Charles Dickens on Stage

Explore Charles Dickens' amateur acting and public reading career

Charles Dickens Amateur Theatricals

The story of the Vincent Crummles' traveling theatrical troupe in Nicholas Nickleby was one close to Dickens' heart. As a child Charles was exposed to, and loved, the theater (Johnson, 1952, p. 22-24). As a schoolboy he and his mates amused themselves by putting on plays in a miniature theatre (Johnson, 1952, p. 49).

Had it not been for an illness on the morning of a scheduled audition at the Covent Garden theater in the early 1830s, just before his writing gained attention, he may have made a career on the stage (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 139-140).

After years away from the stage, Dickens agreed to direct and perform in three plays while in Montreal, Canada in 1842 (Johnson, 1952, p. 423-425). The success of the Montreal plays provided the spark that rekindled Dickens' love of the footlights. Back home in London, Dickens gathered friends to perform Ben Jonson's Every Man in his Humour for charity, which was a huge success (Kaplan, 1988, p. 191-193).

These amateur theatricals continued throughout the middle years of Dickens' career as a world famous author. He worked tirelessly as actor and stage manager and, as his friend John Forster remarked, often adjusted scenes, assisted carpenters, invented costumes, devised playbills and generally oversaw the entire production of the performances (Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 436).

Many of his friends and associates in the arts, including Forster, Douglas Jerrold, John Leech, Mark Lemon, Augustus Egg, and Wilkie Collins acted in these theatricals which were performed across Britain. The distinguished actor William Macready, a close friend of Dickens, provided guidance in the performance of the productions (Schlicke, 1999, p. 361). Another friend, artist Clarkson Stanfield, lent a hand designing scenery. The schoolroom in his home, Tavistock House, could be converted to a theater for small performances (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 159). The Dickens' amateur troupe even performed twice for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert (Davis, 1999, p. 4).

This close association with the theater had an important impact on Dickens the author. Theatrical characters abound in the novels and the stories are told in such a visual way that they easily lent themselves to illustrations in the novels, stage dramatizations, and finally, to film.

Later in his career Dickens' theatrical training contributed to the success of his public readings from his works in Britain and America.

1857 - Charles Dickens and The Frozen Deep

In the spring of 1856 Dickens' marriage to Catherine was in the midst of an ugly breakup, and he found himself in need of distraction. This diversion came in the form of a new play, The Frozen Deep. Dickens conveyed his idea for a play based on the Franklin Expedition to Wilkie Collins from Paris where Dickens was busy serializing Little Dorrit in monthly parts (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 761-762).

Scene from The Frozen Deep at Tavistock House

Historical Background

Sir John Franklin made several expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage through the Arctic. His final expedition sailed on May 19, 1845, and was last seen on July 26, 1945, never to be heard from again. There were unsubstantiated rumors that the men in Franklin's party had been driven to cannibalism (Encyclopedia Britannica). There was a general uproar in England at the thought of Englishmen resorting to this "last resource" (Brannon, 1966, p. 14). Dickens argued, in his weekly magazine (Household Words, 1854) against the cannibalism story (Brannon, 1966, p. 14-20).

The Play

Richard Wardour and Frank Aldersley are in love with the same woman. When the woman picks Aldersley, Wardour vows revenge but doesn't know the name of his rival. Both men end up on an expedition to the Arctic. The expedition goes badly and the men are forced to abandon their ships. Wardour learns that Aldersley is the man he seeks. With supplies running low a small band is chosen to try to get to a settlement for help. Both Wardour and Aldersley are chosen as members of this group and it is feared that Wardour will kill Aldersley. In the end, however, Wardour dies saving Aldersley's life for the woman they both love (Johnson, 1952, p. 866).

Sound familiar? It should. Dickens used these same devices, love triangle and self-sacrifice, in his next book A Tale of Two Cities. In fact, Richard Wardour, as, for Dickens, a new kind of flawed hero, would resurface not only as Sydney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities, but as Pip in Great Expectations, and Eugene Wrayburn in Our Mutual Friend (Brannon, 1966, p. 88).

Producing the Play

Dickens acted as manager of the performance and assumed the role of Richard Wardour, Wilkie Collins played Frank Aldersly, and the rest of the cast made up of family and friends. Soon the little schoolroom at Tavistock House was alive with carpenters, painters, gasfitters, and dressmakers, the din reminded Dickens of "the building of Noah's ark." He engaged artists Clarkson Stanfield and William Telbin to paint the backdrops, and recruited Francesco Berger to write music and play piano (Johnson, 1952, p. 866-867).

