Illustrating Charles Dickens

Learn about the original illustrations for Dickens' works

Original Dickens Illustrators:

- Seymour |

- Buss |

- Phiz |

- Cruikshank |

- Cattermole |

- Williams |

- Maclise |

- Leech |

- Stone |

- Fildes |

- Other Original Illustrators

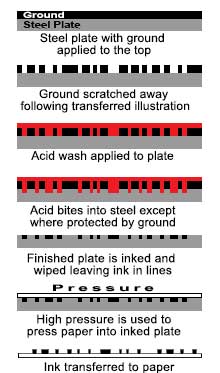

From the original pairing of Charles Dickens with George Cruikshank on Sketches by Boz to his final collaboration with Luke Fildes on The Mystery of Edwin Drood, illustration was an important part of the Dickens experience. In fact only two of Dickens' major works, Hard Times and Great Expectations, were issued originally without illustration. Dickens' works were all issued serially, in monthly or weekly parts. Monthly parts were issued with two illustrations (Davis, 1999, p. 187). The illustrations were usually sketches etched onto steel plates, printed on special paper and bound into the book after an advertisement section and just before the text (Steig, 1978, p. 17-18). In some cases, as in The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge, published in Dickens' weekly magazine Master Humphreys Clock, the illustrations were cut into wood blocks and dropped into the text so that the illustration appeared in the part of the story being illustrated (Steig, 1978, p. 16-17).

Dickens worked in close collaboration with his illustrators, supplying them with an overall summary of the work at the outset for the cover illustration which was printed on heavy colored stock, usually green, which served as a wrapper for each of the monthly parts (Schlicke, 1999, p. 289). Dickens briefed the illustrator on plans for each month's installment so that work on the two illustrations could begin before he wrote them (Steig, 1978, p. 21), and he was not always easy to please (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 28-31).

This close working relationship with his illustrators is important to readers of Dickens today. The illustrations give us a glimpse of the characters as Dickens described them to the illustrator and approved when the drawing was finished. Film makers still use the illustrations as a basis for characterization, costume, and set design in the dramatization of Dickens' works. Indeed, the scenes selected by Dickens to be illustrated provide the reader with what he considered key scenes needing emphasis.

Original illustrators with whom Charles Dickens personally collaborated:

Robert Seymour (1800-1836)

In 1836 publishers Chapman and Hall approached Dickens with the proposal that he write a series of short stories to accompany illustrations by popular artist Robert Seymour. Dickens argued successfully that the stories be the main focus and the illustrations should complement the text. The result of this collaboration was The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Seymour, who had had a nervous breakdown in 1830, illustrated the first two monthly installments with some difficulty satisfying Dickens and his publishers. On the completion of the second installment Seymour committed suicide (Schlicke, 1999, p. 523-525).

In 1836 publishers Chapman and Hall approached Dickens with the proposal that he write a series of short stories to accompany illustrations by popular artist Robert Seymour. Dickens argued successfully that the stories be the main focus and the illustrations should complement the text. The result of this collaboration was The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Seymour, who had had a nervous breakdown in 1830, illustrated the first two monthly installments with some difficulty satisfying Dickens and his publishers. On the completion of the second installment Seymour committed suicide (Schlicke, 1999, p. 523-525).

See a Robert Seymour illustration from The Pickwick Papers

Robert W. Buss (1804-1875)

Buss was hired by Dickens' publishers, Chapman and Hall, when Robert Seymour committed suicide after the 2nd monthly part of Pickwick Papers. Buss did two illustrations for the 3rd monthly part of Pickwick which disappointed the publishers and Buss was dismissed from the project (Johnson, 1952, p. 141). Though disappointed, Buss remained a lifelong Dickens admirer. After Dickens' death Buss produced the famous painting Dickens' Dream of the author surrounded by his characters (Schlicke, 1999, p. 64-65).

