Charles Dickens in America

Explore Charles Dickens' travels in America and Canada

First American Visit - 1842See second American visit

On January 3, 1842 Charles Dickens, a month shy of his 30th birthday, sailed from Liverpool on the steamship Britannia bound for America.

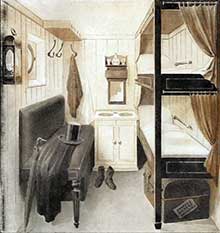

Dickens was at the height of his popularity on both sides of the Atlantic and, securing approval from his publishers, Chapman and Hall (Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 196), determined to visit the young nation to see for himself this haven for the oppressed which had righted all the wrongs of the Old World (Johnson, 1952, p. 352-353). The voyage out, accompanied by his wife, Catherine, and her maid, Anne Brown, proved to be one of the stormiest in years and his cabin aboard the Britannia proved to be so small that Dickens quipped that their portmanteaux could "no more be got in at the door, not to say stowed away, than a giraffe could be forced into a flowerpot" (American Notes, p. 1).American Notes - Charles Dickens' account of the 1842 trip to America

Buy it at Amazon.com

The violent seas on the journey can best be described by Dickens' comical account of trying to administer a little brandy to his wife and her traveling companions to calm their fears:

They, and the handmaid before mentioned, being in such ecstasies of fear that I scarcely knew what to do with them, I naturally bethought myself of some restorative or comfortable cordial; and nothing better occurring to me, at the moment, than hot brandy-and-water, I procured a tumblerful without delay. It being impossible to stand or sit without holding on, they were all heaped together in one corner of a long sofa -- a fixture, extending entirely across the cabin -- where they clung to each other in momentary expectation of being drowned. When I approached this place with my specific, and was about to administer it, with many consolatory expressions, to the nearest sufferer, what was my dismay to see them all roll slowly down to the other end! And when I staggered to that end, and held out the glass once more, how immensely baffled were my good intentions by the ship giving another lurch, and their all rolling back again! I suppose I dodged them up and down this sofa for at least a quarter of an hour, without reaching them once; and, by the time I did catch them, the brandy-and-water was diminished, by constant spilling, to a tea-spoonful (American Notes, p. 16).

Newspaper accounts of Charles Dickens' 1842 visit to America

Arriving in Boston on January 22, 1842 Charles Dickens was at once mobbed and generally given the adulation afforded four other young Englishmen who would invade America more than a century later.

Dickens at first reveled in the attention but soon the never-ending demand of his time began to wear on his enthusiasm. He complained in a letter to his friend John Forster "I can do nothing that I want to do, go nowhere where I want to go, and see nothing that I want to see. If I turn into the street, I am followed by a multitude" (Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 229).One of the things on Dickens' agenda for the trip to America was to try to put forth the idea of international copyright. Dickens' works were routinely pirated in America and for the most part he received not a penny for his writing there. Dickens argued that American authors would benefit also as they were pirated in Europe but these arguments generally fell on deaf ears. His continued campaign on the subject caused a furor in the American press, accusing Dickens of being a merenary scoundrel, and coming to America for the express purpose of monetary gain (Johnson, 1952, p. 380-382). Indeed, there would be no international copyright law until 1891 (Wikipedia). Dickens did not touch on the tempest caused by his argument for international copyright in American Notes but revealed the controversy in this letter to his friend John Forster.

Laura Bridgman

While in the Boston area Charles Dickens visited the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts School for the Blind where he observed Laura Bridgman (1829-1889), a blind and deaf girl Dickens chronicled in American Notes. Laura's remarkable education through the teaching of Samuel Gridley Howe, director of the school (Payne, 1927, p. 61-63). 40 years later Captain Arthur Keller and his wife, Kate, were inspired by Dickens' account of Laura Bridgman and the Perkins Institution (Keller, 1904, p. 17). The Keller's blind and deaf daughter, Helen Keller (1880-1968), also received part of her remarkable education at the Perkins school through Anne Sullivan, a visually impaired teacher and recent graduate of the institution (Keller, 1904, p. 21).

