Special Guests > Moskovitz: Boz and the Bard

Boz and the Bard

By Herb Moskovitz

Presented to The Philadelphia Branch of the Dickens Fellowship, November 22, 2014 and The Friends of Dickens New York, February 7, 2015

Reprinted with the kind permission of the author

Published on this site February 25, 2015

GADS HILL

Location, Location, Location of the action in his stories was very important to Charles Dickens. He constantly used real locations in England, many of which one can still visit: The Nancy steps on London Bridge, the George and Vulture, Satis House, and the Pump Room in Bath, all come to mind.

Dickens was as fascinated with Shakespeare as much as we are with Dickens, and much like we visit the Dickens Birthplace in Portsmouth, he visited the Shakespeare Birthplace in Stratford. But we don't just visit real places that are placed into the stories. We visit places where fictional events supposedly took place. Events that never really happened. We visit the graveyard in Cooling where Magwitch accosted Pip and Dickens visited the house of the Capulets in Verona. In fact, when one looks at a list of the towns Dickens visited in Italy, one realizes that he was visiting the towns where Shakespeare's plays took place.

But there is one place on earth that has as much importance to Dickensians as to lovers of Shakespeare: Gads Hill. How did this one small hill become so important in the lives of the two great authors?

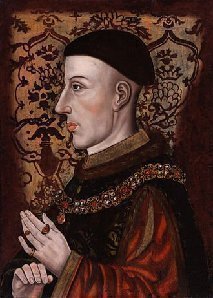

In the late sixteenth century, there was a popular story about the great English king, Henry V,. Historian John Stow wrote that in the early fifteenth century, Prince Hal when he was a youth, "would wait in disguised array for his own receivers, and distress them of their money: and sometimes at such enterprises both he and his company were surely beaten: and when his receivers made to him their complaints, how they were robbed in their coming unto him, he would give them discharge of so much money as they had lost, and besides that, they should not depart from him without great rewards for their trouble and vexation."

About the same time that John Stow wrote that, Edward de Vere, the future 17th Earl of Oxford, age twenty-three, played a similar prank. Young de Vere was very much like what Prince Hal had been – unpredictable and unreliable. On May 20th, 1573, two men on official business for William Cecil, Lord Treasurer Burghley, were carrying money for the Exchequer. At the top of Gads Hill in Higham, and this is the first time that Gads Hill comes into the story, de Vere and two of his men jumped out from hiding places and robbed the travelers. I presume they returned the money to the victims with "great rewards" like Hal had done. This prank was talked about throughout the realm.

At this time, The Queen's Men was the leading theatrical company. They came before The Lord Chamberlain's Men – which was Shakespeare's company, and around 1583, they performed The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth. The author's name is lost to us but it was a "raucously comical play," and a forerunner of Shakespeare's plays.

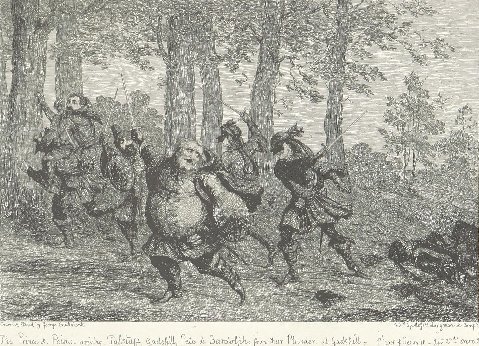

In it is the same prank which takes place in the same location as de Vere's escapade: Gads Hill. There is no doubt that Shakespeare then took the same location for his retelling of the tale in Henry IV, part I.

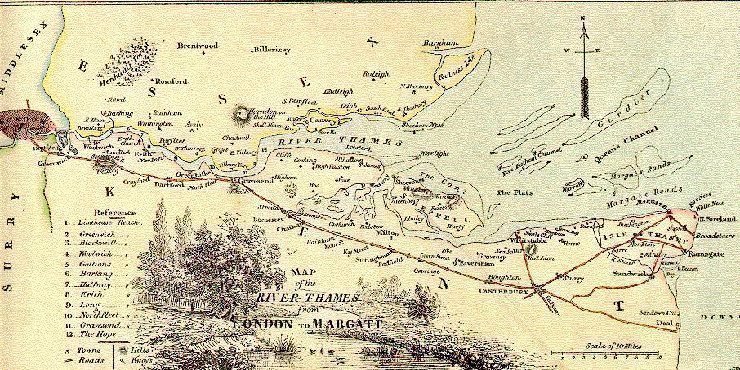

Gads Hill is located in Higham, on the Dover Road that leads from Gravesend to Rochester. It is one of the oldest roads in England, going back at least to Roman times.

When Dickens was a boy, living in Chatham, his father would take him for long walks in the countryside.

They would often take the Dover Road and pass a Queen Anne style house at the top of Gads Hill. Dickens later wrote...

"I used to look at it as a wonderful Mansion (which God knows it is not) when I was a very odd little child with the first faint shadows of all my books in my head - I suppose."

Dickens tells us in chapter VII of The Uncommercial Traveller that he knew all about Falstaff by age 9. "This is Gads-hill we are coming to, where Falstaff went out to rob those travellers, and ran away."

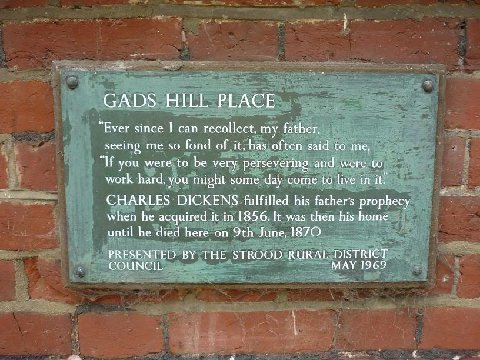

"And ever since I can recollect, my father, seeing me so fond of it, has often said to me, 'If you were to be very persevering, and were to work hard, you might some day come to live in it.' "