Buss was hired by Dickens' publishers, Chapman and Hall, when Robert Seymour committed suicide after the 2nd monthly part of Pickwick Papers. Buss did two illustrations for the 3rd monthly part of Pickwick which disappointed the publishers and Buss was dismissed from the project (Johnson, 1952, p. 141). Though disappointed, Buss remained a lifelong Dickens admirer. After Dickens' death Buss produced the famous painting Dickens' Dream of the author surrounded by his characters (Schlicke, 1999, p. 64-65).

See a Robert W Buss illustration from The Pickwick Papers

Hablot Knight Browne - Phiz (1815-1882)

When Robert Seymour committed suicide after the second installment of The Pickwick Papers the author and his publishers needed a new illustrator. Robert W. Buss was selected but his work proved unsatisfactory. A young William Makepeace Thackeray also applied but the man selected was Hablot Knight Browne who had done some work for Chapman and Hall earlier and had worked with Charles Dickens on a recent pamphlet. Browne and Dickens developed an excellent working relationship and Browne took the nickname Phiz to complement Dickens' Boz. Browne would go on to illustrate Dickens' work for 24 years, ten of Dicken's novels were illustrated by Phiz (Slater, 2009, p. 72).

When Robert Seymour committed suicide after the second installment of The Pickwick Papers the author and his publishers needed a new illustrator. Robert W. Buss was selected but his work proved unsatisfactory. A young William Makepeace Thackeray also applied but the man selected was Hablot Knight Browne who had done some work for Chapman and Hall earlier and had worked with Charles Dickens on a recent pamphlet. Browne and Dickens developed an excellent working relationship and Browne took the nickname Phiz to complement Dickens' Boz. Browne would go on to illustrate Dickens' work for 24 years, ten of Dicken's novels were illustrated by Phiz (Slater, 2009, p. 72).

Browne's comic/satiric style of illustration did not fit well with Dickens' later, more serious, novels and, after the somewhat disappointing illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities, he never worked for Dickens again. Browne was at a loss to understand why he had been dismissed. He speculated "Dickens probably thinks a new hand would give his old puppets a fresh look" (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 941).

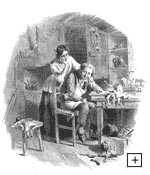

Browne's disappointing illustration for Dombey and Son

Dickens expressed disappointment with an illustration in a letter to his friend John Forster.

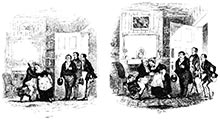

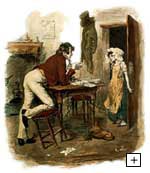

Phiz and Emblematic Detail

In the background of many of the Phiz illustrations of Dickens' novels the illustrator introduces details that help to interpret what is happening in the story. Some of these emblematic details are rather obvious and some are more subtle. Michael Steig, in his book Dickens and Phiz, argues effectively that, although Dickens gave detailed instructions as to the content of the illustrations, many of the emblematic details in the illustrations were added by Phiz on his own. (Steig, 1978, p. 76-78)

Example of emblematic detail in a Phiz illustration

As you read Dickens' novels illustrated by Phiz look for these clues to the story in the incidental items that may seem like background decorations.

Examples of Phiz illustrations:

George Cruikshank (1792-1878)

One of the greatest illustrators of his time, Cruikshank came from a family of artists (Kitton, 1899, p. 1). Charles Dickens met Cruikshank through John Macrone, publisher for successful writer William Harrison Ainsworth, Macrone suggested that Dickens' sketches should be put together in a book, illustrated by Cruikshank. The result was Sketches by Boz published in 1836 (Schlicke, 1999, p. 532).

One of the greatest illustrators of his time, Cruikshank came from a family of artists (Kitton, 1899, p. 1). Charles Dickens met Cruikshank through John Macrone, publisher for successful writer William Harrison Ainsworth, Macrone suggested that Dickens' sketches should be put together in a book, illustrated by Cruikshank. The result was Sketches by Boz published in 1836 (Schlicke, 1999, p. 532).

