Soft Soaping Dickens:

Andrew Davies, BBC-1, and Bleak House

By Robert Giddings, Professor Emeritus, School of Media Arts and Communication, Bournemouth University

Reprinted with the kind permission of the author

Published on this site July 26, 2005

'The runaway success of Harry Potter is rewriting the record books. But one of the greatest revolutions in publishing came more than 150 years ago, from the pen of... Charles Dickens...His works - including A Christmas Carol and Oliver Twist - were serialized in weekly or monthly parts and have been described as the soap operas of their day...'

Bleak House (2005) DVD

Gillian Anderson, Anna Maxwell Martin, Denis Lawson

So, this is Andrew Davies's first dramatization of a full Dickens novel: "I never really thought of myself as a Dickensian", he told me: "I never really thrilled to him in school, and at university in the fifties, I was rather under Leavis's spell. He didn't have much time for Dickens, except 'Hard Times'. In my thirties I realised how wrong Leavis was. Read a lot of Dickens - my favourites were 'Little Dorrit' and 'Our Mutual Friend'. But I always had reservations. I was never quite sure about the manic exuberance of his comic characters; and I was quite sure I didn't like the insipid sentimentality in the characterisation of his heroines". [3]

Nevertheless, Davies is excellently qualified to translate Dickens's early masterpiece to the small screen. He knows how a novel works - a Leavisite education and years of teaching experience have seen to that - and he's a very experienced writer - novels, plays and radio and television dramas. He is the acknowledged master at turning prose fiction into TV drama, classics as well as modern novels. When he more or less single-handedly revived the classic serial with Middlemarch and Pride and Prejudice he demonstrated the art of translating fiction into the language of television -- not so much continuing literature by other means, as using literary works to create television drama.

He said that he'd enjoyed doing Dickens's The Signalman, (BBC, Christmas 1976):

"That was a delightful experience. But I was never offered the chance of adapting one of the big novels, and I was quite happy to enjoy the work of others - notably the 1970s dramatisation of 'Our Mutual Friend' - I enjoyed the more recent one too - and the 1982 'Bleak House', which really set a new standard for the genre, to my mind".[4]

He was hesitant when Jane Tranter, BBC TV Head of Drama, suggested Bleak House to him: "Arthur Hopcraft's fine adaptation was still very fresh and vivid in my mind, and I wasn't at all sure that I could better, or even equal, his achievement. But it was a great challenge and a great opportunity, and I accepted it, albeit with some trepidation". [5]

Davies has worked with producer Nigel Stafford-Clark before, on Trollope's The Way We Live Now and He Knew He was Right. BBC-1's new Bleak House is a completely new way of doing Dickens on the small screen - half hour episodes, shown twice a week. A fair amount has been surgically removed and the dual narrative recast a straightforward story line:

"No one had a particular vision of the book at the outset, but the BBC were keen that this new adaptation should feel new, be bold and different in execution. I talked about all this with Nigel Stafford-Clark, the producer -- it was brilliant Nigel who came up with the idea of adapting it in a large number of half-hour episodes, hopefully capturing something of the excitement of the original serial publication. This idea was enthusiastically received, and developed into the notion that the show might go out twice a week after 'EastEnders' and try to capture some of that audience, and also a younger audience than the usual classic serial audience". [6]

Inevitably, the publicity banged on about Dickens really writing Victorian soap operas. Andrew Davies himself rather rashly opined: "If Dickens was alive today, he'd be writing for 'EastEnders'"). Was this version planned as a soap?

"We didn't follow Dickens's own chapter endings, though we paid close attention to them. When we story-lined the book we were looking for cliffhanger endings to as many episodes as possible. The original aim was to do it in twenty episodes. In the course of writing it tightened to sixteen - but that's still eight solid hours of Dickens - much longer than any recent classic adaptations". [7]

In Britain today there is an obvious populist imperative in the production and consumption of culture. Broadsheet newspapers and journals, arts programmes on television and radio, regularly give extensive coverage not only to Wagner, Ibsen, literary novels, art house films, exhibitions of old masters and all that; but to rock and pop music and blockbuster movies. The death of disk jockey John Peel last year almost gave rise to a day of national mourning that reminded me almost of the death of Princess Diana. And there is even serious talk of establishing a national John Peel Day. In this climate, it was to be anticipated that the media would seize on the chance to discuss Andrew Davies's Bleak House as an example of Volkskultur, soap opera.

There was something rather soapy about BBC-1's new Bleak House, directed by Justin Chadwick (EastEnders and Spooks) and Susanna White (Teachers and Mr Harvey Lights a Candle). It featured what media publicity will always term a galaxy of stars -- Denis Lawson (Holby City); Charlie Brooks (EastEnders) and Gillian Anderson (X Files); such television stalwarts as Timothy West, Warren Clarke, Alun Armstrong, Pauline Collins, Charles Dance, Philip Davies and Richard Griffiths, and also features Anna Maxwell-Martin (a sensational hit in the National Theatre staging of His Dark Materials and convincing Daphne in Radio 4's Jewel in the Crown) as well an array of actors familiar from popular television series -- Alistair McGowan (Big Impression), Richard Harrington (Spooks), Anne Reid (Coronation Street, Dinner Ladies), Matthew Kelly (Stars in Their Eyes), Nathaniel Parker (Inspector Lynley Mysteries), Hugo Speer (The Rotters Club and The Full Monty, film), Liza Tarbuck (Linda Grant), Roberta Taylor (The Bill, EastEnders) and Johnny Vegas and all, and all.BBC publicity was blatant and consistent in the Dickens-wrote-soap-operas claim. In June 2003 Matthew Davis of BBC News was already telling us:

"The runaway success of Harry Potter is rewriting the record books. But one of the greatest revolutions in publishing came more than 150 years ago, from the pen of ... Charles Dickens...His works - including A Christmas Carol and Oliver Twist - were serialized in weekly or monthly parts and have been described as the soap operas of their day..."

"Bleak House Gets the Soap Opera Treatment for BBC-1" screams the headline of the Press Release and Press Pack, (19 May 2005) and goes on:

"Writer Andrew Davies, who delighted audiences with his adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, is turning Charles Dickens's 'Bleak House' into a new series of soap-opera style episodes for BBC-1.

Dickens's original readers enjoyed the novels in short instalments which ended in cliff-hangers to persuade them to buy the next chapter.

Laura Mackie, BBC Head of Drama Serials, was reported as saying: 'It's a new way of doing the classic adaptation, reinvigorating our approach to the serial form, matching it to the serial structure and narrative development of the original - and the way that it was originally published.

The Dickens novel was very much the soap opera of its day..."