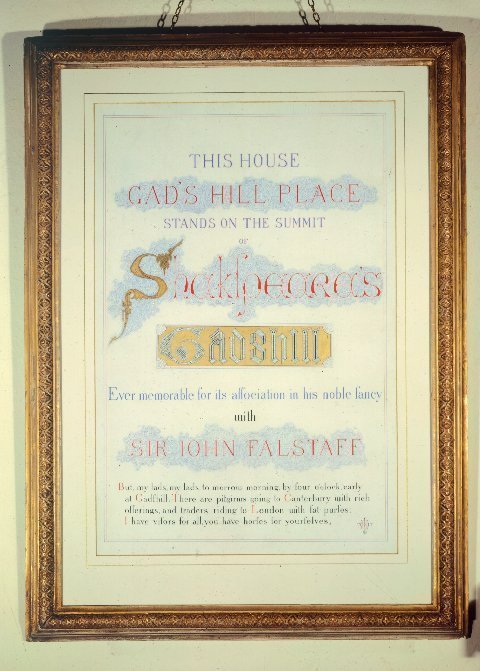

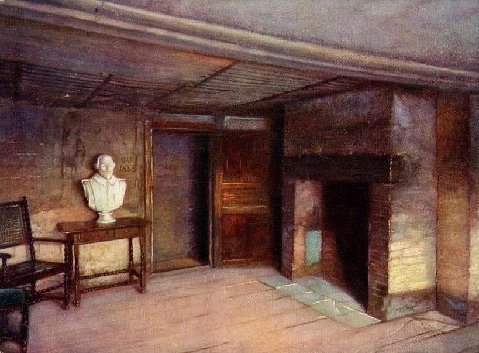

In 1856 the house was put on the market and Dickens purchased it. He was very proud of the Falstaff connection and immediately had a framed illuminated scroll made up which he placed in the entry hall.

"THIS HOUSE, GADSHILL PLACE, stands on the summit of Shakespeare's Gadshill, Ever memorable for its association in his noble fancy with Sir John Falstaff. But, my lads, to-morrow morning by four o'clock, early at Gadshill! There are pilgrims going to Canterbury with rich offerings, and traders riding to London with fat purses."

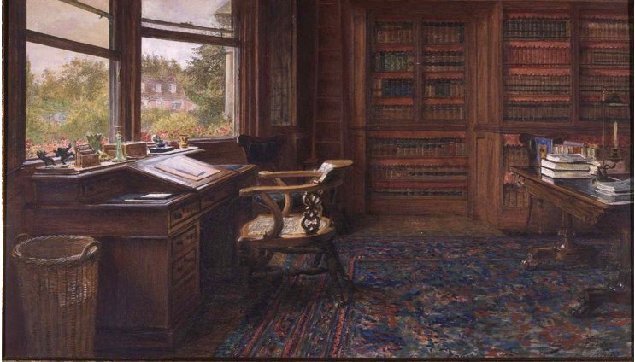

Dickens set up his study on the ground-floor to the right of the front entrance. In a letter to a friend Dickens claimed, "The robbery was committed before the door, on the man with the treasure, and Falstaff ran away from the identical spot of ground now covered by the room in which I write.

A little rustic alehouse, called the Sir John Falstaff, is over the way – has been over the way, ever since, in honour of the event."

This amazes me. Dickens has now taken an event that never happened three hundred years before, and firmly believes he knows exactly where each action of the non-event took place.

Dickens lived the last ten years of his life at Gads Hill Place, and he died there, The house still stands and is a mecca for Dickensians from around the world. Here we see visitors from Portsmouth, London, Germany, Delaware and Japan.

And across the street, just as Dickens described it, is the Sir John Falstaff tavern. It's been there for centuries.

CHILDHOOD

So we have just heard that Dickens was familiar with Sir John Falstaff by age 9. We don't know if he learned about Sir John from the original plays that his parents may have owned, or a child's story-book, like Lamb's Tales from Shakespear or his parents' storytelling.

We do know that he was going to the theatre at a young age. Before he was ten he went to the small Theatre Royal in Rochester where he saw Richard III and Macbeth. "The sweet, dingy, shabby little country theatre, we declared, and believed to be much larger than either Drury Lane or Covent Garden."

"Richard the Third, in a very uncomfortable cloak, had first appeared to me there, and had made my heart leap with terror by backing up against the stage-box in which I was posted, while struggling for life against the virtuous Richmond. It was within those walls that I had learnt as from a page of history, how that wicked King slept in war-time on a sofa much too short for him, and how fearfully his conscience troubled his boots."

When Dickens turned 18, he qualified to possess a reading card for the Library of the British Museum, and he immediately started on a reading program that was heavy on Shakespeare.

As a young man he went to the theatre "every night, with very few exceptions, for at least three years."

He wrote two plays, (both are lost) and a Shakespearean travesty O'Thello, or the Irish Moor of Venice. Only a few pages survive and they don't have much to do with Shakespeare.

As he grew up he developed his talents for acting and mimicry. At Wellington House Academy he entertained his fellow clerks, as one of them reported, with imitations of "the low population of the streets of London in all their varieties" and "the popular singers…whether comic or patriotic...He could give us Shakespeare by the ten minutes, and imitate all the leading actors of that time."

FRIENDS IN THEATRE

When he was still a young man, Dickens made many personal friends in the theatre. He was elected to the Garrick Club in January of 1836, while he was writing The Pickwick Papers. The Garrick Club had been formed in 1831 to "tend to the regeneration of the Drama." The leading actors, designers, managers and playwrights were involved. Soon leading authors, artists and nobility were joining. The club still exists.

In 1838 Dickens became a member of the Shakespeare Club which held weekly meetings where the approximately seventy members would present papers, do readings or just talk about the Bard. The club only lasted two years, but when it collapsed, a new club, The Shakespeare Society, formed. Every year Dickens and Forster would celebrate Shakespeare's birthday together.