a blind and deaf girl Dickens chronicled in American Notes. Laura's remarkable education through the teaching of Samuel Gridley Howe, director of the school (Payne, 1927, p. 61-63). 40 years later Captain Arthur Keller and his wife, Kate, were inspired by Dickens' account of Laura Bridgman and the Perkins Institution (Keller, 1904, p. 17). The Keller's blind and deaf daughter, Helen Keller (1880-1968), also received part of her remarkable education at the Perkins school through Anne Sullivan, a visually impaired teacher and recent graduate of the institution (Keller, 1904, p. 21).Eager to compare the public institutions of America to those in Britain, visits to prisons, hospitals for the insane, orphanages, and schools for blind and deaf children were high on his list of places to see in almost every city he visited. He also toured factories such as the industrial mills of Lowell, Massachusetts (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 347). While in Washington he toured the White House, and met tenth US President John Tyler (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 360). Later in his visit he toured a prairie in Illinois, and a Shaker village in New York (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 363-368).

Dickens wanted to see the South and observe slavery first hand. His initial plan was to go to Charleston but because of the heat and the length of the trip he settled for Richmond, Virginia. He was revolted by what he saw in Richmond, both by the condition of the slaves themselves and by the whites' attitudes towards slavery (Johnson, 1952, p. 402-403). In American Notes, the book written after he returned to England describing his American visit, he wrote scathingly about the institution of slavery, citing newspaper accounts of runaway slaves horribly disfigured by their cruel masters (American Notes, p. 228-243). From Richmond Dickens returned to Baltimore, via Washington, and started a trek westward to St. Louis. Traveling by riverboat and stagecoach the Dickens entourage, which included Dickens, his wife Catherine, Kate's maid, Anne Brown, and George Putnam, Charles' traveling secretary, endured quite an adventure. Gaining anonymity and more personal freedom the further west they went, Dickens' power of observation provides a very entertaining and enlightening view of early America (Johnson, 1952, p. 403-425).

Charles Dickens came away from his American experience with a sense of disappointment. To his friend William Macready he wrote "this is not the republic I came to see; this is not the republic of my imagination" (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 156). On returning to England Dickens began an account of his American trip which he completed in four months. Not only did Dickens attack slavery in American Notes, he also attacked the American press whom he blamed for the American's lack of general information. In Dickens' next novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, he sends young Martin to America where he continues to vent his feelings for the young republic. American response to both books was extremely negative and passions flared. Dickens made amends during his second visit to America in 1867-68 with a conciliatory speech in New York.

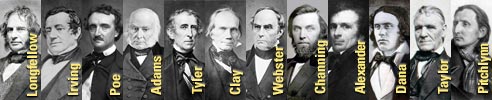

Presidents, Statesmen, Writers, and a Choctaw Indian Chief

The list of notable people that Dickens hobnobbed with during this trip reads like a who's who of mid-nineteenth century America. A few...

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882 - American poet known for Paul Revere's Ride, The Song of Hiawatha, and The Village Blacksmith. He was also a Professor of Modern Languages at Harvard College. Longfellow described Dickens: "He is a gay, free and easy character;-a fine bright face; blue eyes, long dark hair, and withal a slight dash of the Dick Swiveller in him" (Hilen, 1966, v. 2, p. 381).

Washington Irving (1783-1859) - American writer best known for Rip Van Winkle, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, and biographies of Muhammad and George Washington. Dickens had long admired Irving's writing. The two enjoyed each other's company during the American visit but relations between them cooled after Dickens published American Notes (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 351).

Edgar Allen Poe (1809-1849) - American writer and poet best known for The Raven, The Tell-Tale Heart, The Pit and the Pendulum, and Annabel Lee. Poe praised Dickens' The Old Curiosity Shop in a review for Graham's Magazine. Poe and Dickens met twice in Philadelphia during Dickens' stay there. Poe asked Dickens for help finding him a British publisher. Dickens did try but was unsuccessful and the relationship cooled (Slater, 2009, p. 184).