Owen Gibson, of the Guardian, reporting BBC Director General Mark Thompson's promise to invest £21 from his controversial plan to cut 6,000 jobs and slash budgets by 15%, said:

"...The boosted investment...will allow more cash for the summer schedule. Drama highlights for the season will include Dickens's 'Bleak House', adapted by Andrew Davies as 'soap opera' half-hour shows, four Shakespeare adaptations and two Stephen Poliakoff films". [8]

And in July, when BBC-1 publicised their Autumn schedules, the Guardian dutifully repeated the populist spin, placing Bleak House as part of a classic/populist package, declaring this "new version of the Charles Dickens classic" that remains "in its original era" (well, that's something for which we may all be thankful) is produced "in the style of a modern-day soap." Other promised goodies were a "big budget version of Robin Hood" and "modern day retelling of four Shakespeare plays with big-name writers and all-star casts".[9]

The Stage, reported that:

"X-Files star Gillian Anderson has secured a £500,000 deal with the BBC to appear in an adaptation of Charles Dickens's 'Bleak House'. Anderson will play the role of Lady Honoria Dedlock in the costume drama, which the Corporation is billing as high quality with a huge ensemble cast. The show is to air twice a week in the style of a soap opera for total of twenty episodes..." [10]

Nathaniel (Inspector Lynley) Parker, who plays Harold Skimpole in this new dramatization, comments:

"Dickens's style was to write instalments that were published continuously. So one might tend to say that Dickens invented the cliff-hanger to keep his readers interested in his stories and buying them week after week. Andrew Davies is trying to match this serial character of Dickens's novel to the television format. BBC-1 plans to produce this new series as a sort of soap opera, which sounds very interesting to me..."[11]

It has been interesting to note that some heavyweight media pundits in due course took up these claims. Peter Preston, distinguished political journalist[12], in October 2005, for example expressed his views on these additional literary career potential of our greatest novelist, confidently asserting: "He would be churning out scripts for television, according to Andrew Davies, adaptor ubiquitous, because he was a compulsive storyteller. He would be writing soaps or near-soaps week by week, just as he wrote some of his greatest books for magazines chapter by chapter. He might he even be the resident genius behind Coronation Street..."[13]

From an early stage it was planned that Bleak House was to be transmitted immediately following EastEnders, the aim was to pull in a younger audience, not normally expected to watch a classic novel on the small screen. Andrew Davies commented:

"The heart of the story is a group of young people starting out in life, discovering themselves and what life holds for them, and I've tried to make the adaptation lively and accessible for viewers of all ages". [14]

Interestingly enough, Andrew Davies was not well disposed to the tendency of casting soap stars and popular actors to pull in viewers. He said:

"I deplore the increasing tendency for the producer and director to be overruled by those higher up the food chain, with their anxiety to have "names" readily recognisable to the soap-viewing public in order to secure high audience ratings. I preferred the days when television created stars, rather than recycling them. But having said that, Nigel and his director, Justin Chadwick, have fought tigerishly to defend the integrity of the casting, and we're also fortunate that a lot of the principal characters in 'Bleak House' are very young, so we have fresh faces playing Esther, Ada, Richard, Guppy, Caddy, Charley..."[15]

Can this Dickens/soap opera thing be taken seriously? Post Modernism obliges us to pay due regard to popular/populist entertainment and many cultural opinion leaders do their duty. Sir John Betjeman, was among a few writers who affected to love Coronation Street before it all became de rigeur. The late Poet Laureate compared went so far as to compare Coronation Street to Pickwick Papers. He declared ecstatically:

"Manchester produces what is to me the 'Pickwick Papers'. That is to say, 'Coronation Street'. Mondays and Wednesdays, I live for them. Thank God, half past seven tonight I shall be in paradise...." [16]

Alan Bennett, too, adores this soap and carried a torch for Hilda Ogden.[17]

Nevertheless, the assertion that Dickens's novels are soap operas and that nowadays he'd be writing TV soaps is flippant. Several quite basic questions need to be asked.

Was this version actually planned as a soap? Andrew Davies told me:

"We didn't follow Dickens's own chapter endings, though we paid close attention to them. When we story-lined the book we were looking for cliffhanger endings to as many episodes as possible. The original aim was to do it in twenty episodes. In the course of writing it tightened to sixteen - but that's still eight solid hours of Dickens - much longer than any recent classic adaptations". [18]

Cutting a classic is always a delicate operation, brain surgery rather than amputation. Andrew Davies found the first half of the book delightful and infuriating in equal measure:

"Dickens seems almost perversely to spawn one group of characters after another, instead of getting on with the story. I look for the spine of the story and try to hang every scene off that spine. The spine of this story has to be Esther's journey of discovery and self-discovery, which is bound up with Lady Dedlock's secret".[19]

So much had to go or was severely trimmed - Mrs Snagsby, the Jellybees, Caddy, Chadbands, Turveydrop -- but these rearrangements were collectively decided by Andrew Davies, Nigel Stafford-Clark, script editors Ellie Wood and Caroline Skinner:

"I had a great deal of help with the plotting...Not too many arguments, though one or two were quite bitterly contested - I wanted Jo's death to be the end of an episode, and would have had it followed by a two minutes' silence if I ruled the BBC, but everyone else wanted Tulkinghorn's death as the episode end, so I had to give way, not very graciously I'm afraid".[20]

Losing Esther's narrative spared a voice over. In Davies's view, this was a distinct advantage:

"Voice-overs sometimes work in first person narratives, but to use an Esther voice over would make it even more difficult to make her appeal to the audience. To most modern readers, Esther's self-regarding, coy, and disingenuous presentation of self is distinctly off-putting, I think. The 1982 version turned her into a droopy plaster saint. I was determined that our Esther would be a bit more spirited. And the book does offer opportunities. Esther is a severely damaged child - she's been told, in so many words, that she's her mother's disgrace, and it would have been better if she had never been born. So she starts the story with a pretty low self-image. But she quite quickly realises that she's useful, intelligent, practical, and has more common sense and judgement than most of those who surround her, even Jarndyce. So I worked on that - her sharp insights, her refusal to be taken in by the Skimpoles of this world, her quickness to see practical solutions, and spiced up her empathetic and loving nature with a bit of spikiness". [21]

Did he feel the loss of Dickens's authorial voice?

"Good question. What's 'Bleak House' without that wonderful opening? But a dramatisation has to be a drama. If first-person voiceovers can sometimes work, third-person voiceovers almost never do. They have a sort of embalming effect, suggesting that everything happened a long time ago and is all safely wrapped up now. Whereas we want the audience to think it's all happening now, vital, urgent, that each moment is a potential point of change. But it is tempting. Sometimes Dickens's own voice is so powerful that you long for the audience to hear it. One stroke of genius in the 1982 version was Hopcraft's inspired idea of putting Dickens's words on the death of Jo into Jarndyce's mouth: 'Dead, your Majesty...and dying thus around us every day!' I couldn't think of anything to equal it, so I included it, as an act of homage to Hopcraft (who died very recently) and, of course, to Dickens himself". [22]

Andrew Davies found the triangle of relationships that bring Ada, Richard and Jarndyce together quite fascinating:

"In the book, Ada has no character at all to speak of - but we decided to build from her affectionate and tactile nature - her love for Richard is a full-on teenage passion, fully reciprocated by him. If Esther learns to trust her own intelligence and judgement, Ada is all instinct, and when the chips are down, she's Richard's girl. The power of young love can be pretty awesome. I think that's what Dickens meant to convey, and it's certainly what I wanted to put over. (Richard, of course, is no problem at all - perfectly realised in the book, his heartbreaking decline is as instantly understandable to a modern audience as it was in Dickens's time.) Jarndyce isn't exactly a problem; rather a fascinating enigma. He's vividly aware of social evils, injustice, and so on, but he doesn't use his wealth and position to combat them, instead preferring small individual life-changing actions, perhaps, as in Esther's case, from dubious motives, conscious or unconscious. Why has he never married? And why does he choose someone so very much younger when he decides it's time to explore his own sexuality? All great material to work with, for the adapter and for the director and actor. Jarndyce's realisation that he has made a mistake, and that he must relinquish Esther, is perhaps the most poignant moment in the story".[23]

Nevertheless, it has always seemed to me that the frequently heard assertion that "Dickens wrote soap operas" is little more than glib media blatherchat. Serial publication was a feature of British publishing in the early Victorian period. Works had been serialized in the previous century. One of Smollett's novels was the first English novel to be published first in serial form.[24] Serial publication had been popular in France since the early 19 th century.[25] These novels were read aloud to families of groups of companions or working colleagues in much the same way as later British serials were consumed.[26]

In Britain, a combination of circumstances led to the growth and development of publishing as an industry, (increased sales reinvested, serial publication underwritten by advertising revenues); including rapid developments in printing technology (movable type, steam press, cheaper wood pulp for paper and eventually, mechanized typesetting); illustrations particularly in serialized fiction, where they helped less literate consumers cope with the stories); publishing (transport (railways expanded markets); growth of popular literacy (Sunday schools and evangelical movement long before 1870 Forster Act); developments in markets and retail outlets (wholesale and retail, W.H. Smith etc., railway bookstalls, shops and markets).[27]

To summarize: the new and ever-increasing reading public that Dickens (and other authors who wrote for the serial market) was created by a combination of factors -- including a considerable increase in population (national population recorded in the 1821 census was 20,983,092. B by 1851 this had grown to 27,533,755) and this was combined with a growth of urban areas as population moved from country into to towns and cities, lured by better employment; an increase in real wages throughout the early Victorian period; investment in railway and transport; wider national/international markets (with minor glitches in the economy); growth of the middle classes, especially lower professional and professional classes; a steady increase in literacy; improvement in transport and postal services and a general awakening of self-improvement -- spiritual, educational and vocational.[28] By the turn of century 97 percent of both sexes able to read.