MACREADY

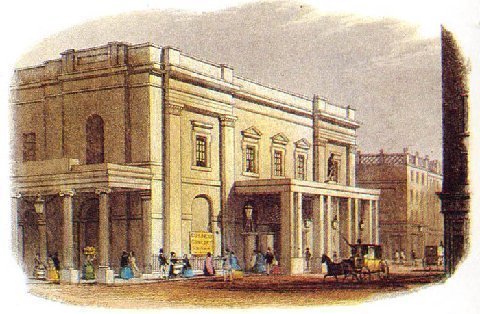

Forster introduced Dickens to William Charles Macready, the foremost Shakespearean actor-manager of the day, in June of 1836. When Dickens published Nicholas Nickleby in 1838, he dedicated the novel to Macready. Macready became one of Dickens's closest friends and Dickens became a trusted artistic adviser to Macready when Macready became the manager of

Covent Garden Theatre Royal in 1837 and 38, and attempted to restore Shakespeare to the original scripts after decades of drastic rewriting by the likes of Nahum Tate and Colley Cibber. Dickens attended rehearsals and made suggestions which Macready paid attention to. Macready and Dickens were very much interested in that the scenery and costumes were historically accurate.

Above we see Macready in his most famous role, Macbeth. Macready had developed a stance for Macbeth before Duncan's murder that became famous and copied by other actors. Dickens doesn't mention Macready by name, but his readers would have known who he was talking about when he writes about a waiter in The Mystery of Edwin Drood...

"And here let it be noticed...that the leg of this young man, in its application to the door, evinced the finest sense of touch: always preceding himself and tray (with something of an angling air about it), by some seconds: and always lingering after he and the tray had disappeared, like Macbeth's leg when accompanying him off the stage with reluctance to the assassination of Duncan."

Here we see Macready as Shylock

Hamlet

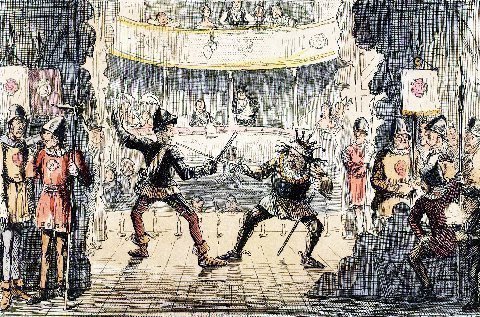

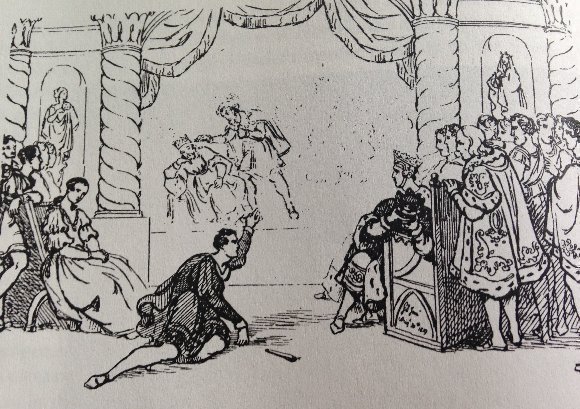

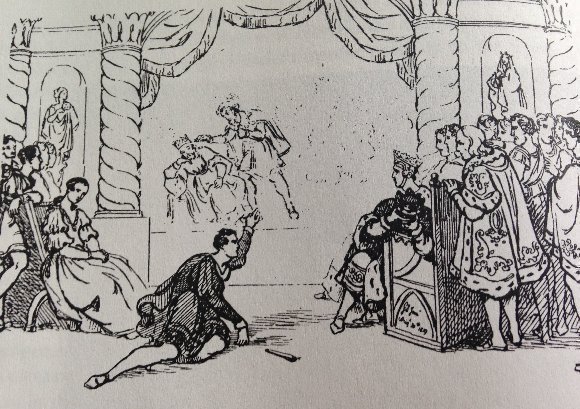

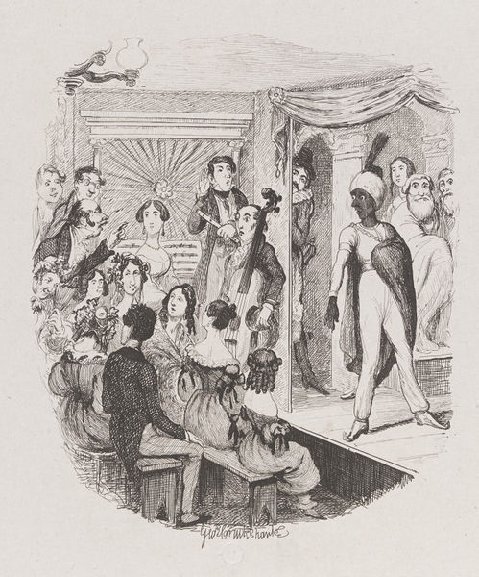

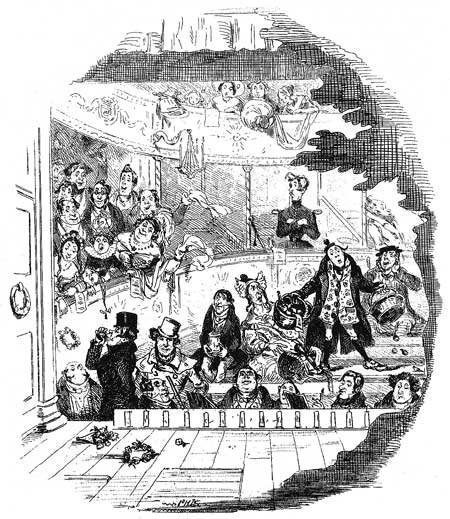

One theatre-goer, George Scharf recorded the scenic effects at Covent Garden and here is a sketch of what the play within the play scene in Hamlet looked like.

Unfortunately, Macready's management of Covent Garden was not successful but a few years later he was asked to take over management of the

Drury Lane Theatre, where he continued to restore the Bard's plays with full productions. Only three of Shakespeare's plays had not been restored when the actor-manager retired in 1851: Richard III, Taming of the Shrew and Romeo and Juliet.

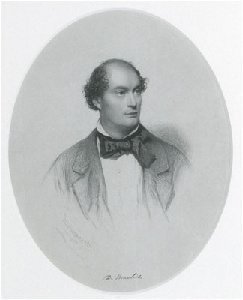

SAMUEL PHELPS

In 1843, a new Theatre Act allowed more theaters to do serious Shakespearean productions, and one of Macready's actors, Samuel Phelps took over the Sadler's Wells Theatre in Islington.