Later Performances

The performances at Tavistock House earned Dickens rave reviews for his portrayal as Wardour. Many were of the opinion that a professional actor could not have pulled off the performance nearly as well (Slater, 2009, p. 418-419). There originally were no plans to extend the performances past the five January 1857 shows at Tavistock House; however, when Dickens learned of the death of his friend Douglas Jerrold, he resurrected the play to raise money for Jerrold's family. The Queen requested a private performance for the royal family, which took place on July 4, 1857 (Slater, 2009, p. 426-427). When a request for benefit performances of the play be performed at the New Free Trade Hall in Manchester, Dickens at first was doubtful that the play could be staged in such a large hall. In the end, three performances were held at the Manchester hall, using professional actresses in parts formerly played by Dickens' daughters, as it was thought their voices would project better in the large hall (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 786). This decision would impact Dickens for the rest of his life as he fell in love with one of the actresses, Ellen Ternan (Johnson, 1952, p. 910-911).

Charles Dickens Public Readings

Dickens was, first and foremost, an entertainer. From childhood, and into adult life, he loved the stage, and loved and needed the outpouring of adulation he received. He performed in amateur theatricals throughout the 1840s and 50s and, had he not achieved early fame as a writer, would almost certainly have made a career on the stage. Charles Kent, who had seen Dickens' public readings firsthand, observed that he had "an extraordinary degree of dramatic element in his character. It was an integral part of his individuality" (Kent, 1872, p. 7).

-sm.jpg)

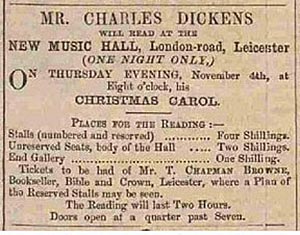

Dickens began giving public readings of his works in 1853, first for charity, and beginning in 1858, for profit. Before this time no great author had performed their works in public, but Dickens' works were uniquely suited for performance, as they would later successfully adapt to the screen (Schlicke, 1999, p. 474-479). Dickens' friend and advisor, John Forster, argued unsuccessfully that such public exhibition for money was beneath his calling as a writer and a gentleman (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 246-247).

See a map and account of Dickens' 1858 reading tour of Britain.

Throughout the 1860s, except for a break at mid-decade when he was writing Our Mutual Friend, Dickens undertook reading tours of Britain, making more money from the readings than he could from writing, even though he always made sure that seats were available at working-class prices (Schlicke, 1999, p. 474-479).

The performances initially included the Christmas books: A Christmas Carol, The Chimes, and Cricket on the Hearth. Later Dickens incorporated scenes from Dombey and Son, Nicholas Nickleby, Pickwick Papers, Martin Chuzzlewit, and his favorite, David Copperfield. He tightened the narrative, wrote stage directions to himself in the margins, and tried to infuse as much humor as possible, leaving out passages of social criticism as inappropriate for evenings of entertainment (Schlicke, 1999, p. 479-480).

Advertisement in the Leicestershire Mercury - 1858

Charles Dickens biographer Edgar Johnson on the public readings: "It was more than a reading; it was an extraordinary exhibition of acting ...without a single prop or bit of costume, by changes of voice, by gesture, by vocal expression, Dickens peopled his stage with a throng of characters" (Johnson, 1952, p. 936).

Thomas Carlyle, author and friend of Dickens, after attending one of the readings, remarked "Charley, you carry a whole company under your own hat" (Johnson, 1952, p. 1009).

After much deliberation, and with the promise of big money, he undertook a reading tour of America from December 1867- April 1868 which earned him just under £20,000 (Slater, 2009, p. 584).

Dickens, in declining health, began a farewell tour of Britain in October 1868, upon his return to England (Dolby, 1887, p. 333-337). This tour included a new, and very passionate, dramatic performance of the murder of Nancy from Oliver Twist. This reading proved controversial for two reasons: that the subject matter would cause mass hysteria among the women present, and that the effort necessary for Dickens to perform the reading successfully would have a detrimental effect on his health. Indeed, many believe that the energy expended in this performance, which he insisted on including even as his health worsened, hastened his premature death on June 9, 1870 (Dolby, 1887, p. 349-352). During the last series of readings, taking place at St. James's Hall in London from January to March, 1870, Dickens' doctor, Frank Beard, attended every reading and had steps installed onto the stage. He gave instruction to Dickens' son Charley, "You must be there every night, and if you see your father falter in the least, you must run and catch him and bring him off to me, or, by Heaven, he'll die before them all" (Johnson, 1952, p. 1144).

Mark Twain saw Dickens perform in January 1868 at the Steinway Hall in New York and gave this report.