British book publishing, as we know it today began in this period. Dickens's first novel, the astoundingly successful Pickwick Papers is a key moment in publishing history. It began to appear in monthly serial parts in March 1836. It was a triumph previously unknown in literature, with monthly sales of 40,000. Its method of publication - in monthly parts with advertisements in the parts - rapidly became become standard. Pickwick Papers pioneered this method of publication and established what has now become an accepted method of funding in industrial media practice - advertising revenue.[29] Pickwick's success encouraged Chapman and Hall to publish the book cloth bound in volume form in 1837 after its serial run. As Graham Smith says that this conferred the status of literature on Pickwick Papers "as distinct from the transience of miscellaneous periodical journalism".[30]

Subsequently Dickens ironically commented:

"My friends told me it was a low, cheap form of publication, by which I should ruin all my rising hopes, and how right my friends turned out to be, everybody knows". [31]

Serial publication was a useful way for modestly embarking in publishing with limited capital. Monthly parts could be printed and published, with costs underwritten by including advertising.

In Dickens's case, each monthly part had a separate "Advertiser" section. As artefacts, these serial parts are very interesting socio-economic evidence. Every Dickens novel had green covers. Each novel had an engraved cover that gave some clues as to the contents of the novel. We recognise this today as branding. Punters would always recognise the "new" serial parts of a Dickens novel. It would stand out and identify itself on the booksellers' shelves. It cost a shilling. (Not really cheap, when compared with wages of the day).

Publishing was to become a major industry in the Victorian period -- magazines, newspapers, bibles and religious works, novels, poetry, histories, travels, sporting news, muckraking, sensational publications of all kinds, cheap reference works were all grist to these busy mills. The market was voracious.

Social class (income, education) was a major influence in reading tastes. Drawing on the crude categorization of Matthew Arnold, we can say the well educated but "barbarian" upper class was but a small part of the Victorian reading public. According to Walter Bagehot: "A great part of the 'best' English people keep their minds in a state of decorous dullness." At the lower end of the social scale, Arnold's "populace" was the working-class, with literacy rates were far below the general standard but increasing as working hours diminished, housing improved, and public libraries spread. Consequently, the appetite for cheap publications increased, feeding on a diet of religious tracts, self-help manuals, reprints of classics, penny newspapers, and the expanding range of sensational publications featuring crime, violence, police reports, bawdy ballads etc.

It was Arnold's ever expanding middle class "philistines" that formed the largest reading public for these consumer goods from the publishing industry - both prose and verse -- prose and poetry. And the members of the rapidly developing profession of authorship, of which Dickens was to become such a shining example, supplied this demand. Professional writers regularly supplied uplift, instruction and entertainment for this greedy new market. This was the golden age of the English novel, (but poetry and serious non-fiction also thrived).

Books as purchasable commodities were still rather a luxury in the earlier Victorian period. The industry kept prices high to encourage readers to rent novels and narrative poems from the commercial circulating libraries, these provided a larger and steadier income than individual sales (cf video/DVD today). The system relied on co-operation between writers, publishers and libraries to produce "three deckers," (long novels packaged in three separate volumes) in order to triple rental fees and allowing three readers to consume a single title at one time.

Serial publication provided an alternative lucrative method. In monthly serial parts publication could be underwritten by advertising revenue. This kind of publication thrived from the beginning of Victoria's reign until the 1860s. The evidence is very interesting.

It is not only a matter of considering the nature of the fiction contained in the pages -- the cover price, the style and vocabulary of the writing and the nature of the advertisements tell us a great deal about the intended consumers. It is my firm opinion that Dickens was, in the main, appealing to the lower middle and middling middle classes - the class to which he considered he belonged. The sentiments, ethics and moral attitudes of his fiction are tailor-made for this readership. The language is at the right level.

Advertisements, as with the case of modern commercial television advertising, tell us a great deal about the audience addressed.[32] Dickens's fiction, at the period of Bleak House is full of advertisements for tailor-made clothes; latest fashions for ladies; domestic furniture; equipment for families emigrating to Australia; luxury items for military men and their families; lounging and morning coats, (in tweed, Holland, cashmere, alpaca and Angola "from a guinea"); luxurious shaving and hair preparations (including verses that allude to Jane Austen -- "He thought and thought till on that very day/His powder pride and prejudice gave way").

A quick glance through a random sample of the advertisements that appeared in the monthly serial numbers of Bleak House helps us roughly identify the class of the readership that advertisers believed they would reach. They would seem to have ample disposable income.

Among household goods and furnishings we find:

Mott's New Silver Electro Plate "Possessing in a pre-eminent degree the qualities of Sterling Silver" offers a range of items including Tea Pots from £2. 5 shillings, Dish covers from £1 5 shillings and Table Spoons from £2 8 shillings.

Then there's the eider down quilt offered by Heal and Sons "the most luxurious Covering for the Bed. The Couch or the Carriage".

The Patent Iris Fountain for "Perfumed and Other Waters" suitable for "Conservatories, Drawing Rooms, Dejeuners, Banquets, Public Dinners, Ball Rooms..." etc.

Heal and Sons offer "The Bed and Furniture of an Officer's Tent..."

There are numerous advertisements for clothes. Among the most frequent advertisers are Moses and Sons, Merchant Tailors who offers a wide selection of clothing including: "New Parisian Cape, While Waistcoats for Dress and Every Elegant Material and Style for Balls and Weddings, Dress coats, Liveries and Uniforms (including grooms and footmen) and Lounging and Morning Coats"

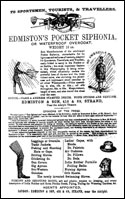

Edmiston and Son offer their "Versatio, or Reversible Coat..." that can used for a variety of occasions including "a gentlemanly morning coat...shooting or hunting coat...in any texture or colour required" and is Worthy the attention of the Nobleman, Merchant or Tradesman".

W. and J. Sangster advertise their "China Crape Parasols" and "richest Brocaded Silks ... and Alpaca Parasols, so much approved for the country and sea-side".

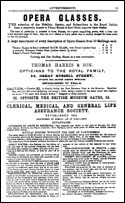

It is assumed readers of Bleak House would patronise the Italian opera. Thomas Harris and Son call for the "... attention of the Nobility, Gentry, and Subscribers to the Royal Italian Opera is respectfully directed to Thomas Harris and Son's newly improved Opera Glasses".

It is assumed that readers of this novel will have time to read much else besides the monthly parts of Bleak House.

Adam and Charles Black, publishers, offer a new Life of Lord Jeffrey, in two volumes.

Publishers William Blackwood and sons, offer several impressive titles including Samuel Warren's On the Intellectual and Moral Development of the Present Age; Sir Archibald Alison's History of Europe; Miss Agnes Strickland's Life of Mary Queen of Scots; Professor Johnstone's Elements of Agriculture and Thomas Doubleday's Mundane Moral Government; its Analogy with the System of Material Government.