Phelps mounted productions of thirty-four Shakespearean plays including rarely done Richard III, Pericles and Anthony and Cleopatra. Phelps paid close attention to the integrity of the script, and the importance of each character, no matter the size of their role. Phelps would cast himself in supporting roles, giving other actors the leads, if he thought it would best serve the play.

For example, here we see him in the supporting role of Cardinal Wolsey in Henry VIII. The Sadler's Wells' stage was much smaller than the Drury Lane and Covent Garden theatres, and by using less (or no) scenery, Phelps was able to move the plays without interruptions for scenery changes. Phelps was able to achieve financial success producing Shakespeare, where Macready had failed. Dickens praised Phelps work, and an article about Shakespeare and Phelps in Household Words did much to bring Phelps's efforts to the attention of the London theater goers. It has been argued that Phelps's attention to all the parts of a play, helped Dickens develop his own attention to the parts of his novels, especially multiple plot lines.

CHARLES FECHTER

Another actor of the period that Dickens greatly admired was Charles Fechter. Fechter was also concerned with a unified conception of his plays. Dickens said Fechter's Hamlet was an "innovation in Art...not because of its picturesqueness...but because of its perfect consistency with itself." Theater critic Clement Scott said, "I sat spellbound under Fechter and seemed to understand Hamlet for the first time."

Fechter was also noted for performing Othello and Iago on alternating nights.

We also know that Dickens saw other great contemporary actors including Charles Kean, Priscilla Horton, and Charlotte Cushman.

ARTIST FRIENDS

Everybody has their own personal Shakespeare. My Shakespeare is different from Kevin's, is different from Su's, is different from Dickens's. These are based on what plays and studies we have read, productions and movies we have seen, as well as illustrations, photos of past productions and paintings of Shakespearean scenes. Dickens had many first hand experiences with the latter.

DANIEL MACLISE

Another very close friend with strong Shakespearean interests was the artist, Daniel Maclise.

Maclise is mainly known to Dickensians for his portrait of Charles Dickens in the National Portrait Gallery. The portrait is a bit idealized but said to be an excellent likeness. Maclise was one of the most popular artists in England during his lifetime. Some of his contemporaries called him, "out and away the greatest artist that ever lived."

He was born in Cork County, Ireland but came to London at an early age and quickly made a name for himself.

His painting of Malvolio Affecting the Count was shown at the Royal Academy Exhibition in 1829 when he was just twenty-two. Dickens became acquainted with Maclise in the mid 1830s and by the late 30s, Dickens, Forster and Maclise formed a "Trio Club" going everywhere together.

Maclise loved Shakespeare and painted scenes from the Bard's plays throughout his life.

The wrestling scene from As You Like It,

The Disenchantment of Bottom,

Othello and Desdemona,

Actress Priscilla Horton as Ariel. Dickens saw this production.

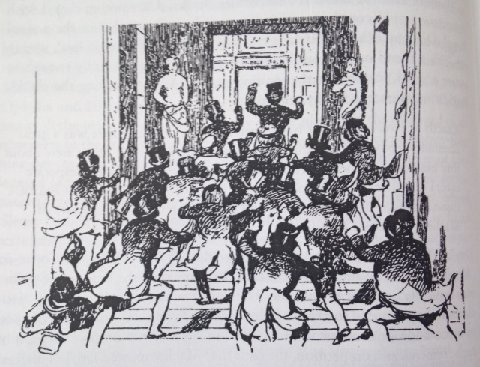

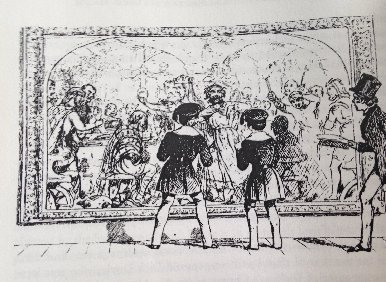

Maclise's Banquet Scene in Macbeth was a sensation. Dick Doyle, who years later was to illustrate editions of Dickens' Christmas books, was fifteen in 1840 when the Banquet Scene was shown at the Royal Academy, and wrote and drew in his journal,

"Exactly at twelve the door burst open and in we rushed, there was a great scramble to pay first and then off we darted up the stairs...

I rushed straight down the rooms till I came to McClises [sic] picture of Macbeth and there I stopped."

Now there were about a thousand works of art in this exhibition, but Doyle and many others dashed past hundreds of pictures so they could be the first to see Maclise's Macbeth.

Two years later, Maclise achieved even greater success with The Play Scene in Hamlet. This painting was the sensation of the 1842 Royal Academy Exhibition. Dickens wrote, "Maclise's picture from Hamlet is a tremendous production. There are things in it, which in their powerful thought, exceed anything I have seen beheld in painting."

A few minutes ago I showed you a sketch of this same scene as staged by Macready. Let's compare the staging with the painting.

They are almost the same, except for Hamlet's position. The shadow of the murderer in Maclise's painting suggests a cloak with a hood.

The shadow's arm looks like it is outstretched and pointing. A few Dickens scholars have pointed out that shortly afterward Dickens describes the Spirit of Christmas Yet to Come in a similar manner, and the spirits of The Chimes also have "draped and hooded heads."

