, it is with the dews of Heaven, and not

with tears; that the limbs of their girls are free, and that they are not

crippled by distortions, imposing an unnatural and horrible penance upon their

sex; that their lives are spent from day to day at least among the waving

trees, and not in the midst of dreadful engines which make young children

old before they know what childhood is,

and give them the exhaustion and infirmity of age, without, like age, the

privilege to die...."(Nicholas Nickleby Chapter

50)

He wrote to John

Forster from Broadstairs on 16 August 1841:

"I sit down

to write to you without an atom of news to communicate. Yes, I have something

that will surprise you, who are pent up in dark and dismal

Lincoln's-Inn-fields. It is the brightest day you ever saw. The sun is

sparkling on the water so that I can hardly bear to look at it. The tide is in,

and the fishing boats are dancing like mad. Upon the green-topped cliffs the

corn is cut and piled in shocks; and thousands of butterflies are fluttering

about...."

The sense of

London is strong in Nicholas Nickleby and Dickens uses the qualities of

particular London locations analogously to body forth man’s inhumanity to man