Leading periodicals include The Field that is "devoted especially to Hunting, Shooting, Yachting, Racing, Coursing, Cricketing, Fishing, Archery, Farming and Poultry Keeping".

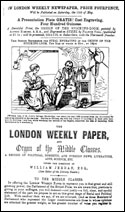

Readers of these monthly serial parts are inclined to take an interest in news and current affairs, as there are advertisements for the London Weekly Newspaper "and Organ of the Middle Classes" as well as Lloyds Weekly Newspaper, that shows elegantly dressed young ladies scanning the latest intelligence as they take a drive in their carriage that we note is manned by two liveried black servants.

Understandably, such middle class confidence stands on firm capital foundations. Banking services are advertised, such as those offered by the Bank of Deposit and Savings Bank: "...composed of two distinct and separate branches... one comprising the business of a bank of Deposit for the investment of Capital; the other, the ordinary transaction of Life Assurance..."

Bleak House Advertisements - Click on an image to enlarge

But, let us make no mistake; the claims made by BBC media publicity that our greatest novelist was churning out Victorian soap operas for mass popular consumption are quite unambiguous. Nigel Stafford Clark, who produced this new version of Bleak House, has no doubts on this score:

"We've set out to bring Dickens back to the audience for which he was writing...

He was unashamedly writing for a mainstream popular audience and that tends to get slightly forgotten today because his books have become classics.

His stuff was serialised and sold on the streets, so once a month a new episode of the new Dickens would come out and be sold like a magazine to everybody.

By the time he wrote Bleak House, Charles Dickens was very well established and there was enormous excitement and anticipation about each instalment.

People were excited in the way that they are now about a new series of a popular television drama like Spooks or Shameless.

If Charles Dickens were alive today, he would probably be writing big signature dramas like State of Play or Shameless. He would be writing for television because he recognised a popular medium when he saw it.

He was absolutely tuned in to the needs of an audience so he wrote for serialisation; he used cliff-hangers as a way of getting an audience to come back for the next episode".[33]

A lot might be learned by considering the actual purchase price of a monthly serial part of Bleak House at the time of its serialization. One shilling. The final double number was two shillings. John Sutherland rather straightforwardly says: "Dickens's novel was...first published as a monthly, illustrated serial in nineteen 32-page instalments (the last a 'double') between March 1852 and September 1853 and priced at one shilling (or 5p in today's money) a part". [34] But there's more to it than that. It is not really enough to say that a shilling in 1852 would be 5 pence in today's money. We need to know what 5 pence was actually worth in 1852. What would it buy? How much were people paid in 1852? Was 5 pence in fact worth very much or not in 1852?

There's no simple formula by which we accurately calculate the exact money values at the time of the publication of Bleak House. But we can surmise much when we take into account the money values of the early 1850s. [35] I do not think that a shilling was by any means a cheap publication. This was aimed at a middle class pocket. The advertisers wanted to reach a readership with a fair disposable income. During the serialization of Bleak House a housemaid earned £11 to £14 a year. A cook was paid between £11 and £17. A farm labourer was lucky to get about 7 or 8 shillings a week. Weavers during depressions received about 4 shillings and 6 pence, sometimes having to work almost seven days a week to earn it. (With compulsory church attendance taking up most of Sunday). In prosperous areas some trained and apprenticed working craftsmen got 40 shillings week. Domestic servants ranged from 50 shillings a year "all found". A butler might get £60 a year. A seat in the Canterbury Hall, a popular tavern and concert room, was 6 pence. Sam Weller was happy to get £12 a year and two suits. The well-to-do David Copperfield paid his pageboy £6.10 a year. Charles Dickens paid about 10 shillings (half a column) or £1 (a whole page) for contributions to Household Words and All the Year Round. Members of his editorial staff were paid £5 a week.

We have some interesting evidence of costs and money values in Bleak House. Guppy, Jobling and young Smallweed have their lunch at a dining house "of the class known among its frequenters by the denomination Slap-Bang" and feast on veal and ham, French beans, stuffing, three pints of half and half, marrow puddings, Cheshire cheese and three small rums. The cost is quickly calculated by Smallweed:

"Four veals and hams is three, and four potatoes is three and four, and one summer cabbage is three and six, and three marrows is four and six, and six breads is five, and three Cheshires is five and three, and four pints of half-and-half is six and three, and four small rums is eight and three, and three Pollys is eight and six. Eight and six is half a sovereign, Polly, and eighteen-pence out!"[36]

This lunch for three young legal gentleman cost nearly ten shillings, about 3 shillings 4 pence each. Guppy, an upwardly mobile, ambitious and aspiring young lawyer with a reputable firm, currently earns £2 a week. This slap-up lunch, then, would cost him nearly half a day's wages. A young lawyer in Guppy's position in the London today might earn about £25,000 a year. I'd calculate that with this information we may conclude that this lunch cost them nigh on £20 in today's money. (I recently cased this out in my part of provincial England, Bournemouth, where even an average pub meal with a pint of beer etc would cost well over £10 and a couple of spirits would add a few pounds to that). This gives us some idea of what the serial parts of Bleak House on sale at one shilling a month actually cost in the 1850s - between £4 and £5. Lavish glossy magazines in the UK today only cost about £3 to £4. It is obvious to me that such monthly serial publication was scarcely hawked about the streets to be sold to a mass public. It was aimed at a middle class public.

It All Depends on What You Mean by 'Soap Opera'

Whenever I hear such confidant assertions, my first inclination is to ask, what is meant by a "soap opera". And then to go on and ask, how much Dickens have you read? We can discuss the validity of the term "soap opera" is respect of Dickens's fiction in the light of modern media theory. The question of familiarity with Dickens's novels is a personal question. But the issue of attracting young contemporary television audiences to Dickens's fiction by presenting Bleak House in thirty minutes episodes twice a week following BBC-1's transmissions of EastEnders - in my view -- raises very fundamental cultural issues indeed. Then there are some important economic, political and commercial matters to take into account. But they cannot be avoided.

Let's see what light can be shed on the 'soap opera' claim by using contemporary media genre theory. The real cause of the trouble is the confusion of any form of serial fiction with a fairly specific genre, soap opera. Did Dickens write soap operas? Although everybody grabs at the name of Dickens when the question of serial publication crops up, it is important to stress that serial publication was standard practice in British publishing throughout the period.

As well as Dickens's fiction, novels by Thackeray, Maryat, Bulwer Lytton, Ainsworth, Charles Kingsley, Mrs Gaskell, Wilkie Collins, Charles Reade George Meredith Trollope and George Eliot (including Middlemarch).

Towards the end of the 1850s the publication of novels in monthly serial parts declined, as much of it was gradually taken over by the new illustrated periodical journals and illustrated magazines, made possible by advances in printing technology and improvements in graphics. This brought some of the period's greatest writers cheaply into British homes, in episodes accompanied with fine illustrations. (Among those to benefit from such publication was Thomas Hardy). As a genre, it seems to have originated in US commercial radio serials in the 1930s to sell soap powder mainly to housewives; hence its interests centred on families, friends, neighbourhoods.

Soap operas originated in 1930s American radio serials that were chiefly sponsored by leading soap powder companies. To reach their target audience these serial dramas needed regularly to attract housewives at home with serial dramas. These dramas combined features of literary romance and melodrama, had strong affinities with female orientation, easy to grasp moral issues and extreme emotions. Such long running serials were constructed with interlocking episodic narrative lines, full of surprising coincidences, unexpected twists and turns and plenty of cliff-hangers. Soap opera made a seamless transformation onto television. On the small screen soaps are long running, potentially endless serials, usually based on a road or a small community in which format/location is unchanging.[37] As the sensation is of an endless band of narrative, viewers can join at any time: "The longer they run the more impossible it seems to imagine them ending". [38] They seldom refer to events outside in the world outside, except royal visits etc.