Cruikshank would later illustrate Dickens' Oliver Twist and was an actor in some of the plays done by Dickens' amateur company. Cruikshank, formerly a prodigious imbiber, would later become a staunch supporter of the temperance movement (Patten, 1992, p. 228-229). After Dickens' death Cruikshank claimed that the plot and many of the characters from Oliver Twist had been his idea, which Dickens' friend and biographer vehemently denied (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 31-32).

Sample George Cruikshank illustrations:

George Cattermole (1800-1868)

Dickens friend and illustrator, collaborating with Browne (Phiz), on Master Humphrey's Clock and the novels The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge. Cattermole's specialty was nostalgic interior and exterior architectural illustration (Schlicke, 1999, p. 68). Thus, his illustrations depict subjects such as the Nell's deathbed (The Old Curiosity Shop) and the Maypole Inn (Barnaby Rudge).

Dickens friend and illustrator, collaborating with Browne (Phiz), on Master Humphrey's Clock and the novels The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge. Cattermole's specialty was nostalgic interior and exterior architectural illustration (Schlicke, 1999, p. 68). Thus, his illustrations depict subjects such as the Nell's deathbed (The Old Curiosity Shop) and the Maypole Inn (Barnaby Rudge).

Sample George Cattermole illustrations:

Daniel Maclise (1807-1870)

Artist and close friend of Dickens early in his career. He painted several portraits of the Dickens family including the famous Nickleby Portrait, painted in 1839, and used as the frontispiece for Nicholas Nickleby (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 287-288). Maclise provided illustrations for The Old Curiosity Shop and several of the Christmas books: The Chimes, Cricket on the Hearth, and The Battle of Life.

Artist and close friend of Dickens early in his career. He painted several portraits of the Dickens family including the famous Nickleby Portrait, painted in 1839, and used as the frontispiece for Nicholas Nickleby (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 287-288). Maclise provided illustrations for The Old Curiosity Shop and several of the Christmas books: The Chimes, Cricket on the Hearth, and The Battle of Life.

Sample Daniel Maclise illustrations:

John Leech (1817-1864)

Cartoonist and illustrator famous for his work for Punch. Leech was one of the artists put forward to replace Robert Seymour for The Pickwick Papers and although not selected Leech and Dickens became lifelong friends. Leech contributed many illustrations for Dickens' Christmas books and was sole illustrator for A Christmas Carol. He was, along with George Cruikshank and Frank Stone, one of the actors in the amateur plays put on by Dickens' circle of friends (Schlicke, 1999, p. 322-325).

Cartoonist and illustrator famous for his work for Punch. Leech was one of the artists put forward to replace Robert Seymour for The Pickwick Papers and although not selected Leech and Dickens became lifelong friends. Leech contributed many illustrations for Dickens' Christmas books and was sole illustrator for A Christmas Carol. He was, along with George Cruikshank and Frank Stone, one of the actors in the amateur plays put on by Dickens' circle of friends (Schlicke, 1999, p. 322-325).

Sample John Leech illustrations:

Frank Stone (1800-1859)

Dickens' close friend Frank Stone was a painter, illustrator, and neighbor of the Dickens family from 1851 to 1860. Stone contributed illustrations to Dickens' Christmas book The Haunted Man, and later editions of Nicholas Nickleby and Martin Chuzzlewit. He was also an actor in Dickens' amateur theatricals (Davis, 1999, p. 367).

Dickens' close friend Frank Stone was a painter, illustrator, and neighbor of the Dickens family from 1851 to 1860. Stone contributed illustrations to Dickens' Christmas book The Haunted Man, and later editions of Nicholas Nickleby and Martin Chuzzlewit. He was also an actor in Dickens' amateur theatricals (Davis, 1999, p. 367).

See a Frank Stone illustration from The Haunted Man

Marcus Stone (1840-1921)

When Frank Stone died in 1859 Dickens recommended his son Marcus to his publishers. Marcus illustrated Great Expectations and Our Mutual Friend. Stone's figures are more realistic and less caricature than his predecessors. Marcus later gave up book illustration and became an accomplished painter (Schlicke, 1999, p. 540).

