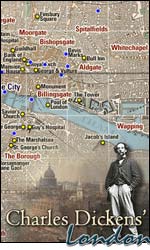

Charles Dickens London

What was it like to live in the London of Charles Dickens?

Charles Dickens applied his unique power of observation to the city in which he spent most of his life. He routinely walked the city streets, 10 or 20 miles at a time, and his descriptions of nineteenth century London allow readers to experience the sights, sounds, and smells of the old city.

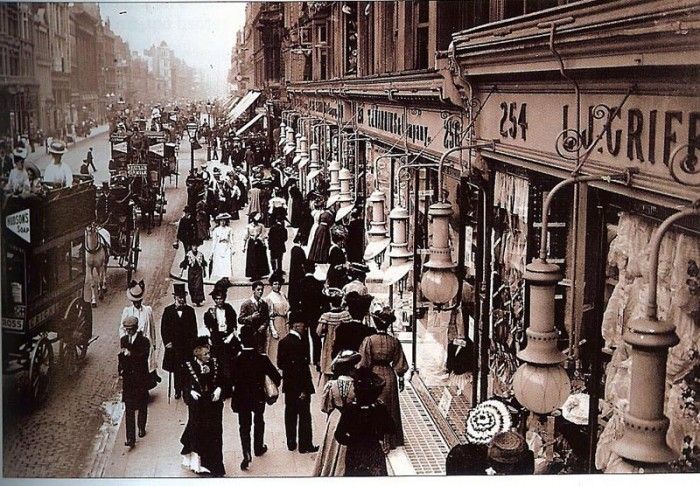

This ability to immerse the reader into time and place sets the perfect stage for Dickens to weave his fiction.Victorian London was the largest, most spectacular city in the world. While Britain was experiencing the Industrial Revolution, its capital was both reaping the benefits and suffering the consequences. In 1800 the population of Greater London was around a million souls. That number would swell to 6.5 million by 1900 (Weinreb, 2008, p. 657). While fashionable areas like Regent and Oxford streets were growing in the west, new docks supporting the city's place as the world's trade center were being built in the east. Perhaps the biggest impact on the expansion of London was the coming of the railroad in the 1830s which displaced thousands and shifted population away from the City and into the suburbs (Porter, 1994, p. 209).

The price of this explosive growth and domination of world trade was untold squalor and filth. In his excellent biography, Dickens, Peter Ackroyd notes that "If a late twentieth-century person were suddenly to find himself in a tavern or house of the period, he would be literally sick - sick with the smells, sick with the food, sick with the atmosphere around him" (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 10).

Imagine yourself in the London of the early 19th century. The homes of the upper and middle class exist in close proximity to areas of unbelievable poverty and filth. Rich and poor alike are thrown together in the crowded city streets. Street sweepers attempt to keep the streets clean of manure, the result of thousands of horse-drawn vehicles. The city's thousands of chimney pots are belching coal smoke, resulting in soot which seems to settle everywhere. In many parts of the city raw sewage flows in gutters that empty into the Thames. Street vendors hawking their wares add to the cacophony of street noises. Pick-pockets, prostitutes, drunks, beggars, and vagabonds of every description add to the colorful multitude.

Personal cleanliness is not a big priority, nor is clean laundry. In close, crowded rooms the smell of unwashed bodies is stifling.

It is unbearably hot by the fire, numbingly cold away from it.At night the major streets are lit with feeble gas lamps. Side and secondary streets may not be lit at all and link boys are hired to guide the traveler to his destination. Inside, a candle or oil lamp struggles against the darkness and blacken the ceilings.

In Little Dorrit Dickens describes a London rain storm:

In the country, the rain would have developed a thousand fresh scents, and every drop would have had its bright association with some beautiful form of growth or life. In the city, it developed only foul stale smells, and was a sickly, lukewarm, dirt-stained, wretched addition to the gutters (Little Dorrit, p. 30-31).

In the Streets

This film (credit BFI) made 33 years after Dickens' death still gives a good idea of what the London streets of Dickens' times would look like.

After the Stage Carriages Act of 1832 the hackney cab was gradually replaced by the omnibus as a means of moving about the city. By 1900, 3000 horse-drawn buses were carrying 500 million passengers a year (Porter, 1994, p. 225). A traffic count in Cheapside and London Bridge in 1850 showed a thousand vehicles an hour passing through these areas during the day (Welsh, 1971, p. 21). All of this added up to an incredible amount of manure which had to be removed from the streets. In wet weather straw was scattered in walkways, storefronts, and in carriages to try to soak up the mud and wet.