British soaps are special in their working class location, probably the long term result of their emergence in the early days of ITV in the 1960s, a decade marked by the strong revival of British social realism - films and novels such as Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Room at the Top, Billy Liar, A Kind of Loving, plays by Arnold Wesker and John Arden and the popularity of such groups as the Beatles. The material is substantially repetitive including courtship, marriages, infidelity, divorces, deaths, disappearance, sudden arrival of "lost" friends or relatives. No single character is indispensable. Relationships are more important than plot. They continue to be aimed at women, especially working class women. [39]

Soaps have no beginning and no end, no structural closure. No single narrative thread dominates. The plot lines interweave different characters and situations all the time. Several stories may be carried on and over for a number of episodes.[40]. It has been argued that soaps with their structural openness represent a particularly feminine narrative form.[41]

All told, not much seems actually to happen because frequent action is rare. British soaps seem to supply a regular source of interest and anecdote that replaces gossip of former communities and generations.

To sum up. So far, so interesting. But media publicity is claiming that Dickens's fiction was the "soap opera" and that if Dickens were alive today, he'd be writing for Coronation Street, EastEnders etc. etc.

In my view this glib media blatherchat is culturally and historically illiterate. This soap opera claim will not bear examination and falls apart the moment one starts seriously to discuss the evidence. The main points that need exploration are genre/format, audience, narrative, authorial style.

Soap opera was a new genre pioneered on commercial radio in the USA. The aim was to attract advertising for soap, washing powders and domestic commodities by broadcasting an endless serial drama in short, daily episodes, aimed (mainly) at women listeners. The soap opera prototype thus created was centred on a locality (a street, locality) and dealt with the everyday goings-on of families, friends and neighbours. Storylines inevitably focused on relationships, love, loss, marriage and minor "tragedies". As the narrative thread was required to be unending, with no extreme actions or noticeable resolution, various interlocking and interchangeable themes recur. We all know what these are as we see them every week.

It seems clear to me that Dickens's novels do not conform to the established conventions of soap opera. Dickens's plots are never like this. The well-known fact that his novels were first published in serial form is a critical and theoretical red herring. Dickens's novels invariably have a recognisable beginning (exposition), followed by development, various crises and final resolution. They always have that sense of going somewhere towards a denouement in which all the threads are gathered up. Even apparently unconnected characters, themes, communities etc are always finally seen to be all inter related. The gender interests and social range is much wider than in soaps. Unlike soap operas, his locations are varied and often widely distant from each other. His appeal was mainly to the genteel lower or middling middle classes. They were aimed at a mixed readership.

Over and above these considerations, it can be said that Dickens's authorial style is certainly not that of soap opera. Soaps are not "realistic" yet they aim to achieve a surface quality of British social realism, strongly marked by the working class "realism" of the 1960s. Yet soap operas, because of their need for mass appeal, are ready enough to be Politically Correct, shy away from socially or politically controversial themes. [42]

The issue of social realism is interesting. Most modern critical and theoretical work on Dickens suggests that Dickens, unlike so many of his Victorian contemporaries, was by no means a social realist. It is a serious mistake to apprehend Dickens's achievement by approaching his fiction as social realism. He is not sensibly to be compared with, say, Emil Zola and his imitators [43]. His fictions are dreamlike, psychological, grotesque, fairytale versions of social experience. Yet he deals with real social issues, such as the conditions of the poor, work houses, education, prostitution, the class system and so on. As Harold Bloom commented: "...Although Dostoevsky and Kafka frequently shadow him, Dickens has no true heir in his own language. How can you achieve again an art in which fairy tales are told as though they were sagas of social realism?..."

Nor can I accept that if Dickens were alive today he would be writing popular television dramas. Yes, we know he loved acting and performing his own works. He enjoyed going to the theatre. There are frequent moments in his fiction that employ melodramatic effects. But we know from his own feeble attempts in writing for the stage that his gift for writing drama was feeble. His fascination with the theatre prompted him early in his life to try his hand at plays. None of his juvenile efforts survive. In 1836 The Strange Gentleman' (a version of 'The Great Winglebury Duel' in Sketches by Boz) was staged as an afterpiece at the St James's Theatre. It ran for a season. In the same year he wrote The Village Coquettes, a pastoral operetta (with music by John Hullah). This production was closed after a mere sixteen performances. He tried his hand at two more farces - Is She His Wife? and The Lamplighter. The former ran a couple of nights at St James's Theatre in 1837 and the latter went briefly into rehearsal at Covent Garden but was not staged. Apart from adapting a comedy of Mark Lemon's for his own use and helping Wilkie Collins on The Frozen Deep in 1857, this is all the evidence we have of the novelist's attempts in writing for the stage. The evidence is enough for us to conclude that he had little talent as a dramatist. I believe that Dickens's art is essentially literary, in the written word. It is here we see his genius. He was a master of expository prose; his essays and journalism are admirable. His letters encompass a wide range of passion, wit, sentiment and fascinating observation. His narrative fiction places him among the immortals. Paul Schlicke, writing of Dickens as playwright, puts his finger on it:

"None of these plays holds much intrinsic interest. It is a paradox that the most theatrical of novelists could not write a good play, but it seems apparent that he needed the greater canvass of the printed page and above all the controlling authority of a narrative voice, to breathe life into stock melodramatic plots and type figures|".[44] "

However successfully BBC-1 might be in transforming Bleak House into a TV soap opera, to claim that Dickens wrote soap operas either shows an understanding simple and unschooled, or a willingness deploy deception and half truths in publicity and marketing.

There is another important point to be raised. As Professor John Sutherland points out, Bleak House had serious satirical intentions. Dickens wanted to draw attention to the shortcomings of the ways the British legal professions worked as a self-serving system. Soap operas do not have such serious social imperatives:

"Victorians, rightly, saw Dickens not merely as a great entertainer, but as force for progress. He wrote, as the Victorians put it, 'fiction with a purpose'...Hence the j'accuse in such moments as that when Jo finally succumbs to the 'deadly stains' among which he passed his short, wretched life...You want to know how to make a better world? Asks Dickens. Start in front of your nose. It is as appropriate a message now as it was in 1853, but you won't find that message in EastEnders. At this point, the soap opera and the Victorian novel part company".[45]

Drumming Up the Ratings: Getting Young Recruits

We now come to the question of the usefulness or effectiveness of attracting younger television viewers by transmitting this "soap" version of Dickens novel seamlessly infiltrated into the schedules so as to follow populist audience-puller EastEnders.[46]

Posing such a question inevitably leads us into deep cultural matters. It seems to me that today's young audiences/consumers are conditioned by market imperatives always to crave for the new. Music, clothes, entertainment, recreations - armed with the latest in marketing, advertising, technology, mass production - constantly create appetites for the very latest that can be consumed.

You may observe how the processes of social/cultural conditioning produce generations of adolescent consumers. Very young children who are new to the world and its multifarious variety take life as they find. They take their experiences and gradually process them in order to make sense of the reality they find themselves in. Clothes, age, colour, race are indifferent to children. Their curiosity makes them eager to understand what they find, and process and collate new experiences. To children the whole world is a strange place and therefore, paradoxically, nothing is strange. Gradually they begin to make some sort of sense of their environment and develop a sense of congruity. A growing child shows its maturity by recognising that its mother has a new hat or, if it is served something unusual to eat. A child watches television, for example, and reads all that it sees on face value.