John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) - Sixth president of the US (1825-1929) and eldest son of second president John Adams. From 1831 to his death he served in the US House of Representatives. Dickens said of him "Adams is a fine old fellow-seventy-six years old, but with most surprising vigour, memory, readiness, and pluck" (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 133).

John Tyler (1790-1862) - Tenth president of the US whom Dickens met at the White House on March 10. At their meeting Tyler, welcoming Dickens, said that he was astonished to see so young a man. Dickens smiled and thought of returning the compliment but didn't; for the president looked too worn and tired to justify it (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 111).

Henry Clay (1777-1852 - American statesman who represented Kentucky in both the Senate and House of Representatives. Known as the 'Great Compromiser' for his work on the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Dickens described him as "one of the most agreeable and fascinating men I ever saw. He is tall and slim, with long, limp, gray hair—a good head—refined features—a bright eye—a good voice—and a manner more frank and captivating than I ever saw in any man, at all advanced in life. I was perfectly charmed with him" (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 117).

Daniel Webster (1782-1852 - Lawyer and statesman who served in the Senate and House of Representatives. He also served as Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Millard Fillmore. Called on Dickens in Washington. Dickens remarked on Webster's "feigning abstraction in the dreadful pressure of affairs of state; rubbing his forehead as one who was a-weary of the world" (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 134).

Dr William Ellery Channing (1780-1842) - Foremost Unitarian preacher in the US in the early nineteenth century. Pastor of the Federal Street Church in Boston and a fervent opponent of slavery. Dickens breakfasted with Channing on February 2 in Boston. Dickens wrote of him: "I was reluctantly obliged to forego the delight of hearing Dr Channing, who happened to preach that morning for the first time in a very long interval. I mention the name of this distinguished and accomplished man (with whom I soon afterwards had the pleasure of becoming personally acquainted), that I may have the gratification of recording my humble tribute of admiration and respect for his high abilities and character; and for the bold philanthropy with which he has ever opposed himself to that most hideous blot and foul disgrace – Slavery" (American Notes, p. 25-26).

Francis Alexander (1800-1880) - American portrait painter who painted Dickens during the visit to Boston. Apparently there were quite a few artists eager to paint Dickens' portrait in Boston but Alexander got the jump on them but taking a boat out to meet Dickens' ship in Boston Harbor. He then drove Dickens, Catherine, and her maid Anne Browne to their rooms at Tremont House. Alexander's student, George Washington Putnam, became Dickens' travelling secretary during the trip.

Richard Henry Dana Jr (1815-1882) - American lawyer and writer from Massachusetts. For health reasons he decided to go to sea as a merchant seaman aboard the brig Pilgrim which departed Boston in 1834. His memoir, Two Years Before the Mast, recounting the two-year voyage around Cape Horn to California, published in 1840, became an instant classic describing the lot of the common sailor and the early days of California and was said to influence the work of Herman Melville. Dickens reported to Forster that Dana "is a very nice fellow indeed; and in appearance not at all the man you would expect. He is short, mild-looking, and has a care-worn face" (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 38-39).

Edward Thompson Taylor (1793-1871) - Former seaman turned Methodist minister. He was known for peppering his eloquent sermons with nautical language and was said to be the inspiration for Melville's Father Mapple from Moby Dick. Dickens, on hearing 'Father Taylor' preach at his church Seamen's Bethal in Boston, described him: "He looked a weather-beaten hard-featured man, of about six or eight and fifty; with deep lines graven as it were into his face, dark hair, and a stern, keen eye. Yet the general character of his countenance was pleasant and agreeable" (American Notes, p. 57).