Sample Marcus Stone illustrations:

Luke Fildes (1844-1927)

With Marcus Stone's decision to quit illustration in favor of painting and Dickens' dissatisfaction with the recent work of Hablot Browne, a new illustrator was needed for The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Originally Charles Collins, brother of Dickens' friend Wilkie Collins and husband to Dickens' daughter Kate, was hired. After designing the cover he gave up the project citing ill health. Dickens interviewed and hired Luke Fildes, a young artist who had studied at the Royal Academy. Using the existing cover design and close collaboration with Dickens, Fildes had completed six illustrations when Dickens died halfway through the monthly parts. Fildes later completed six more illustrations to accompany the release of the remaining three monthly parts published posthumously. Fildes remained close to the Dickens family and was pursued to the end of his life for clues as to the ending of Dickens' unfinished novel (Schlicke, 1999, p. 233).

With Marcus Stone's decision to quit illustration in favor of painting and Dickens' dissatisfaction with the recent work of Hablot Browne, a new illustrator was needed for The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Originally Charles Collins, brother of Dickens' friend Wilkie Collins and husband to Dickens' daughter Kate, was hired. After designing the cover he gave up the project citing ill health. Dickens interviewed and hired Luke Fildes, a young artist who had studied at the Royal Academy. Using the existing cover design and close collaboration with Dickens, Fildes had completed six illustrations when Dickens died halfway through the monthly parts. Fildes later completed six more illustrations to accompany the release of the remaining three monthly parts published posthumously. Fildes remained close to the Dickens family and was pursued to the end of his life for clues as to the ending of Dickens' unfinished novel (Schlicke, 1999, p. 233).

Sample Luke Fildes illustrations:

Other Original Illustrators of Dickens

Samuel Williams (1788-1853)Williams was a skilled wood engraver who had cut several blocks for Master Humphrey's Clock. When Hablot Browne and George Cattermole were both unavailable to draw a needed illustration for The Old Curiosity Shop, Dickens asked Williams to draw Nell's bed in the curiosity shop. Dickens was reportedly pleased with the result but Williams never did another illustration for Dickens (Schlicke, 1999, p. 587).

Richard Doyle (1824-1883) With the exception of John Leech, Doyle prepared more illustrations for Dickens' Christmas books than anyone, contributing illustrations for The Battle of Life, The Cricket on the Hearth, and The Chimes. There is no evidence that Doyle and Dickens ever met, the instructions for the illustrations coming from the publishers (Kitton, 1899, p. 149-152).

Clarkson Stanfield (1793-1867) The famous land/seascape painter did illustrations for the Christmas books The Battle of Life, The Chimes and The Haunted Man. Stanfield agreed to do illustrations for Pictures from Italy but later withdrew claiming the book contained an anti-Catholic bias (Davis, 1999, p. 364-365).

Samuel Palmer (1805-1881) British landscape painter, etcher and printmaker. Palmer did four illustrations for Pictures from Italy after Clarkson Stanfield backed out for religious reasons (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 491-492).

Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) Painter and sculptor famous for paintings of animals and for the lions on Nelson's monument in Trafalgar Square. Landseer did an illustration for the Christmas book The Cricket on the Hearth (Davis, 1999, p. 203).

John Tenniel (1820-1914) Punch illustrator who also did the illustrations for Lewis Carroll's Alice books. Tenniel did illustrations for the Christmas book The Haunted Man (Davis, 1999, p. 384).

Illustration Links:

19th Century Illustration

A good source of information on illustration printing techniques in the 19th century is available from The Victorian Web

Victorian Publishing

The British Museum's online exhibition:

Aspects of the Victorian Book includes information on book illustration in the 19th century.

The publication of illustrations in the nineteenth century was a laborious and time-consuming process. The two primary methods of graphic reproduction used in the publication of illustrations for Dickens' works were etching and wood engraving.

The publication of illustrations in the nineteenth century was a laborious and time-consuming process. The two primary methods of graphic reproduction used in the publication of illustrations for Dickens' works were etching and wood engraving.