But gradually you may observe they piece together a cultural awareness. They begin to search for things to which (to use the appropriate term) they can "relate to". They begin to look for the things they know, their own kind, personalities, music, clothes and all the rest of it, out of which "their world" is constructed. An old film, showing people in old-fashioned clothes, or driving out of date automobiles, makes then laugh. These things now strike them as incongruous -- in terms of the world they now assume they belong in. They live in a continuous present.

It now takes quite a sophisticated cultural step to rise above the limited here-and-now and see the timeless themes of drama, literature and the arts.

Just to consider literature and drama, for example. It is this highly sophisticated -- but restricting cultural conditioning -- that makes reading the classics so difficult. It takes considerable effort to get beyond the 1940s costume and toff accents of Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson and realize the terrible tragedy that overwhelms the lovers in David Lean's masterpiece Brief Encounter. Or to apprehend the weight of social convention that almost stifles the possibilities of human fulfilment in Jane Austen's fiction. Yet the tensions between what we as human beings want to do, and what the social conventions (that as human beings we have all played a part in creating) will allow us to do, continue one of the enduring themes of literature.

In my more pessimistic moments I feel that beneath regular announcements of triumphant school examination results and more graduates, the nation's culture endures the effects of long-term malnutrition. And despite these impressive statistics, there's a common feeling in Britain that education is not altogether what it was. Employers regularly complain, both in terms of comments made during media interviews and in official publications, that school leavers today do not have the required level of English and mathematical achievement. [47]

Several recent books lamented the state of our culture -- John Humphrys' Devil's Advocate, George Walden's The New Elites, John Drummond's Tainted by Experience, and John Tusa's Art Matters. We seem to have shut ourselves off from what has gone before -- Arnold's best that has been thought and written. We don't need any of this old luggage now. But does transforming a classic into what is perceived to be an "accessible" form really offer a route by which younger, modern audiences may rediscover the classics? How many people discovered the glories of Verdi as a result of Jonathan Miller's Godfather version of Rigoletto? Did Baz Lurman's contemporary New York gunslinger Romeo and Juliet lead audiences back to Shakespeare? How many young readers enjoyed Chaucer as a result of BBC television's modern settings of a selection of Canterbury Tales? And this season the BBC promises to transmit new vamped versions of a few Shakespeare plays. All these attempts to render classical works "accessible" have in common the attempt to render works of art in terms of what an audience will find not find strange, to render them as somehow in familiar terms. This new BBC-1 version of Bleak House is another part of this characteristic effort in cultural production to render classical works "accessible" to younger audiences.

G. K. Chesterton believed that education was a process in which the soul of country was passed from one generation to the next. Somehow or other, this does not seem to be happening as in previous generations. But then, in modern cultural production and consumption, there are much wider influences at play.

A poll carried out by ICM this year indicated that among viewers aged between 14 and 21 who had access to Freeview (a free digital service backed by the BBC) only one in ten chose

BBC-1as their favourite channel. None chose BBC-2 or BBC-4. Or even BBC-3, that's aimed at younger audiences. One in four chose E4, designed by the Channel Four to appeal to this age group. One in four chose the music channel The Box. As newspaper report commented: "The results suggest that for the first time in its eighty three year history, the BBC risks losing the close relationship with viewers and listeners on which it relies to maintain the public support for the licence fee". [48]

It seems to me that in Postmodernism we are living through a period of profound cultural change. Basic assumptions about aesthetics and "classical" status are being overhauled. These signs, I suggest, are symptomatic of much wider revolutionary change. It all has economic deep structures, of course. The causes are all to do with trade, commerce and money making. In previous generations very largely the business of socially transferring the culture from one generation to another was done, as it were, vertically - from elder generations (parents, family, teachers) to the younger generations (children). Thus retain evidence in nursery rhymes, say, that goes back to the sixteenth century.[49] But now, in a world dominated by the free market and globalization, culture is a matter of commodification in which transaction between the generations is replaced by populist consumerism, in which the imperatives of fashion and constant novelty are supplied by mass production, marketing and publicity. That "high culture" survives at all is the result of state funding, education, sponsorship and, in the UK, public service broadcasting. (Well, up to now).

And the general symptoms are very not encouraging. Television programming in the UK today is wholly at the mercy of the imperative of the ratings. Consequently British television drama is now almost totally given over to medical and police series. Cinema audiences are on the increase, but the really successful films achieve success by means of violence, sex and stunning special effects.

The British Broadcasting Corporation still endures the long-term effects of Thatcherism. Throughout the 1970s, in a period of raging inflation, rising production costs and strong union pressures, when the BBC appealed for increased financial support from public funding, they were advised to borrow and service any loans in line with usual business practice. Thatcherism, on the other hand, required a more "sensible" and thrifty housewifely financial policy. Cut your coat according to your cloth. Make ends meet by cutting expenditure in line with income.

In effect, the BBC was encouraged to recognise that it had to be seen as deserving its licence fee. Consequently, for the first time in the Corporation's history, the BBC was competing in the ratings with commercial television.

If the BBC proved its worth as a provider of "public service broadcasting" by evidence of public satisfaction (i.e. numbers of viewers) then it would "deserve" its licence fee. Value for money must be pursued and be demonstrably achieved.

The BBC continues to feel pressure following the Andrew Gilligan affair and the ensuing Hutton Enquiry. All was to surface in the critical period during the run up to the renewal of the BBC Charter and Licence Fee. Recent media commentators have noticed, as competition with commercial television, satellite and cable stations has increased, the Corporation has shown signs of featuring more populist programming on BBC-1, a tendency for a more "Blue Peterish" quality[50] in arts and humanity programming on BBC-2, and side-lining its high fallutin' music, drama and documentary programming to

BBC-4.

As I was researching and writing this, the BBC was currently experiencing industrial action from broadcasting unions following the announcement by Mark Thompson that 4,000 BBC staff job losses (1 in 10 in staff in making news, sport, and drama programming) would result in "saving" £533,00,000 and these savings were in turn to be invested in "quality" programming -- sport, news and drama. Therefore, this new populist TV version of a great classic may presage a whole new stage in the BBC's long tradition in the production of classic serials. From the previews I have seen I believe it will do nothing but good. Whether it will bring younger viewers flocking back to classical literature will for the moment be a matter of speculation, but Andrew Davies's television version of Bleak House, whether "soap opera" or not, is as good as it gets.

It has long been my opinion that British TV versions of Dickens err on the side of worthy, social realism. They miss the real essence of Dickens's fiction. He used his creative imagination to portray the real world, that we are conditioned to see as a rational and reasonable place, as it really is - a grotesque parody of reality. He puts before us a dream-like melodrama, a mixture of the phantasmagorical and sentimental, the grotesque and the comic - all at once. It is not "realism". It is a unique hyperrealism, as convincing, comic and frightening as our dreams. The disturbing thing is that as often as not we find the apparently implausible, exaggerated and distorted visions in Dickens's world are securely based on realities - realities we had not truly perceived before.

The traditional British academic/critical approach to evaluate Dickens's literary achievement has been in terms of his realization of "Victorian England". British critical endeavours have sought to justify an admiration for Dickens's fiction in direct ratio to its basis in some recognisably historically accurate 19th century social veracity. This characteristic British school is well exemplified by such influential publications as John Butt and Kathleen Tillotson's Dickens at Work 1957 and Humphrey House's The Dickens World 1942. And yet there's a characteristic paradox right to the heart of Dickens's artistry. Often his seemingly wildest effects are firmly based on solid historical evidence. The incredible case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, that ties all persons and themes of Bleak House together, is actually based on the infamous case of an old miser, William Jennings 1701-1798.[51]

Of the BBC's attempts in recent years with Dickens, Hard Times was a didactic bore; Great Expectations omitted all the comedy and Little Dorrit was rather heavy and operatic. But here in Bleak House we have the best attempt at something truly "Dickensian" that I have ever seen on the small screen. It is true to the spirit of the original.