MILLAIS

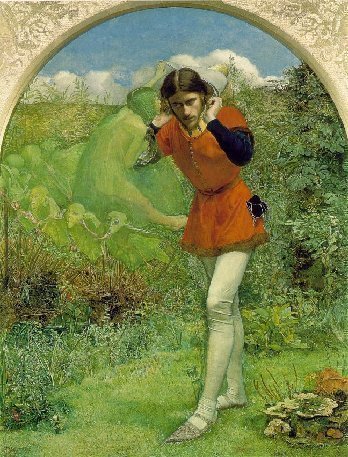

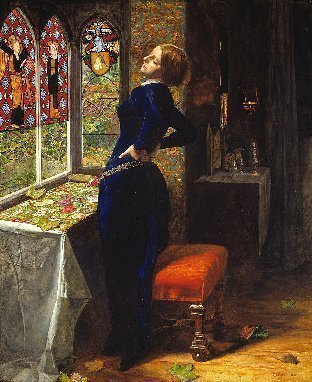

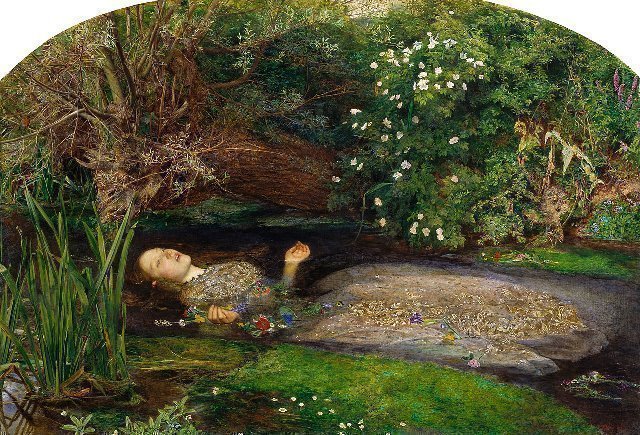

Dickens was also a friend with John Everett Millais, one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, who also loved to paint scenes from Shakespeare. Let's take a quick look at some of his Shakespearean paintings.

Rosalind disguised as Ganymede in As You Like It,

Ferdinand Lured by Ariel in The Tempest,

The Death of Romeo and Juliet,

The Princes in the Tower,

Mariana from Measure For Measure.

And unquestionably, his best known work...Ophelia. Looking at this masterpiece, one wonders if Dickens was thinking of it when he describes Rosa Bud's remembering the drowning of her mother. "Every fold and color in the pretty summer dress, and even the long wet hair, with scattered petals of ruined flowers still clinging to it, as the beloved young figure lay upon the bed."

SHAKESPEARE BIRTHPLACE

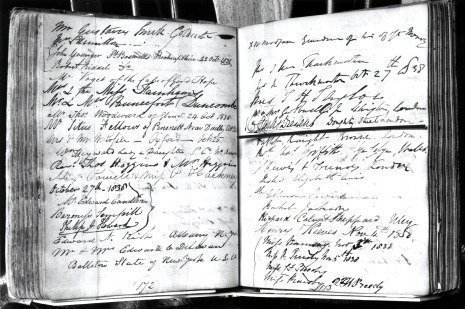

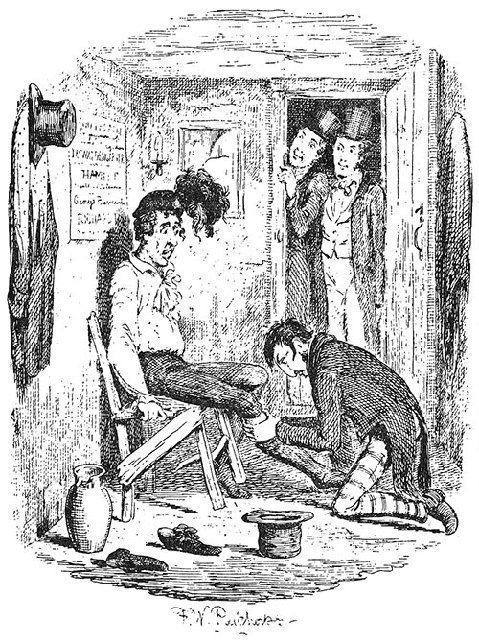

On October 27, 1838, Dickens and Hablot Browne visited the Shakespeare Birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon. They both signed the visitors' book.

Dickens was working on Nicholas Nickleby at the time, and shortly afterward the characters in the novel were discussing visiting the Birthplace.

Mrs Witterly says, "I find I take so much more interest in his plays, after having been to that dear little dull house he was born in! I don't know how it is, but after you've seen the place and written your name in the little book, somehow or other you seem to be inspired; it kindles up quite a fire within one."

"'I'm always ill after Shakespeare,' said Mrs Witterly. 'I scarcely exist the next day; I find the reaction so very great after a tragedy, my lord, and Shakespeare is such a delicious creature.'"

"'I think there must be something in the place,' said Mrs Nickleby, 'for, soon after I was married, I went to Stratford with my poor dear Mr Nickleby, in a post-chaise from Birmingham and after we had seen Shakespeare's tomb and birthplace, we went back to the inn there, where we slept that night, and I recollect that all night long I dreamt of nothing but a black gentleman, at full length, in plaster-of-Paris, with a lay-down collar tied with two tassels, leaning against a post and thinking; and when I woke in the morning and described him to Mr Nickleby, he said it was Shakespeare just as he had been when he was alive, which was very curious indeed. Stratford—Stratford,' continued Mrs Nickleby, considering. 'Yes, I am positive about that, because I recollect I was in the family way with my son Nicholas at the time, and I had been very much frightened by an Italian image boy that very morning. In fact, it was quite a mercy,' added Mrs Nickleby, 'that my son didn't turn out to be a Shakespeare, and what a dreadful thing that would have been!'"

The house was put up for sale in 1846 and a Shakespeare Birthday Committee was formed to raise the necessary 3,000 pounds to purchase the house. Dickens was instrumental in forming the committee and in raising the money.

The Shakespeare Birthday Committee changed its name to the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, which still administers the building and other properties in Stratford, as well as the museum, library and many programs. They have a "Shakespeare Hall of Fame" and Charles Dickens's name is third on the list – right after Ben Jonson and David Garrick.

MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR

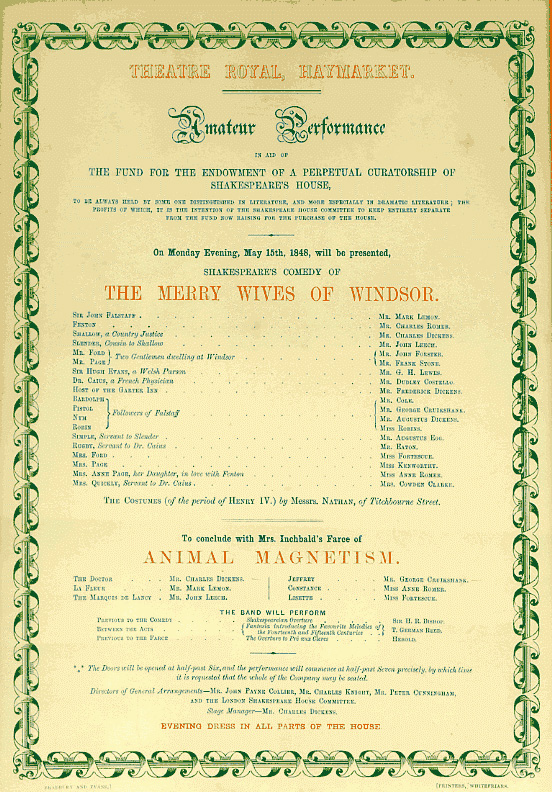

The playwright and actor Sheridan Knowles was a good friend of Dickens, and in the late 1840s Knowles was destitute and in need of employment. Dickens thought that Knowles would make an excellent curator for the Birthplace, and Dickens started a campaign to raise money for "the endowment of a perpetual curatorship", and he planned that the first curator would be Knowles. Dickens and his friends mounted two shows to be performed at the Haymarket to raise money for this project. One was The Merry Wives of Windsor (and the other was Every Man in His Humour). Knowles was given a government pension before the plays opened, but the shows must go on.

Of course Dickens threw himself fully into the production.

Forster wrote, "He was the life and soul of the whole affair...he took everything on himself, and did the whole of it without an effort. He was stage-director, very often stage carpenter, scene-arranger, property-man, prompter and bandmaster."

Mary Cowden Clarke reports that consideration was given as to what period the costumes should be...from the time of Henry IV, Henry V or from Shakespeare's own time, as that would be what the Globe's actors would have worn on stage. Dickens wrote, "I had arranged to dress the Merry Wives, in the legitimate costume of Henry IV – everybody from a picture."

Dickens brought in many of his friends to act in Merry Wives. Mark Lemon was Falstaff and Dickens himself played Justice Shallow. George Cruikshank and Mary Cowden Clarke, the compiler of The Shakespeare Concordance were in the cast.

Merry Wives opened at the Haymarket Theatre in London on May 15, 1848.

The show was taken to major cities around Great Britain, playing in Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Dickens considered bringing the Merry Wives to Stratford-upon-Avon, but since Birmingham was close to Stratford, Dickens feared that would affect attendance in Birmingham, and the idea was abandoned. Dickens did take the troop to see Shakespeare's grave in Stratford.

DICKENS AS ACTOR

So what was Dickens's performance as Justice Shallow like? Mary Cowden Clarke, who played Mistress Quickly, wrote,

"His impersonation was perfect; the old, still limbs, the senile stoop of the shoulders, the head bent with age, the feeble step, with a certain attempted smartness of carriage, characteristic of the conceited Justice of the Peace, were all assumed and maintained with wonderful accuracy; while the articulation, part lisp, part thickness of utterance, part of a kind of impeded sibilation like that of a voice that 'pipes and whistles in the sound' through loss of teeth, gave consummate effect to his mode of speech"

WRITER

Just as Mary Cowden Clarke just alluded to Jacques's speech in As You Like It, Dickens, as a writer, made thousands of allusions and references to the works of Shakespeare. It has been said that Dickens was unable to write without mentioning Shakespeare. Valerie Gager has over 120 pages of "Signs and tokens" in a catalog in her book, Shakespeare & Dickens, The Dynamics of Influence. The most allusions came from Macbeth, Hamlet, Othello and Julius Caesar. Professor Michael Slater has pointed out that the references to Hamlet are predominantly comic whereas those to Macbeth are predominantly connected with horror.

A good example of funny Hamlet allusions is in A Christmas Carol. Let's take a look at some of the Shakespearean references in the first stave of A Christmas Carol.

The very first paragraph says, "Old Marley was as dead as a door-nail." Shakespeare did not coin the phrase, but he did use it in Henry VI, part 2, where Jack Cade says, "Look on me well: I have eat no meat these five days; yet, come thou and thy five men, and if I do not leave you all as dead as a doornail, I pray God I may never eat grass more," and this is most likely where Dickens first encountered the phrase.

In the fourth paragraph, Dickens says, "There is no doubt that Marley was dead. This must be distinctly understood, or nothing wonderful can come of the story I am going to relate. If we were not perfectly convinced that Hamlet's Father died before the play began, there would be nothing more remarkable in his taking a stroll at night, in an easterly wind, upon his own ramparts, than there would be in any other middle-aged gentleman rashly turning out after dark in a breezy spot—say Saint Paul's Churchyard for instance—literally to astonish his son’s weak mind."

Michael Patrick Hearn tells us in The Annotated Christmas Carol that in the original manuscript, which is in the Morgan Library, Dickens went on to talk about Hamlet's character, "although perhaps you think that Hamlet's intellects were strong, I doubt it. If you could have such a son tomorrow, depend upon it, you would find him a poser. He would be a most impracticable fellow to deal with; and however creditable he might be to the family after his decease, he would prove a special encumbrance in his lifetime, trust me."

Mr Hearn points out that the passage is funny but doesn't advance the story and Dickens sensibly cut it from the manuscript.

Later in Stave One, the Ghost of Jacob Marley says Scrooge will be visited by the first spirit "when the bell tolls One.” The ghost of Hamlet's father also appears when the bell tolls One."

Some other memorable allusions to the Bard...

The Chimes, no doubt ,gets its title from Falstaff's line, "We have heard the chimes at midnight," as the title of the book refers to Trotty's relationship with time.

A chapter in The Mystery of Edwin Drood is entitled, "When Shall We Three Meet Again?"

The narrator in Bleak House says Lady Dedlock's, "Ariel has put a girdle of it round the whole earth, and it cannot be unclasped"

Ariel?

Hold on a moment. Ariel didn't say anything like that.

In Act II, Scene 1 of A Midsummer Night's Dream, Puck says, "I'll put a girdle round about the Earth In forty minutes."

Dickens actually made this mistake several times.

The Inimitable was not infallible.

The name of Dickens's journal, Household Words comes from King Henry V's St Crispin's Day speech.

"But he'll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day: then shall our names.

Familiar in his mouth as household words

Harry the king, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester,

Be in their flowing cups freshly remember'd."

In Tale of Two Cities. Sydney Carton's thoughts while he waits for death are very reminiscent of a famous passage in the Scottish play. "In a city dominated by the axe, alone at night, with natural sorrow rising in him for the sixty-three who had been that day put to death, and for to-morrow's victims then awaiting their doom in the prisons, and still of to-morrow's and to-morrow's, the chain of association that brought the words home...might have been easily found."