Peter Pitchlynn (1806-1881) - Chief of the Choctaw tribe and of Choctaw and Anglo-American ancestry. Dickens met Pitchlynn on the steamboat from Cincinnati to Louisville as he was returning from a stint in Washington representing his tribe in some negotiations with the government. Dickens described him in American Notes: "He was a remarkably handsome man; some years past forty, I should judge; with long black hair, an aquiline nose, broad cheek-bones, a sunburnt complexion, and a very bright, keen, dark, and piercing eye" (American Notes, p. 166).

Dickens Bust

Copy of Dexter's bust of Dickens given to the Dickens Museum in 1962 by Dexter's granddaughter. The original has been lost.

While in Boston in 1842 Dickens sat for a bust by artist Henry Dexter which is said to be very like the young Dickens. Dickens' secretary, George Washington Putnam, described the process:

"While Mr. Dickens ate his breakfast, read his letters, and dictated his answers, Dexter was watching with the utmost earnestness the play of every feature, and comparing his model with the original. Often during the meal he would come to Dickens with a solemn, business-like air, stoop down and look at him sideways, pass round and take a look at the other side of his face, and then go back to his model and work away for a few minutes; then come again and take another look and go back to his model; soon he would come again with his callipers and measure Dickens's nose, and go and try it on the nose of the model; then come again with the callipers and try the width of the temples, or the distance from the nose to the chin, and back again to his work, eagerly shaping and correcting his model. The whole soul of the artist was engaged in his task, and the result was a splendid bust of the great author. Mr. Dickens was highly pleased with it, and repeatedly alluded to it, during his stay, as a very successful work of art" (Putnam, 1870).

Second American Visit - 1867-68

In the late 1850s Charles Dickens began to contemplate a second visit to America, tempted by the money that he believed he could make by extending his reading tour, hugely successful in Britain, to the New World. The outbreak of the Civil War in America in 1861 put those plans on hold (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 865-866). After the war, renewed offers

Dickens by J. Gurney, New York 1867 from America of huge profits to be made if Dickens would read there. He decided to send his tour manager, George Dolby, to America to see first-hand what the financial prospects were and to begin to scout likely venues for a reading tour (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 997-998).

On Dolby's return, his glowing accounts of the money to be made convinced Dickens to go, despite questions of poor health and objections from his friend and advisor, John Forster. Dickens' argument for going was penned in what he called the "Case in a Nutshell" which he forwarded to Forster and other doubters (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 323-325).

The downside of such a venture, for Dickens, was that of leaving his mistress, Ellen Ternan, for an extended period. He began to devise schemes which would allow Ellen to accompany him. First he asked his daughter Mamie to go along to accompany Ellen, Mamie declined. He instructed Dolby to go ahead of him to America to make sure all was ready for the tour, and ask him to make careful inquiries as to whether or not Ellen could discreetly accompany him. Dolby cabled back "no" (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 1003-1005).

Dickens had still not given up. Prior to his departure for America he instucted his sub-editor at All the Year Round, W.H Wills, that on his arrival he would send a telegraph that should be forwarded as written to Ellen with a coded message instructing her to "come," or "don't come." Finally, seeing for himself that discreet accompaniment was impossible, he was forced to send "don't come" (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 1006).

Dickens arrived in Boston on November 19, 1867. Dolby, on visiting with "the Chief" on the evening of his arrival found Dickens in a depressed state of mind. It seems that the waiter had left the door to his sitting-room partially open during dinner so that visitors could gawk as him. This prompted him to quip angrily to Dolby that "These people have not in the least changed in the last five and twenty years—they are doing now exactly what they were doing then". His spirits, however, were soon bolstered by the report from Dolby on unprecedented ticket sales for the readings, not due to the monetary gain, but by the adulation it represented (Dolby, 1887, p. 158-159).

