Charles Dickens'

A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol in Prose - Being a Ghost Story of Christmas

A Christmas Carol - Published in one volume - Dec 1843

Plot

(contains spoilers)Ebenezer Scrooge is a penny-pinching miser in the first degree. He cares nothing for the people around him and mankind exists only for the money that can be made through exploitation and intimidation. He particularly detests Christmas which he views as 'a time for finding yourself a year older, and not an hour richer'. Scrooge is visited, on Christmas Eve, by the ghost of his former partner Jacob Marley who died seven Christmas Eves ago.

Marley, a miser from the same mold as Scrooge, is suffering the consequences in the afterlife and hopes to help Scrooge avoid his fate. He tells Scrooge that he will be haunted by three spirits. These three spirits, the ghosts of Christmas past, present,

and future, succeed in showing Scrooge the error of his ways. His glorious reformation complete, Christmas morning finds Scrooge sending a Christmas turkey to his long-suffering clerk, Bob Cratchit, and spending Christmas day in the company of his nephew, Fred, whom he had earlier spurned.Scrooge's new-found benevolence continues as he raises Cratchit's salary and vows to assist his family, which includes Bob's crippled son, Tiny Tim. In the end Dickens reports that Scrooge became "as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew" (Christmas Books-A Christmas Carol, p. 76).

Complete List of Characters:

Character descriptions contain spoilersA Christmas Carol Links:

Dickens and ChristmasDickens' Christmas Books

Dickens A Christmas Carol reading text

Thackeray on A Christmas Carol

Download A Christmas Carol in a text file

The Second Greatest Christmas Story Ever Told - By Thomas J. Burns (Originally published in Reader's Digest, December 1989)

SparkNotes - A Christmas Carol

Original Illustrations

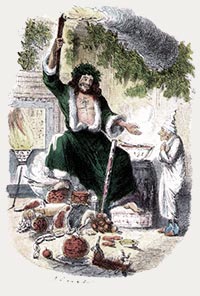

John Leech provided eight illustrations for A Christmas Carol. Four woodcuts and four hand colored etchings:

A Christmas Carol: The Films and the Players

(IMDB)

My Favorite Film Version of A Christmas Carol

Scrooge's grave at St. Chad's churchyard

My favorite film version of A Christmas Carol is the 1984 made-for-TV version starring George C. Scott as Ebenezer Scrooge. Faithful to Dickens' original with much of the dialogue lifted right out of the book, this version includes an excellent cast: Susannah York, Roger Rees, David Warner, and Edward Woodward, supporting the cranky Scott who is perfect as Scrooge.

The film was shot in locations in and around the town of Shrewsbury, England and has the gritty look and feel of early nineteenth-century London. Scrooge's grave from the film can still be seen in the graveyard of St Chad's church.

Fifteen Bob a Week

The miserly Scrooge paid his clerk, Bob Cratchit, a weekly salary of fifteen shillings (cockney slang for shilling was "bob"). Bob "pocketed on Saturdays but fifteen copies of his Christian name" (Christmas Books-A Christmas Carol, p. 43).

The miserly Scrooge paid his clerk, Bob Cratchit, a weekly salary of fifteen shillings (cockney slang for shilling was "bob"). Bob "pocketed on Saturdays but fifteen copies of his Christian name" (Christmas Books-A Christmas Carol, p. 43).

According to C. Z. Barnett in his play A Christmas Carol or The Miser's Warning (1844) Cratchit would have spent a week's wages to buy the ingredients for the Christmas feast: seven shillings for the goose, five for the pudding, and three for the onions, sage and oranges.

Ignorance and Want

One major theme in A Christmas Carol was rooted in Dickens' observations of the plight of the children of London's poor. It has been said of the times that sex was the only affordable pleasure for the poor; the result was thousands of children living in unimaginable poverty, filth, and disease.

In 1839 nearly half of all funerals in London were for children under the age of ten (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 384). Those who survived grew up without education or resource and virtually no chance to escape the cycle of poverty. Dickens felt that this vicious circle could only be broken through education and became interested in the Ragged Schools in London.Ragged Schools were free schools, run through charity, in which the poorest children received religious instruction and a rudimentary education. Dickens generally applauded the work of these schools although he disapproved of introducing religious doctrine at the expense of a practical education which would help the pupil become a self-sufficient member of society (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 406-407). Despite the availability of these schools, most poor children remained uneducated due to the demand for child labor and the apathy of parents, wretchedly poor and uneducated themselves.