Dickens especially seemed to like Macbeth's final soliloquy. In a number of speeches for the General Theatrical Fund he talked about charity and working together with, "we all strut and fret our little hours upon this stage of life."

Dickens also borrows themes and plots. Think of how similar King Lear's relationship with Cordelia parallels father-daughter relationships in Dombey and Son, Old Curiosity Shop and Little Dorrit, and scholars have drawn parallels between the murder of Duncan in Macbeth to the murder of Nancy in Oliver Twist.

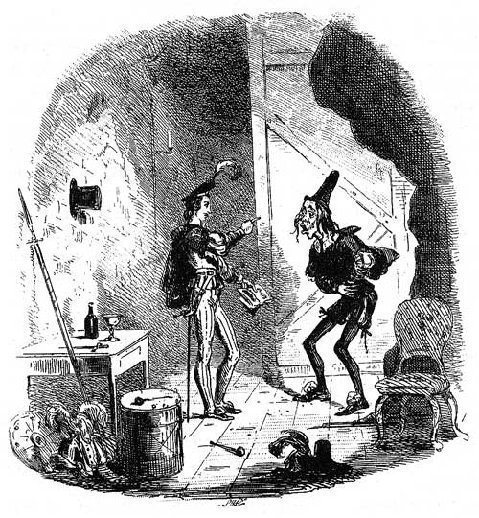

And there are whole sections of stories and novels devoted to Shakespeare. In "Mrs Joseph Porter" in Sketches by Boz, an amateur theatrical of the tragedy, Othello, turns into a comedy with two actors simultaneously ready to step on stage as Iago, the prompter losing his spectacles and sitting in the audience is Uncle Tom, who knows the script by heart, and corrects the mistakes of the actors as they miss their cues and lines, and to top it all, a special effect nearly burns the house down.

Nicholas Nickleby and Smike find themselves cast in a traveling company of actors' production of Romeo and Juliet; Nicholas as Romeo and Smike as the apothecary.

"They prospered well. The Romeo was received with hearty plaudits and unbounded favour, and Smike was pronounced unanimously, alike by audience and actors, the very prince and prodigy of Apothecaries."

The largest section of a story devoted to Shakespeare is Mr Wopsle's performance as Hamlet in chapter 31 of Great Expectations. Pip and Herbert find themselves laughing throughout the performance and are equally astonished with what they see backstage in Wopsle's dressing room.

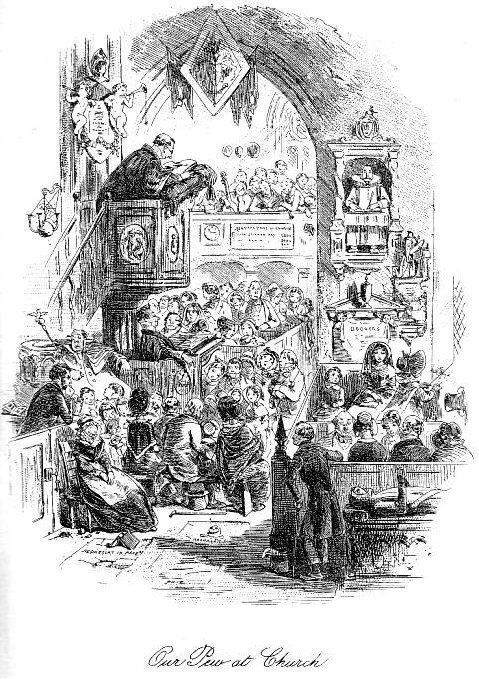

Allusions to Shakespeare might even be in the illustrations. Phiz drew the illustration, "Pew in Our Church," but surely Dickens had a hand in a copy of Shakespeare's funereal monument appearing above young David and his mother.

COMPARISONS

Michael Slater has said, "Dickens is the greatest novelist to have written in English as Shakespeare is the greatest poet." Many other scholars have tried to compare the two, with mixed results.

Some of the comparisons are obvious. Both Boz and the Bard lived during the reign of a long-lived queen. They wrote in literary forms that were relatively new and they helped change the forms. They were both collaborators but could create masterpieces with just their own genius. They both created wonderful characters and both loved metaphors.

They wrote to please the common man, and ended up creating great literature. Both are constantly studied by academics.

I wonder what Dickens would think of the studious academics of the Fellowship Conferences, the Dickensian magazine, the Dickens Universe at UCLA, my presentation right now, etc. He certainly satirized the academics spin on Shakespeare. Look at the Mr Curdle in Nicholas Nickleby who "had written a pamphlet of sixty-four pages, post octavo, on the character of the Nurse's deceased husband in Romeo and Juliet, with an inquiry whether he really had been a 'merry man' in his lifetime, or whether it was merely his widow's affectionate partiality that induced her so to report him. He had likewise proved, that by altering the received mode of punctuation, any one of Shakespeare's plays could be made quite different, and the sense completely changed; it is needless to say, therefore, that he was a great critic, and a very profound and most original thinker."

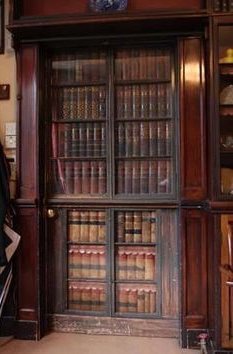

Also look at the famous bookcase in Dickens's study at Gadshill that is actually a door with fake books. Among the false titles that Dickens created are three books referencing Shakespeare. The titles satirize excessive biographical studies... Was Shakespeare's Father Merry?, Was Shakespeare's Mother Fair? and Had Shakespeare's Uncle a Singing Face?

MONUMENTS

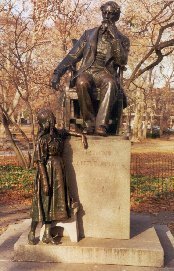

Dickens's will said he wanted no monuments and because of that, there are only three statues of Dickens in the world.

But there are quite a number of memorials to Shakespeare scattered around the globe, and Dickens would have been very familiar with several of them.