Bleak House was written as the nation confidently celebrated its faith in Progress in the Great Exhibition 1851. This is an elaborately plotted, vast canvas and although clearly a satire on the law's delay, it combines several important Dickensian themes. These are presented metaphorically in the pervasive images of fog, damp, mould and rain, and in the central terrifying image of contagious disease. Dickens presents modern society and its major institutions (politics, the law) as a vast, confused, stifling muddle, in which the various antagonistic layers of the severely separated social classes are nevertheless interconnected in ways they do not suspect. The action moves from the Deadlock's stately country home, through law courts, lawyer's offices and provincial life, to the darkest recesses of the slums. The mainspring of the plot is the endless suit in the Court of Chancery, to which parties from all layers of society, from the very highest to the most humble, are ineluctably drawn as to a vortex. Smallpox kills the pathetic crossing-sweeper, Jo, but it also infects Esther, who is the secret love child of Lady Honoria Dedlock. The Corporation's declared aim was to pull in younger viewers. It is interesting to note that in the UK the first hour long episode was scheduled to follow a special nightly series of episodes of BBC-1's popular medical soap operas Casualty and Holby City and EastEnders. Thereafter the remaining 30-minute episodes are transmitted twice a week to follow episodes of EastEnders.

It's interesting to note that Charles Dickens himself did very well out of Bleak House. He made £11,000. This made him, in the words of a contemporary "a literary Croesus".[52] In today's money that would be approximately £770,000[53]. At a shilling a month Bleak House sold an average monthly figure of 34,000 copies. The population of the UK at the time was about 28,000,000. A " Best Seller" today is usually 10,000 in hardback. Thus about 14% of the population of Dickens's day bought the monthly parts of Bleak House. We'd need to multiply that by about 6 to get the readership. A comparison with the ratings achieved by the BBC's proclaimed soap opera version of Bleak House will be interesting.

This new Bleak House will not entirely obliterate memories of Arthur Hopcraft's 1985 version for BBC-2, but it's vintage Davies, worthy to rate with his Middlemarch, Pride and Prejudice and The Way We Live Now. He has done what he does best - fillet a novelist's complex narrative and relay it more or less completely in television terms. It cost £8 and it shows. Production values are very high. Art work superb. A tremendous cast deliver the goods and the moments of high drama are well worked up. I loved the touch of the weird and the grotesque. Dickens does not translate naturally to film/TV. Whether it's the result of scheduling the series to follow EastEnders, or the star cast or simply the high quality of Andrew Davies's dramatizations and its production, Bleak House has secured good ratings. Although not as impressive as Andrew Davies's sensationally successful Pride and Prejudice in 1995 (average weekly figure of 10 million) the ratings for his new Bleak House have been good. The initial hour long episode gained 6.6 million and the following twice-weekly 30-minute episodes earned an average 5.9 million viewers. We can compare this favourably with some landmark ratings figure of recent British television -- an estimated 21.1 million watched the BBC's Panorama interview with Princess Diana on 20 November 1995. This was an estimated 83% share of the total television audience. This may be compared with the 7.7 million who watched Jonathan Dimbleby's interview with Prince Charles on commercial television and the 27 million in 1987 who watched the episode of Coronation Street in which Alan Bradley attempted to murder Rita Fairclough).[54] Davies has not done a full length Dickens before but seeing this Bleak House makes me long to see what he'd do with Pickwick Papers, Barnaby Rudge, Dombey and Son or A Tale of Two Cities. I do not know whether Bleak House will attract younger viewers, but I'm sure it will encourage more people to savour the unique art of our greatest novelist.

Robert Giddings, Professor Emeritus, School of Media Arts and Communication, Bournemouth University.

[1] See Graham Petrie: 'Silent Film Adaptations of Dickens Part 1: From the Beginning to 1911' in The Dickensian 97: 215-41

[2] And this despite the strongly argued case for its cinematic qualities from Eisenstein on - see Graham Smith: Dickens and the Dream of Cinema 2003 pp. 9, 14, 34, 73-76, 82, 98, 100, 109-110, 148, 153-4, 156-64 and 174. There were several short early silent films about Jo the Crossing Sweeper and a couple of attempts to film the main storylines in the early 1920s. It has not regularly been done on television. BBC Television broadcast a serial television version by Constance Cox in 1959. BBC-2 broadcast a greatly admired dramatisation by Arthur Hopcraft in 1985 with a star cast. See John Glavin (ed): Dickens on Screen 2003 p. 210.

[3] Interview with the author, December 2004

[4] Interview with the author op. cit.

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] Guardian Unlimited 20 April 2005.

[9] Is there, in fact, a writer with a bigger name than Shakespeare? I only asked. The heroine of BBC-1's promised The Taming of the Shrew is "ruthlessly ambitious MP 'Much Ado About Nothing' is transported to an ego-fuelled regional news programme, with Billie Piper playing Hero...and Macbeth' is transported to the pressure cooker atmosphere of a top London restaurant kitchen. 'A Midsummer Night's Dream becomes a romantic comedy set in a caravan park starring Imelda Staunton and Johnny Vegas as Bottom".

[10] The Stage: 18 January 2005

[11] Nathaniel Parker's Fansite 19 May 2005.

[12] I find it odd that such a respected British political journalist should take it upon himself so fulsomely to opine on such complex literary matters. Preston has a considerable and well-earned reputation for investigative political journalism. His reputation is mainly based on his investigative reporting while editing the Guardian, into British Conservative Party Members of Parliament, notably Jonathan Aitken and Neil Hamilton. These were so-called "sleaze revelations", cash for questions and corruption in parliament that certainly played a part in discrediting the Major government and contributed to its defeat by New Labour in 1997. Such reporting is based on scrupulous examination and dogged dependence on evidence. Yet here he is with little established reputation in literary matters and with scant regard for anything resembling evidence, arguing a very tendentious case.

[13] Peter Preston: 'The Literary World is Happy, But Wrong to Judge Books by the Categories They Fit Into', the Guardian 17 October 2005 p. 28

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid

[16]Coronation Street has been running on Granada Television since 1960 and "unlike other soaps has appealed to a wide range of fans, one of the most passionate in his support was the poet laureate, John Betjeman...." Bamber Gascoigne: Encyclopaedia of Britain 1994 p.158. Betjeman's affection is just one manifestation of his cultivated "English" eccentric foolery that included Archibald Ormsby-Gore, his well-worn teddy bear. Invited to dine at the Savoy with his future mother-in-law, Lady Chetwode, he arrived wearing an elasticated bow tie that he plucked and twanged at table. When asked how he earned his living, he replied, "I'm in lino". Humphrey Carpenter: The Brideshead Generation: Evelyn Waugh and his Generation 1989 p. 262.

[17] Francis Wheen: Hoo-Hahs and Passing Frenzies, Atlantic Books 2002 p.263

[18] Andrew Davies, interview with the author, December 2004

[19] Ibid

[20] Ibid

[21] Ibid

[22] Ibid

[23] Ibid

[24] See John Feather: A History of British Publishing 2000 p. 113. The novel was Sir Lancelot Greaves, published in serial form in The British Magazine in twenty-five parts between January 1760 and December 1761.

[25] Novels were published in serial parts in newspapers. A feuilleton was a supplement attached to the political portion of a French newspaper that might contain social gossip, art criticism, fashion, theatre news and cultural comment, invaluable in maintaining the vitality of boulevardierisme (the comparison with modern coloured supplements is all too obvious). Such supplements of light journalism and social/cultural comment were pioneered by the Louis Francois Bertin (1766-1841), the celebrated journalist and founder of the journal des debats, to whom is attributed the development of serial fiction. Serialised novels began to appear in the early 1830s by such writers as Eugene Sue, Frederic Souli, Balzac, Dumas pere and George Sand. The term feiulleton was in use in England in the 1840s.