Cattle were driven through the London streets to the market at Smithfield until the market was moved to Islington in 1855 (Porter, 1994, p. 193-194). In an article for Household Words in March 1851 Dickens, with characteristic sarcasm, describes the environmental impact of having live cattle markets and slaughterhouses in the city:

"In half a quarter of a mile's length of Whitechapel, at one time, there shall be six hundred newly slaughtered oxen hanging up, and seven hundred sheep but, the more the merrier proof of prosperity. Hard by Snow Hill and Warwick Lane, you shall see the little children, inured to sights of brutality from their birth, trotting along the alleys, mingled with troops of horribly busy pigs, up to their ankles in blood but it makes the young rascals hardy. Into the imperfect sewers of this overgrown city, you shall have the immense mass of corruption, engendered by these practices, lazily thrown out of sight, to rise, in poisonous gases, into your house at night, when your sleeping children will most readily absorb them, and to find its languid way, at last, into the river that you drink" (Household Words, 1851, v. II, p. 554).

In Oliver Twist, Dickens describes the scene as Oliver and Bill Sikes travel through the Smithfield live-cattle market on their way to burglarize the Maylie home: "It was market-morning. The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire; a thick steam, perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle, and mingling with the fog, which seemed to rest upon the chimney-tops, hung heavily above. All the pens in the centre of the large area, and as many temporary pens as could be crowded into the vacant space, were filled with sheep; tied up to posts by the gutter side were long lines of beasts and oxen, three or four deep. Countrymen, butchers, drovers, hawkers, boys, thieves, idlers, and vagabonds of every low grade, were mingled together in a mass; the whistling of drovers, the barking dogs, the bellowing and plunging of the oxen, the bleating of sheep, the grunting and squeaking of pigs, the cries of hawkers, the shouts, oaths, and quarrelling on all sides; the ringing of bells and roar of voices, that issued from every public-house; the crowding, pushing, driving, beating, whooping and yelling; the hideous and discordant dim that resounded from every corner of the market; and the unwashed, unshaven, squalid, and dirty figures constantly running to and fro, and bursting in and out of the throng; rendered it a stunning and bewildering scene, which quite confounded the senses" (Oliver Twist, p. 153).

Henry Mayhew estimated that in the 1850s there were 12,000 costermongers (street sellers) making their living in the London streets. These sellers sold fruits, vegetables, flowers, fish, pies, muffins, and a variety of other goods. Generally the costers would go out early in the morning and buy their goods from the London markets such as Billingsgate fish market, Covent Garden, or Borough Market, bartering for the cheapest price with what they called their "stock money". These goods were then pushed through the streets in rented barrows. Mayhew detailed the lives of these street sellers in his London Labour and the London Poor (1851). Read Mayhew's description of Covent Garden Market.

The River Thames

The River Thames was always the lifeblood of London. Since the time of the Romans, Londoners had been making their living from the river, either directly on the water or from the warehouses and counting houses of the City that sprang up because of the commerce supplied by the Thames (Porter, 1994, p. 14-15).

The Romans built the first bridge over the Thames, a stucture of wood, near the site of present-day London Bridge (Ackroyd, 2000, p. 22). A succession of wooden bridges were finally replaced by a stone bridge in 1176 (Weinreb, 2008, p. 496). These were the only passage over the river in London until 1750 when Westminster Bridge was completed (Ackroyd, 2000, p. 511).The part of the river below London Bridge, the furthest point navigable by large ships, is called the Pool of London, and in the 1800s this area was a forest of masts as ships from all over the world called at the London Docks, a testimony to the predominance of British commerce (Leapman, 1989, p. 27).

Just as the river runs through London, so it runs through the novels of Dickens. The river becomes a major player in many of the novels. In Great Expectations, Pip practices his boating ability in preparation for smuggling Magwitch out of the country via the Thames leading to the climactic struggle on the water. Dickens’ last completed novel, Our Mutual Friend, is centered on Thames watermen who make their living searching the river for the bodies of the drowned.

While the river provides commerce and wealth, it also brings death and disease. Jumping from one of London’s bridges was a popular method of suicide as Dickens describes in Down with the Tide. In Little Dorrit Dickens describes the Thames as a "deadly sewer" (Little Dorrit, p. 28), a harbinger of death and disease.

Cholera

Until the second half of the 19th century London residents were drinking from the very same parts of the Thames that the open sewers were discharging into. Until 1854 it was widely thought that disease was spread through foul air or miasma. It seemed obvious to the Victorians, even the learned ones, that if it stinks, it must be causing disease (Johnson, 2006, p. 68-72).

When Cholera broke out in the Soho area in 1854 Dr John Snow teamed with Rev. Henry Whitehead to prove that the disease was spread not through foul odors and bad air, but by contaminated water. Cholera is spread simply by one human digesting the bacteria in the excrement of other infected humans (Johnson, 2006, p. 39). Snow and Whitehead solved this riddle not by direct study of the bacteria, but by spatially projecting pedestrian patterns of where residents got their drinking water.