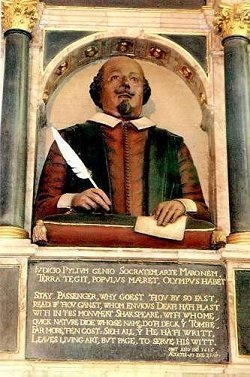

The first, of course, is the funerary monument of Shakespeare above his grave in Stratford. This was installed after his death in 1616 but before 1623, when the First Folio which mentions the monument, was published.

In 1740, the monument to Shakespeare in Westminster Abbey was installed. Dickens's grave is just a few feet in front of it.

When David Garrick took over the Drury Lane Theatre in 1747, he erected a statue of Shakespeare over the portico. Dickens commented on the statue frequently in his letters.

It was moved into the lobby during the 20th century.

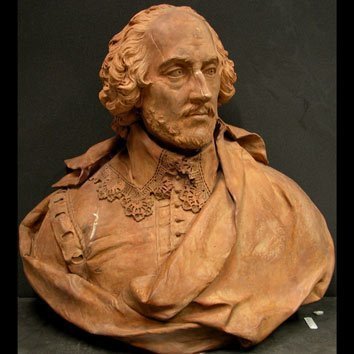

David Garrick built a small temple dedicated to Shakespeare in 1756 by the Thames in Hampton.

It housed a statue of Shakespeare by Roubiliac that is now in the British Museum.

The folly still stands, with a replica of the statue.

Roubiliac was also the sculptor of a bust of Shakespeare that is in the Garrick Club.

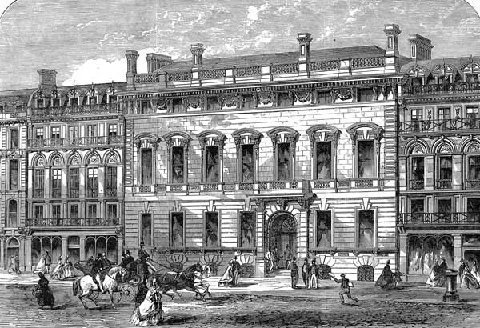

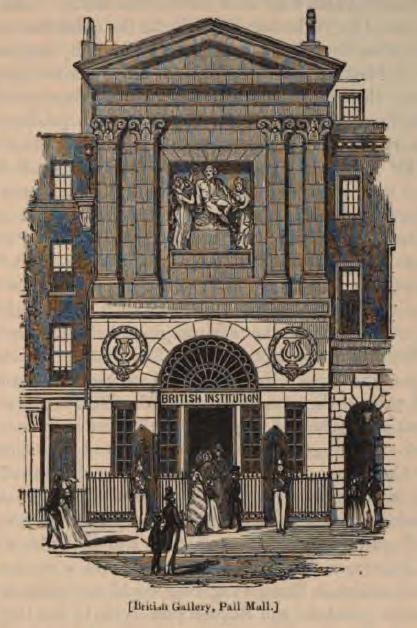

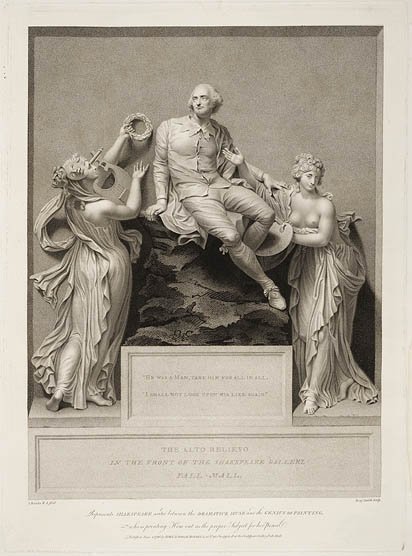

In 1789, publisher and engraver John Boydell opened his Shakespeare Gallery on Pall Mall. This was the first stage of a major publishing project, an illustrated Shakespeare, with established artists contributing paintings that would be engraved for insertion into what amounted to being the first coffee-table book. But first the artwork was on display in the Shakespeare Gallery with its imposing facade and a statue of Shakespeare Attended by Painting and Poetry. The building remained standing until 1868.

In the mid 1860s there was talk of erecting a statue of Shakespeare in Stratford. Dickens was against it.

But after Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery was demolished, the sculpture of Shakespeare Attended by Painting and Poetry was moved to Stratford and installed in a public garden.

Dickens said "Shakespeare has left his best monument in his works, and is best left without any other." Of course Dickens also said the same thing in his will regarding a monument or memorial to himself. Yet, he sat for portraits, busts and photographs.

There is one way that Dickens was immortalized where Shakespeare was not. In The Merry Wives of Windsor, Shakespeare wrote a phrase that will forever be associated with Charles Dickens.

"What the dickens"

We now know that Shakespeare didn't originate this phrase, but Dickens would not have known that. Dickens was very pleased thinking Shakespeare first said it.

He tried to return the favor. The Zephyr in The Pickwick Papers and Grandfather Smallweed in Bleak House both say,

"Hem! Shakespeare!"

But they are the only ones. No other character ever said it. And I can't recall ever hearing a Dickensian say "Hem, Shakespeare" It never caught on.

Let's try to popularize "Hem, Shakespeare!" Say it once a day.

Many thanks to Michael Slater, Michael Patrick Hearn, Janine Pollock of the Philadelphia Free Library, Florian Schweizer, Louisa Price and the Charles Dickens Museum for their invaluable help.

++++++++++++++++

SOURCES

The Annotated Christmas Carol, Michael Patrick Hearn, W.W. Norton, 2004

Charles Dickens, His Tragedy and Triumph, Edgar Johnson, Simon & Schuster, 1952

The Dickens Index, Nicholas Bentley, Michael Slater, Nina Burgis, 1990

Shakespeare & Dickens; The Dynamics of Influence, Valerie L. Gager

"Dickens and Shakespeare," Paul Schlicke, Japan Branch of the Dickens Fellowship, 2004

www.dickens.jp/archive/general/g-schlicke.pdf

"Dickens's Shakespeare," Michael Slater, Tale of Two Cities Conference, 2012 (Unpublished)

Dr Charlotte Mathieson, Dr Paul Edmondson and Professor Stanley Wells, discuss the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/dickens

"Shakespeare and Dickens; Soul Brothers"