Dickens introduces these children in A Christmas Carol through the allegorical twins, Ignorance and Want. The Ghost of Christmas Present shows them, wretched and almost animal in appearance, to Scrooge with the warning: "This boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want. Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased" (Christmas Books-A Christmas Carol, p. 57).

Charles Dickens continued to support education for the poor through his works but compulsory education for all did not come about until 1870, the year of Dickens' death.

The Death of Tiny Tim

Death of Tiny Tim-by Sol Eytinge 1869

Michael Patrick Hearn, in his book The Annotated Christmas Carol, notes that Clarence Cook, reporting for the New York Tribune after attending a public reading by Dickens of A Christmas Carol in Boston in 1867, noted that the passage of Tiny Tim's death "brought out so many pocket handkerchiefs that it looked as if a snow-storm had somehow gotten into the hall without tickets" (Hearn, 2004, p. 249, n. 2).

Dead as a Doornail

Dickens begins A Christmas Carol by impressing upon the reader that Jacob Marley was dead. In fact, he was "dead as a doornail." He goes on to question this well-known simile:

"Mind! I don't mean to say that I know, of my own knowledge, what there is particularly dead about a door-nail. I might have been inclined, myself, to regard a coffin-nail as the deadest piece of ironmongery in the trade. But the wisdom of our ancestors is in the simile; and my unhallowed hands shall not disturb it, or the Country's done for. You will therefore permit me to repeat, emphatically, that Marley was as dead as a door-nail" (Christmas Books-A Christmas Carol, p. 7).

The phrase "dead as a doornail" appears as early as the fourteenth-century in The Vision of Piers Plowman and later in Shakespeare's Henry IV. However, the origin of the phrase is unknown. One possible explanation is that doors were built using only wood boards and hand forged nails, the nails were long enough to dead nail the (vertical)  wooden panels and (horizontal) stretcher boards securely together, so they would not easily pull apart. This was done by pounding the protruding point of the nail over and down into the wood. A nail that was bent in this fashion (and thus not easily pulled out) was said to be "dead", thus "dead as a doornail." (Wiktionary)

wooden panels and (horizontal) stretcher boards securely together, so they would not easily pull apart. This was done by pounding the protruding point of the nail over and down into the wood. A nail that was bent in this fashion (and thus not easily pulled out) was said to be "dead", thus "dead as a doornail." (Wiktionary)

Thackeray on the Carol

William Makepeace Thackeray in Fraser's Magazine (February 1844) pronounced the book, "a national benefit and to every man or woman who reads it, a personal kindness. The last two people I heard speak of it were women; neither knew the other, or the author, and both said, by way of criticism, 'God bless him!'"

William Makepeace Thackeray in Fraser's Magazine (February 1844) pronounced the book, "a national benefit and to every man or woman who reads it, a personal kindness. The last two people I heard speak of it were women; neither knew the other, or the author, and both said, by way of criticism, 'God bless him!'"

Thackeray wrote about Tiny Tim, "There is not a reader in England but that little creature will be a bond of union between the author and him; and he will say of Charles Dickens, as the woman just now, 'GOD BLESS HIM!' What a feeling this is for a writer to inspire, and what a reward to reap!" (Frasers, 1844, p. 167-169 signed with the initials M.A.T. for Thackeray's pen name Michael Angelo Titmarsh).

Sabbatarianism

Sabbatarianism, the Christian doctrine of strict observance of Sunday as a holy day reserved for worship, was attacked by Dickens throughout his life. In 1836 he published the pamphlet Sunday Under Three Heads in opposition to a Bill that would have extended already strict limitations to Sunday recreation. Dickens felt that these Bills were an attempt by the upper classes to control the lives of the lower classes disguised as religious piety (Slater, 2009, p. 70-71). He argued that Sunday was the only day that the poor and working classes could enjoy simple pleasures that the upper and middle classes enjoyed all week. In A Christmas CarolDickens again voices these concerns through this exchange between Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Present:

In 1836 he published the pamphlet Sunday Under Three Heads in opposition to a Bill that would have extended already strict limitations to Sunday recreation. Dickens felt that these Bills were an attempt by the upper classes to control the lives of the lower classes disguised as religious piety (Slater, 2009, p. 70-71). He argued that Sunday was the only day that the poor and working classes could enjoy simple pleasures that the upper and middle classes enjoyed all week. In A Christmas CarolDickens again voices these concerns through this exchange between Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Present:

"Spirit," said Scrooge, after a moment's thought, "I wonder you, of all the beings in the many worlds about us, should desire to cramp these people's opportunities of innocent enjoyment."