By this method they were able to show that all the Cholera victims in the area drank from the same Broad Street pump. The well had been contaminated with raw sewage coming from the homes of Cholera sufferers. The pump handle was removed, and the epidemic ended (Johnson, 2006, p. 160). Read more about this fascinating story in Steven Johnson's The Ghost Map.Meanwhile, the Thames continued to be little more than a sewer running through the city. Only after "The Great Stink of 1858", when the stench of the river caused Parliament to recess, did the city take action (Halliday, 1999, p. xi). Sir Joseph Bazalgette, chief engineer of the new Metropolitan Board of Works, put into effect a plan that finally provided London with adequate sewers as part of the Victoria Embankment project completed in 1875 (Leapman, 1989, p. 302).

The Law

The London Watch was the primary means of keeping the peace from medieval times. In the 1750s, Henry Fielding established the Bow Street Runners as a more effective means of law enforcement. In 1829 London's first organized and centralized police force was created by Home Secretary, Sir Robert Peel (hence the name Peelers and, eventually, Bobbies), with headquarters in what would become known as Scotland Yard (Ackroyd, 2000, p. 277-281).

The Poor

The Victorian answer to dealing with the poor and indigent was the New Poor Law, enacted in 1834. Previously it had been the burden of the parishes to take care of the poor.

The new law required parishes to band together and create regional workhouses where aid could be applied for. The workhouse was little more than a prison for the poor. Civil liberties were denied, families were separated, and human dignity was destroyed. The true poor often went to great lengths to avoid this relief (Davis, 1999, p. 322-323).Charles Dickens, because of the childhood trauma caused by his father's imprisonment for debt and his consignment to Warren's Blacking Factory to help support his family, was a true champion to the poor. He repeatedly pointed out the atrocities of the system through his novels, notably in Oliver Twist, and through Betty Higden in Our Mutual Friend.

Journalist Henry Mayhew chronicled the plight of the London poor in articles originally written for the Morning Chronicle and later collected in London Labour and the London Poor (1851).

End of an Era

With the turn of the century and Queen Victoria's death in 1901 the Victorian period came to a close. Many of the ills of the 19th century were remedied through education, technology and social reform... and by the social consciousness raised by the immensely popular novels of Charles Dickens.

Eating and Drinking with Charles Dickens

Throughout his work Charles Dickens relishes in the description of food and drink in such a way as to make the most meager meal seem a feast. From Pip and Joe comparing slices of bread in Great Expectations (Great Expectations, p. 8-9), to the Ghost of Christmas Present's magnificent spread (Christmas Books-A Christmas Carol, p. 39), Dickens celebrates the culinary delights of his day. There is much roast fowl and joint of mutton, plum pudding and boiled beef.

Drinking is ubiquitous in Dickens. From the peasants in Paris soaking up the spilled wine in the street in A Tale of Two Cities (A Tale of Two Cities, p. 27), to Mr Micawber's famous punch (David Copperfield, p. 412), everyone seems to have a drink in their hand. This partly reflects the fact that, in Dickens' London, alcohol was safer to drink than the water (Pool, 1993, p. 210).

Charles Dickens, by all indications, was a moderate drinker himself (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 248). While diligently pointing out the evils of overindulgence, he also had no patience with the Temperance Movement, which he lampooned in Pickwick Papers. Indeed Dickens had a falling out with his friend and illustrator George Cruikshank when Cruikshank, formerly a heavy drinker, became a zealous supporter of abstinence (Patten, 1992, p. 228-229).

In reply to a letter from an irate advocate of abstinence in 1847 Dickens answered:

"I have no doubt whatever that the warm stuff in the jug at Bob Cratchit's Christmas dinner, had a very pleasant effect on the simple party. I am certain that if I had been at Mr. Fezziwig's ball, I should have taken a little negus -- and possibly not a little beer -- and been none the worse for it, in heart or head. I am very sure that the working people of this country have not too many household enjoyments, and I could not, in my fancy or in actual deed, deprive them of this one when it is so innocently shared" (Hartley, 2012, p. 182).

Demoralisation and Total Abstinence

An article written by Dickens and printed in the Examiner on October 27, 1849, rebuking a call for total abstinence to combat drunkeness.

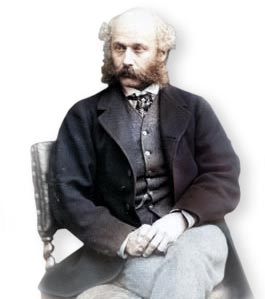

Ever wonder why the subjects of all those portraits taken in the early days of photography sport such grim expressions? It had more to do with the limits of the technology than of the somber nature of the subject. Smiles are more spontaneous, and harder to hold naturally for the long exposure times required by the photographic equipment of the day.

Ever wonder why the subjects of all those portraits taken in the early days of photography sport such grim expressions? It had more to do with the limits of the technology than of the somber nature of the subject. Smiles are more spontaneous, and harder to hold naturally for the long exposure times required by the photographic equipment of the day.

Dickens' genius was thrust upon the world stage at a time of intense change in London and probably none more dramatic than that of the coming of the railroad. This change can be seen in the progress of Dickens' novels.

Dickens' genius was thrust upon the world stage at a time of intense change in London and probably none more dramatic than that of the coming of the railroad. This change can be seen in the progress of Dickens' novels.