[26] This must be born in mind when considering the sales of serialised novels. The readership would be greater than the sales of individual numbers. This, too, was a characteristic of the readership of novels serialised in fieulletons. There are engravings of groups of office and industrial workers listening to such novels as they are read aloud by colleagues.

[27] John Sutherland: Victorian Fiction: Writers, Publishers, Readers 1995 pp. 86 pp.; N. N. Feltes: Modes of Production of Victorian Novels Chicago 1986 pp. 1 ff. and Robert Giddings: The Author, the Book and the Reader 1991 pp. 95-104.

[28] See Louis James: Fiction for the Working Man 1974 pp. 2-13.

[29] See Raymond Williams: Problems in Materialism and Culture 1998 pp. 170-95 and Bernard Darwin: The Dickens Advertiser 1930 pp. 26 ff.

[30] Graham Smith: Dickens: A Literary Life 1996 p. 27. See also John Sutherland: Victorian Novelists and Publishers 1976 p 21 ff and Victorian Fiction: Writers, Publishers, Readers 1995 pp. 88-91.

[31] Dickens: Preface to the first cheap edition of Pickwick Papers, reprinted in The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, edited by Robert L. Patten 1972 p. 45.

[32] Bernard Darwin: The Dickens Advertiser 1930 pp. 144-155; 195; 197 and 202-7.

[33] BBC Television Drama press release, October 2005

[34] John Sutherland: Inside Bleak House 2005 p. 9

[35] For the information that follows I am indebt to several sources, especially Patrick Howarth: The Year is 1851 1951; Peter Wilsher: The Pound in Your Pocket 1971; James Buchan: Frozen Desire: The Meaning of Money 1997 and Christopher Hibbert: The English: A Social History 1066-1945 1987.

[36] Bleak House, Chapter XX

[37] Usually filmed on permanent sets, initially a considerable production cost, but ultimately an economic way of doing things. The set of Granada's Coronation Street is now a tourist attraction that numbers Queen Elizabeth II among its visitors. See Richard Dyer (ed): Coronation Street, BFI 1981

[38] Christine Gerachty: Women and Soap Opera: A Study of Prime Time Soaps Cambridge 1991 p. 11.

[39] Mainly women and those in lower socio-economic groups Sonia Livingstone Livingstone Making Sense of Television, Oxford 1990 p.55

[40] David Buckingham: Public Secrets: EastEnders and its Audience, BFI 1987 p. 36

[41] Tasnia Modleski Loving With a vengeance: Mass Produced Fantasies for Women Hamden, Connecticut, 1982.

[42] Direct political issues are totally avoided, but a good selection of Politically Correct themes are regularly presented in British soaps. The signs are quite interesting. Characters and storylines incorporating ethnic families, troubled teenagers, unmarried mothers, and drug problems have been featured.

37 Marx taught that man made his own history, and that could intervene in history, and further, it was not the consciousness of men which determines their being, but on the contrary, their social being which determines their consciousness. Auguste Comte, the founder of positivism, believed that a superior state of civilization could be achieved by means of the science of sociology, by means of which persistent social problems would eventually be solved. Some theorists believed that Darwin's ideas had not only discredited belief in God, but that the principles of Darwinism could be applied to human society -- consequently Social Darwinism inevitably led to the theory of the Superman (as developed by Nietzsche and portrayed by Shaw). Hippolyte Taine put forward new theories of literature based on some of these scientific principles (Histoire de la litterature anglaise 1864, La Philosophie de l'art 1869, ) and gave birth to Naturalism in fiction. Taine's literary philosophy was that it was the duty of creative literature to portray human society as objectively as scientists observed nature. Naturalism absorbed the biological theories of Darwin and the economic determinism of Marx. Romantic subjectivism was firmly shown the door. Stendhal, Balzac and Flaubert were in some way precursors of the movement, but in Daudet, Maupassant and above all in Zola the doctrines found their most powerful expression. Emil Zola was particularly responsive to Taine's ideas and concentrated on a meticulous accuracy of detail, immense detail and detached observation.

[44] Paul Schlicke: The Oxford Companion to Dickens, 1999 p. 455

[45] John Sutherland: Inside Bleak House 2005 pp. 23-4.

[46] This statement should really be somewhat qualified. Currently EastEnders gets around 6 million viewers. And it is worth noting that Andrew Davis's dramatization of Pride and Prejudice got an average of 10 million viewers in 1995. Even BBC-2's version of Peake's Gormenghast (that was so savagely attacked as a waste of the Corporation's money by The Times) regularly earned a viewing figure of around 4 million.

[47] Sir David Normington, permanent secretary at the Department of Education and Skills, was reported in the press on 13 October 2005 as reporting to the Commons Education Select Committee that as an employer himself, he sympathised with employers and university tutors "who complained of poor standards of English and maths among young people...I sometimes see that the standards of English and maths are not good enough among those coming into my employment". Sir Digby Jones, Director-General of the Confederation of British Industry said that too many young people left school "unprepared for work". One third of employers were forced therefore to give new staff extra classes in English and maths". 'Many School Leavers Lack Basic Skills Admits Education Head' in the Guardian 13 October 2005.4.

[48] Owen Gibson: 'BBC Risks Losing Touch With Younger Generation of Viewers', the Guardian 7 October 2005.

[49] The erosion of cultural continuity, it seems to me, begins somewhere in the 1960s. According to researchers such as Iona and Peter Opie, working in the 1950s, one in nine of the traditional, standard nursery rhymes were known when Charles I was executed. Forty per cent were recorded before the close 18th century. About one in four would have been known when Shakespeare was growing up. But this vast natural spring which refreshed generation after generation seems now to be drying up. See Iona and Peter Opie: The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren 1959 pp.1-16 and The Oxford Book of Nursery Rhymes 1958 pp. 7 ff.

[50] Blue Peter was a long running BBC television children's magazine programme founded in 1958. Solidly middle class and "worthy", it mixed entertainment with right thinking, sensible social awareness.

[51] He was the son of Robert Jennings, an aide-de-camp to the Duke of Marlborough. For a time he was page to George I but after 1722 he retired to his country house in Suffolk and devoted his life to accumulating money. He achieved a massive fortune by lending at exorbitant rates and excessive thrift - he never married, was shabbily dressed and ate and drank little. He frequented the gambling houses of London where lent money at high interest and accumulated a fortune over £2,000,000. He was said to be the richest commoner in the country. He died intestate at Acton, in Suffolk, in 1798 at the age of 97. A will was found, sealed but not signed. This was explained, on the evidence of a household servant, by the fact that Jennings had inadvertently left his spectacles at home when he went to complete these arrangements with his solicitors. He subsequently simply forgot to sign and witness the document. The estate was in dispute because survival relatives now claimed that William Jennings was not the son of Robert Jennings. Other members of the family claimed more direct descent. Earl Howe and rival claimants attempted to have subsequently claimed the estate these claims set aside. The case dragged on in the Court of Chancery involving seventeen cases brought before the Court. Costs of at least £100,000 were accrued in making enquiries, searches and copies of legal documents. When one of the claimants died in 1915 it was still unresolved. Costs had amounted then to £250,000. See Edgar Johnson: Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph 1952 pp. 763-4 and

770-1 and William S. Holdsworth: Charles Dickens as Legal Historian 1928 pp. 79-115. See also http://fred.love.home.mchsi.com/jennings/williamcj/jenndoc.html

[52] Robert Patten: Dickens and his Publishers 1978 p. 233.

[54] Jon E. Lewis and Penny Stempel: The Ultimate TV Guide, Orion 1999 p 80.