"I!" cried the Spirit.

"You would deprive them of their means of dining every seventh day, often the only day on which they can be said to dine at all," said Scrooge. "Wouldn't you?"

"I!" cried the Spirit.

"You seek to close these places on the Seventh Day," said Scrooge. "And it comes to the same thing."

"I seek!" exclaimed the Spirit.

"Forgive me if I am wrong. It has been done in your name, or at least in that of your family," said Scrooge.

"There are some upon this earth of yours," returned the Spirit, "who lay claim to know us, and who do their deeds of passion, pride, ill-will, hatred, envy, bigotry, and selfishness in our name, who are as strange to us and all our kith and kin, as if they had never lived. Remember that, and charge their doings on themselves, not us" (Christmas Books-A Christmas Carol, p. 43.)

Cooking the Cratchit's Christmas Goose

The homes of the poor were equipped with open fireplaces for heat and cooking but not with ovens. Thus many, like the Cratchits, took their Christmas goose or turkey to the baker's shop. Bakers were forbidden to sell on Sundays and holidays but would open their shops on these days to the poor and bake their dinners for a small fee. Dickens tells of Master Peter Cratchit and the two younger Cratchits going to fetch their Christmas goose from the bakers (Hearn, 2004, p. 91-92, n. 28).

The homes of the poor were equipped with open fireplaces for heat and cooking but not with ovens. Thus many, like the Cratchits, took their Christmas goose or turkey to the baker's shop. Bakers were forbidden to sell on Sundays and holidays but would open their shops on these days to the poor and bake their dinners for a small fee. Dickens tells of Master Peter Cratchit and the two younger Cratchits going to fetch their Christmas goose from the bakers (Hearn, 2004, p. 91-92, n. 28).

Actress Liz Smith (Born: Betty Gleadle December 11, 1921 in Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire, England) has the distinction of playing Mrs Dilber in two versions of A Christmas Carol: the 1984 version starring George C. Scott, and the 1999 version starring Patrick Stewart.

Actress Liz Smith (Born: Betty Gleadle December 11, 1921 in Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire, England) has the distinction of playing Mrs Dilber in two versions of A Christmas Carol: the 1984 version starring George C. Scott, and the 1999 version starring Patrick Stewart.

Preface to the Original Edition

A Christmas CarolI have endeavoured in this Ghostly little book, to raise the Ghost of an Idea, which shall not put my readers out of humour with themselves, with each other, with the season, or with me. May it haunt their houses pleasantly, and no one wish to lay it.

Their faithful Friend and Servant,

C. D.

December, 1843.

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. MA 97.

- Sketches by Boz |

- Pickwick |

- Oliver Twist |

- Nickleby |

- Old Curiosity Shop |

- Barnaby Rudge |

- Chuzzlewit |

- Christmas Carol |

- Christmas Books |

- American Notes |

- Pictures from Italy |

- Dombey and Son |

- Copperfield |

- Bleak House |

- Hard Times |

- Little Dorrit |

- Tale of Two Cities |

- Great Expectations |

- Our Mutual Friend |

- Edwin Drood |

- Minor Works |

- The Uncommercial Traveller |

- Short Stories

In came a fiddler with a music book, and went up to the lofty desk, and made an orchestra of it, and tuned like fifty stomach-aches. In came Mrs Fezziwig, one vast substantial smile. In came the three Miss Fezziwigs, beaming and lovable. In came the six young followers whose hearts they broke"

In came a fiddler with a music book, and went up to the lofty desk, and made an orchestra of it, and tuned like fifty stomach-aches. In came Mrs Fezziwig, one vast substantial smile. In came the three Miss Fezziwigs, beaming and lovable. In came the six young followers whose hearts they broke"

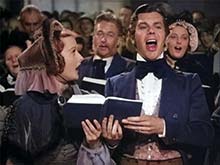

Dickens called his little Christmas book a carol; carol being a song or ballad of joy celebrating the birth of Christ. He carries the pretense further by calling the chapters staves; a stave being an archaic form of stanza or verse of a song. He used similar schemes in two subsequent Christmas books:

Dickens called his little Christmas book a carol; carol being a song or ballad of joy celebrating the birth of Christ. He carries the pretense further by calling the chapters staves; a stave being an archaic form of stanza or verse of a song. He used similar schemes in two subsequent Christmas books: