Special Guests > Moskovitz: Punch and Dickens

Punch and Dickens

Charles Dickens' fascination with Punch and Judy shows

By Herb Moskovitz

Reprinted with permission of the authorPublished on this site May 30, 2015

Introduction

Dickens is noted for his wonderful descriptions, but his writings about the Punch and Judy puppets in Old Curiosity Shop are surprisingly brief. However, when one considers that his 19th century readers were as familiar with Punch and Judy as we are with Bart Simpson and Bugs Bunny, (both of whom have Mr Punch to thank for some of their characteristics) then it is quite understandable. In fact, Dickens often describes his scenes and characters by likening them to Punch. He does this in Sketches by Boz, Uncommercial Traveller, Little Dorrit, Our Mutual Friend, Dombey and Son and most notably in Old Curiosity Shop. He also notes seeing puppet shows in Pictures from Italy and regrets seeing none in New York in American Notes.

History of Punch and Judy

Although the average reader of Dickens in Victorian times would have known little of the history of Punch and Judy, a lot of information is available to us in the 21st Century in books and on the Internet.

I think we can say that we can trace the development of Punch to the early Greek theater although theater historians point out that there is no direct documentation. Greek playwrights such as Aristophenes often wrote about servants who were cleverer than their masters. Roman comedies are derived from the Greek and characters in plays by Plautus are ancestors of those in the Commedia Dell Arte - and later to Punch and Judy. If you have seen Stephen Sondheim's A Funny Thing Happened On The Way to the Forum, based on Plautus's plays, you are familiar with the clever servants, the befuddled master, the pompous authority figures, etc.

Many of the characters of the Commedia Dell– Arte are also on Punch's stage. - and in many of our performing arts entertainments of today. The Commedia's Pulcinella was a hunchbacked, hook nosed scoundrel.

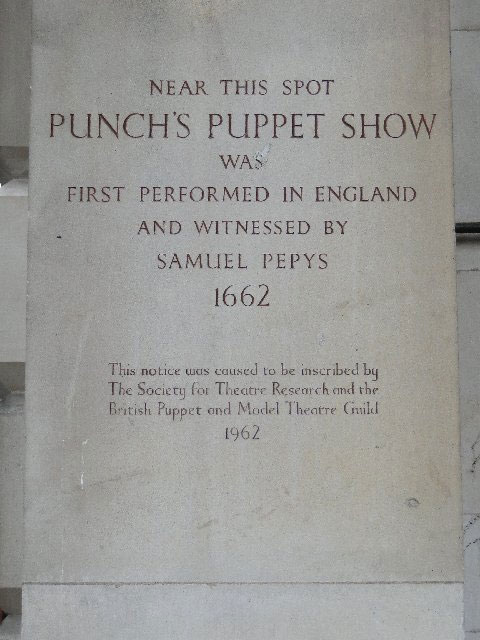

Samuel Pepys, that incurable diarist, records seeing a Punch and Judy show in Covent Garden on May 9th, 1662.

The puppeteer, Signor Bologna, had come from Naples with a marionette version of Pulcinella to perform in London as the city was celebrating the marriage of King Charles II. As Pulcinella traveled across Europe, the puppet was called Polichinelle in France and Punchinello when he arrived in England. Eventually the puppet became known as Punch. Signor Bologna's show was held in a tent with the puppeteer charging admission. Over the years Mr Punch was taken up by more and more puppeteers and somewhere around 1800 he became a hand puppet.

He then appeared on a small transportable stage, and usually entertained in the streets, with a hat passed around to collect money from the spectators. Other Commedia Dell Arte characters traveled with Punch. Another clown of the Commedia, Scaramouche becomes one of Punch's victims with the same name. Il Doctore becomes the doctor, the braggart soldier becomes the beadle – and later the policeman.

It was Harlequin who carried the cudgel in the Commedia, but Punch took it from him. Another clown named Joey, after Dickens's favorite, Joseph Grimaldi, was added to the cast in the early 19th Century.

And one day, the date lost to history, Mr Punch took a wife. Her name was Joan, but she was soon called Judy.

The first half of the 19th Century was Punch's golden age. A phrase, "Pleased as Punch" was first heard...Dickens used it in Hard Times, and when a group of radical writers founded a magazine in 1841 for their satirical humor, they called it Punch. Both the phrase and the magazine are still with us.