Although the readings were a remarkable success everywhere he went, his health was in rapid decline, and he suffered greatly during this trip. On several occasions Dolby feared that he would not be able to go on with an evening's reading. However, no shows were cancelled. Dickens quipped that "No man had a right to break an engagement with the public if he were able to be out of bed" (Dolby, 1887, p. 226-227).The original plan called for a visit to Chicago and as far west as St. Louis. Because of ill-health, and the fact that profits from the readings were already exceeding expectations, this idea was scrapped, and Dickens did not venture from the northeastern states (Slater, 2009, p. 580). He stayed for five months and gave 76 performances for which he earned an incredible £19,000 (Schlicke, 1999, p. 17). Mark Twain saw Dickens perform in January, 1868 at the Steinway Hall in New York and gave this report.

At a dinner in his honor in New York on April 18, 1868 Dickens, alluding to negative aspects of the 1842 trip, noted that both he and America had undergone considerable change since his last visit. He commented on the excellent treatment he had received from everyone he came in contact with on this trip and vowed to include these words as an appendix to every copy of the two books in which he refers to America (American Notes and Martin Chuzzlewit) (Johnson, 1952, p. 1092-1094).

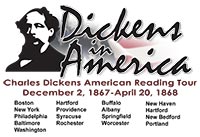

Charles Dickens' 1867-68 American Reading Tour

Map of Dickens' 1867-68 American reading tour along with a table showing dates, cities, passages read, interesting notes and photos, and references.

Map of Dickens' 1867-68 American reading tour along with a table showing dates, cities, passages read, interesting notes and photos, and references.

The tour required several trips between Boston and New York on the recently completed Shore Line Railway, an interesting mix of rail and train ferry.

Near the end of Charles Dickens' 1842 travels in North America he observed, on a steamboat between Quebec and Montreal, emigrants from England crowded between decks. He recorded his thoughts, in this beautiful passage in

Near the end of Charles Dickens' 1842 travels in North America he observed, on a steamboat between Quebec and Montreal, emigrants from England crowded between decks. He recorded his thoughts, in this beautiful passage in  During his 1842 American trip Dickens took his first ride on an American railway on February 3 on a trip from Boston to Lowell, Massachusetts and described the state of American railroads in its infancy.

During his 1842 American trip Dickens took his first ride on an American railway on February 3 on a trip from Boston to Lowell, Massachusetts and described the state of American railroads in its infancy. After a harrowing trip to America by steamship Dickens determined to return to Britain under sail. He left New York on June 7 and arrived in Liverpool on June 29. The ship, American packet sailing vessel George Washington, was built at New Bedford, Massachusetts in 1832 and regularly made the trip from New York to Liverpool. In 1845 she was converted to a whaler. In this last chapter of

After a harrowing trip to America by steamship Dickens determined to return to Britain under sail. He left New York on June 7 and arrived in Liverpool on June 29. The ship, American packet sailing vessel George Washington, was built at New Bedford, Massachusetts in 1832 and regularly made the trip from New York to Liverpool. In 1845 she was converted to a whaler. In this last chapter of  Charles Dickens and Edgar Allen Poe in Philadelphia

Charles Dickens and Edgar Allen Poe in Philadelphia

It was the ultimate disappointment in a tour that started well in Boston and went downhill from there. "Egypt" or "Little Egypt" is the local nickname for southern Illinois.

It was the ultimate disappointment in a tour that started well in Boston and went downhill from there. "Egypt" or "Little Egypt" is the local nickname for southern Illinois.

Following a Charles Dickens reading in Portland, Maine, on the 30th of March, 1868, 12-year-old Kate Wiggin, having missed the Portland reading, encountered Charles Dickens on a train bound for Boston. Dickens was quite taken with this precocious child and spent considerable time talking with her during the journey. He was amused when she told him that she had read all of his books but added "I do skip some of the very dull parts once in a while; not the short dull parts, but the long ones"

Following a Charles Dickens reading in Portland, Maine, on the 30th of March, 1868, 12-year-old Kate Wiggin, having missed the Portland reading, encountered Charles Dickens on a train bound for Boston. Dickens was quite taken with this precocious child and spent considerable time talking with her during the journey. He was amused when she told him that she had read all of his books but added "I do skip some of the very dull parts once in a while; not the short dull parts, but the long ones"