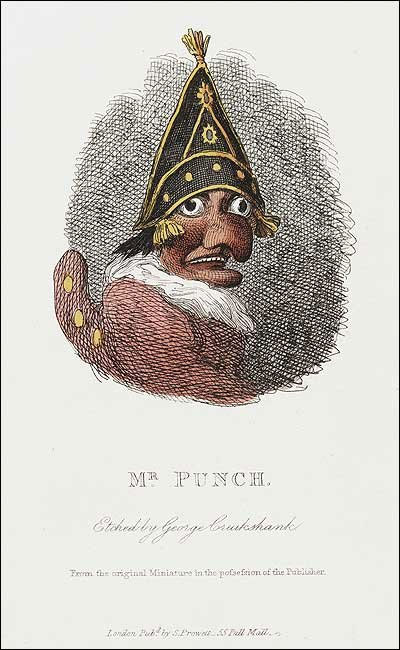

In 1828, Payne Collier transcribed a Punch and Judy show. George Cruikshank, who also illustrated Oliver Twist, drew the characters. This book gives us a wonderful look at Punch in his golden age.

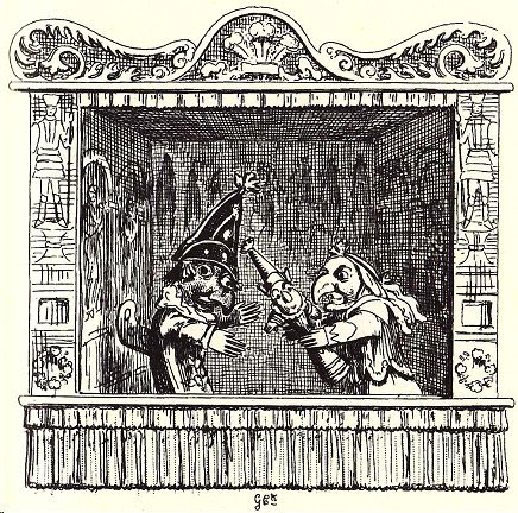

So what was a Punch and Judy show like? Every puppeteer had individual variations but in general Mr Punch appears and stays onstage the entire time. He may talk to the bottler, or Merry Andrew...a person working with the Puppeteer, who stands to the side of the booth. The Merry Andrew may have a live dog. The dog's name is always Toby. Punch may talk about eating swashages. He says, –Do you know why I call them swashages? Because I can't say sausages,– as he pronounces sausages perfectly. Punch then introduces his wife, Judy and their baby. He brags about his appearance and asks her "Aren't I handsome?" She responds sarcastically but he doesn't catch the sarcasm. When the baby won't stop crying he throws the baby out the window. Judy is outraged and gets a cudgel to teach Punch a lesson. He takes it away from her and after a ferocious battle Judy is killed and is also thrown out the window. Punch says, "That's the way to do it."

A beadle or policeman comes in to investigate and he too is soon dispatched. Punch says, "Tha's the way to do it."

Following the beadle are a doctor, a foreigner, a dragon or crocodile, the hangman, and many other characters - depending on the puppeteer. All are dispatched with –That's the way to do it!– In the end the devil himself appears and is killed as well. By now, the audience gleefully joins Punch when he says, "That's the way to do it!"

Dickens and Puppets

Although Dickens writes much about the Punch and Judy men in Old Curiosity Shop, he never describes their Punch and Judy show. He concentrates instead on the backstage lives of the Punch and Judy men, Codlin and Short:

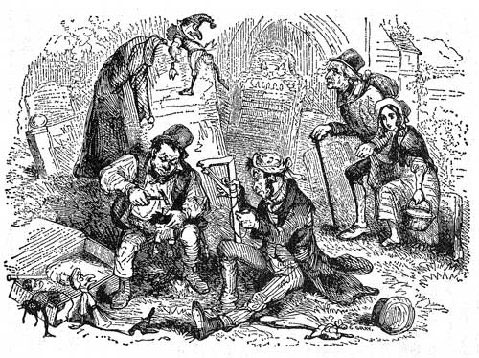

They were two men who were seated in easy attitudes upon the grass, and so busily engaged as to be at first unconscious of intruders. It was not difficult to divine that they were of a class of itinerant showmen--exhibitors of the freaks of Punch--for, perched cross-legged upon a tombstone behind them, was a figure of that hero himself, his nose and chin as hooked and his face as beaming as usual. Perhaps his imperturbable character was never more strikingly developed, for he preserved his usual equable smile notwithstanding that his body was dangling in a most uncomfortable position, all loose and limp and shapeless, while his long peaked cap, unequally balanced against his exceedingly slight legs, threatened every instant to bring him toppling down.

In part scattered upon the ground at the feet of the two men, and in part jumbled together in a long flat box, were the other persons of the Drama. The hero's wife and one child, the hobby-horse, the doctor, the foreign gentleman who not being familiar with the language is unable in the representation to express his ideas otherwise than by the utterance of the word 'Shallabalah' three distinct times, the radical neighbour who will by no means admit that a tin bell is an organ, the executioner, and the devil, were all here. Their owners had evidently come to that spot to make some needful repairs in the stage arrangements, for one of them was engaged in binding together a small gallows with thread, while the other was intent upon fixing a new black wig, with the aid of a small hammer and some tacks, upon the head of the radical neighbour, who had been beaten bald.

Quick footnote: There was a famous family of Punch puppeteers in Liverpool named Codman...Although Codlin and Short are minor characters, they do play an important part in the plot, and they direct the reader's awareness to Dickens's deliberate imagining of what kind of character would be created if one brought a truly evil Mr Punch to life. The answer is Daniel Quilp.

Dickens describes Quilp as a misshapen, hook-nosed dwarf, with a "ghastly smile, which, appearing to be the mere result of habit and to have no connexion with any mirthful or complacent feeling..."

Although Quilp does not beat his wife, he certainly mistreats her (and her mother). Quilp "performed so many horrifying and uncommon acts that the women were nearly frightened out of their wits, and began to doubt if he were really a human creature."

Remember what I said about Punch asking Judy if he were handsome? At one point Quilp says: "'Mrs Quilp!...Am I nice to look at? Should I be the handsomest creature in the world if I had but whiskers? Am I quite a lady's man as it is -- am I, Mrs Quilp?' Mrs Quilp dutifully replied, 'Yes, Quilp'; and fascinated by his gaze, remained looking timidly at him, while he treated her with a succession of such hostile grimaces, as none but himself and nightmares had the power of assuming. During the whole of that performance, which was somewhat of the longest, he preserved a dead silence, except when, by an unexpected skip or leap, he made his wife start backward with an irrepressible shriek. Then he chuckled."

But if Quilp does not wield a cudgel towards Mrs Quilp, he is no stranger to the weapon. Fighting two boys "... the dwarf flourished his cudgel, and dancing around the combatants and treading upon them and skipping over them, in a kind of frenzy, laid about him, now on one and now on the other, in a most desperate manner, always aiming at their heads and dealing such blows as none but the veriest little savage would have inflicted." Doesn't that sound just like Punch?

The Recreation Department's Punch and Judy

When I started to work for the Philadelphia Recreation Department, my colleague, Elaine Evans, suggested we create a Punch and Judy show, which we would take around to the different playgrounds. We made a set of Punch and Judy puppets, plus a baby, Scaramouche, doctor, beadle, policeman, hangman, horse, dragon and devil. We chose to break away from tradition in only one way. We chose to paint the characters' faces with bright primary and secondary colors. Since we would be going into neighborhoods of many different ethnic backgrounds, we did not want our puppets to be of any identifiable race. We followed the shows with workshops for the recreation leaders teaching puppet construction and manipulation. The puppetry program was very successful and for a number of years many kids from different playgrounds got free admission to the Zoo because they would do a puppet show near the Impala fountain.

Punch men are traditionally called "Professors," and often assume an Italian name. Since I had become a Punch and Judy man, you can now call me "Professor" – "Professor Umberto Moskovitillini" will do very nicely, thank you.

One time, after one of my shows, we had a woman come over and complain that we were destroying valuable antique puppets. I told her the "antiques" were five months old. But more serious objections were raised once about the violence. We told the complaining woman that we grew up with Punch and Judy and we thought we turned out ok. But we were aware, especially in the 1970s, that violence in children's entertainment was being studied as a possible problem.

If it is a problem, it is not a new one.

Disapproval of Punch and Judy

In 1749, Henry Fielding's Tom Jones meets an itinerant Punch and Judy man who says he has removed Punch and Judy and their violence from his puppet show and made it a "moral and refined" show. "I would by no means degrade the ingenuity of your profession," answered Jones, "but I should have been glad to have seen my old acquaintance master Punch, for all that; and so far from improving, I think, by leaving out him and his merry wife Joan, you have spoiled your puppet-show."

In the late 1840s Dickens received a letter asking for his help to "ban" the devil's work: Punch and Judy! The author of the letter must have been extremely disappointed with Dickens's response:

"In my opinion the Street Punch is one of those extravagant reliefs from the realities of life which would lose its hold upon the people if it were made moral and instructive. I regard it as quite harmless and as an outrageous joke which no one in existence would think of regarding as an incentive to any kind of action or as a model for any kind of conduct. It is possible, I think, that one secret source of pleasure very generally derived from this performance is the satisfaction the spectator feels in the circumstances that likenesses of men and women can be so knocked about without any pain or suffering."